Smart Reading

Chapter Opener

20

read closely

Smart Reading

There’s probably no better strategy for generating ideas than reading. Reading can deepen your impressions of any subject you are exploring, provide necessary background information, sharpen your critical acumen, and introduce you to alternative views. Reading also places you within a community of writers who have already thought about a subject.

Of course, not all reading serves the same purposes.

You check out a dozen scholarly books to do research for a paper and then look for journal articles online.

You check out a dozen scholarly books to do research for a paper and then look for journal articles online. You consult stock market quotes and baseball box scores because you want numbers now.

You consult stock market quotes and baseball box scores because you want numbers now. You interpret an organization chart to figure out who actually controls the student government budget.

You interpret an organization chart to figure out who actually controls the student government budget. You read an old diary to discover what life was like before photocopiers, air-

You read an old diary to discover what life was like before photocopiers, air-conditioning, and ( gulp!) smartphones.  You pack a Divergent series novel for pleasure reading on the Jersey Shore.

You pack a Divergent series novel for pleasure reading on the Jersey Shore.

READ is registered trademark of the American Library Association. Image courtesy of ALA Graphics, alastore.ala.org. Used with permission from the American Library Association, www.ala.org.

Yet any of these reading experiences, as well as thousands of others, might lead to ideas for projects.

You’ve probably been thoroughly schooled in basic techniques of academic reading: Survey the table of contents, preread to get a sense of the whole, look up terms or concepts you don’t know, summarize what you’ve read, and so on. Such suggestions are practical, especially for difficult scholarly or professional texts. The following advice about reading can help you sharpen your college-

For a tutorial on active reading, see Tutorials > Critical Reading > Active Reading Strategies

For a tutorial on active reading, see Tutorials > Critical Reading > Active Reading Strategies

Read to deepen what you already know. Whatever your interests or experiences in life, you’re not alone. Others have explored similar paths and have probably written about them. Reading their work may give you the confidence to bring your own thoughts to public attention. Whether your passion is tintype photography, skateboarding, or film fashions of the 1930s, you’ll find excellent books on the subject by browsing library catalogs or checking online bookstores.

For example, if you have worked at a fast-

If you don't have the time to read, you don't have the time or tools to write.

— Stephen King

© Dick Dickinson.

Read above your level of knowledge. It’s easy to connect with people online who share your interests, but they often don’t know much more about a topic than you do. To find fresh ideas, push your reading to a more demanding level. Spend time with experts whose books and articles you can’t blow right through. You’ll know you are there when you find yourself looking up names, adding terms to your vocabulary, and feeling humbled by what you still need to learn about a subject. That’s when invention occurs and ideas germinate.

Read what makes you uncomfortable. Most of us today have access to devices that connect us to endless sources of information. But all those voices also mean that we can choose to read (or watch) only materials that confirm our existing beliefs and prejudices — and many people do. Such narrowness will be exposed, however, whenever you write on a controversial subject and find readers arguing back with facts you never considered before. Surprise! The world is more complicated than you thought. The solution is simple: Get out of the echo chamber and read more broadly, engaging with those who see the world differently.

Read against the grain. Skeptics and naysayers may be no fun at parties, but their habits may be worth emulating whenever you are reading. It makes sense to read with an open mind, giving reputable writers and their ideas a fair hearing. But you always want to raise questions about the assumptions writers make, the logic they use, the evidence they present, and the authorities and sources upon which they build their arguments.

Reading against the grain does not mean finding fault with everything, but rather letting nothing slip by without scrutiny. Treat the world around you as a text to be read and analyzed. (think critically) Ask questions. Why do so few men take liberal-

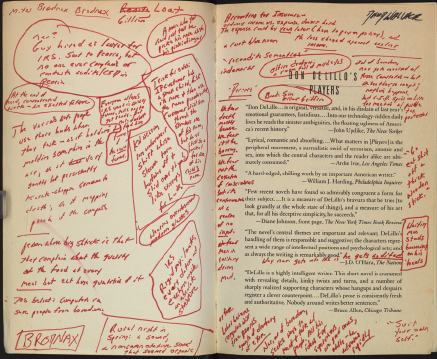

The late writer David Foster Wallace took copious notes when he read — in this case, the Don DeLillo novel Players.

PLAYERS by Don DeLillo. Copyright © 1977 by Don DeLillo. Used by permission of the Wallace Literary Agency, Inc. David Foster Wallace notes used by permission of the David Foster Wallace Literary Trust and the Harry Ransom Center, The University of Texas at Austin.

Read slowly. Browsing online has made many of us superficial readers. For serious texts, forget speed-

Annotate what you read. Find some way to record your reactions to whatever you read. If you own the text and don’t mind marking it, use highlighting pens to flag key ideas. Then converse with them and leave a record. Electronic media and e-

For an activity on critical reading, see Tutorials > LearningCurve Activities > Critical Reading

For an activity on critical reading, see Tutorials > LearningCurve Activities > Critical Reading