Critical Thinking

Chapter Opener

21

think critically/ avoid fallacies

Critical Thinking

We all get edgy when our written work is criticized (or even edited) because the ideas we put on a page emerge from our own thinking —writing is us. Granted, our words rarely express exactly who we are or what we’ve been imagining, but such distinctions get lost when someone points to our work and says, “That’s stupid” or “What crap!” The criticism cuts deep; it feels personal.

Fortunately, there’s a way to avoid embarrassing gaffes in your work: critical thinking, a term that describes mental habits that reinforce logical reasoning and analysis. There are lots of ways to develop good sense, from following the strategies of smart reading described in Chapter 20 to using the rhetorical tactics presented throughout the “Guide” section of this book.

Here we focus on specific dimensions of critical thinking that you will find useful in college writing.

Think in terms of claims and reasons. Whenever you read reports, arguments, or analyses, chances are you begin by identifying the claims writers make and assessing the evidence that supports them. Logically, then, when you write in these genres, you should expect the same scrutiny.

Claims are the passages in a text where you make an assertion, offer an argument, or present a hypothesis for which you intend to provide evidence.

Using a cell phone while driving is dangerous.

Playing video games can improve intelligence.

Worrying about childhood obesity is futile.

Claims may occur almost anywhere in a paper: in a thesis statement, in the topic sentences of paragraphs, in transitional passages, or in summaries or conclusions. (An exception may be formal scientific writing, in which the hypothesis, results, and discussion will occur in specific sections of an article.)

Make sure that all your major claims in a paper are accompanied by plausible supporting reasons either in the same sentence or in adjoining material. Such reasons are usually introduced by expressions as straightforward as because, if, to, and so. Once you attach reasons to a claim, you have made a deeper commitment to it. You must then do the hard work of providing readers with convincing evidence, logic, or conditions for accepting your claim. Seeing your ideas fully stated on paper early in a project may even persuade you to abandon an implausible claim — one you cannot or do not want to defend.

Using a cell phone while driving is dangerous since distractions are a proven cause of auto accidents.

Playing video games can improve intelligence if they teach young gamers to make logical decisions quickly.

Worrying about childhood obesity is futile because there's nothing we can do about it.

Think in terms of premises and assumptions. Probe beneath the surface of key claims and reasons that writers offer, and you will discover their core principles, usually only implied but sometimes stated directly: These are called premises or assumptions. In oral arguments, when people say I get where you’re coming from, they signal that they understand your assumptions. You want to achieve similar clarity, especially whenever the claims you make in a report or argument are likely to be controversial or argumentative. Your assumptions can be general or specific, conventional or highly controversial, as in the following examples.

Improving human safety and well-

We should discourage behaviors that contribute to traffic accidents. [specific]

Improving intelligence is desirable. [conventional]

Play should train children to think quickly. [controversial]

When writing for readers who mostly share your values, you usually don’t have to explain where you’re coming from. But be prepared to explain your values to more general or hostile readers: This is what I believe and why. Naturally — and here’s where the critical thinking comes in — you yourself need to understand the assumptions upon which your claims rest. Are they logical? Are they consistent? Are you prepared to stand by them? Or is it time to rethink some of your principles?

Think in terms of evidence. A claim without evidence attached is just that — a barefaced assertion no better than a child’s “Oh, yeah?” So you should choose supporting material carefully, always weighing whether it is sufficient, complete, reliable, and unbiased. (refine your search) Has an author you want to cite done solid research? Or does the evidence provided seem flimsy or anecdotal? Can you offer enough evidence yourself to make a convincing case — or are you cherry-

Anticipate objections. Critical thinkers understand that serious issues have many dimensions — and rarely just two sides. That’s because they have done their homework, which means trying to understand even those positions with which they strongly disagree. When you start writing with this kind of inclusive perspective, you’ll hear voices of the loyal opposition in your head and you’ll be able to address objections even before potential readers make them. At a minimum, you will enhance your credibility. But more important, you’ll have done the kind of thinking that makes you smarter.

Avoid logical fallacies. Honest, fair-

One way to enhance your reputation as a writer and critical thinker is to avoid logical fallacies. Fallacies are rhetorical moves that corrupt solid reasoning — the verbal equivalent of sleight of hand. The following classic, but all too common, fallacies can undermine the integrity of your writing.

Appeals to false authority. Be sure that any experts or authorities you cite on a topic have real credentials in the field and that their claims can be verified. Similarly, don’t claim or imply knowledge, authority, or credentials yourself that you don’t have. Be frank about your level of expertise. Framing yourself as an honest, if amateur, broker on a subject can even raise your credibility.

Appeals to false authority. Be sure that any experts or authorities you cite on a topic have real credentials in the field and that their claims can be verified. Similarly, don’t claim or imply knowledge, authority, or credentials yourself that you don’t have. Be frank about your level of expertise. Framing yourself as an honest, if amateur, broker on a subject can even raise your credibility. Ad hominem attacks. In arguments of all kinds, you may be tempted to bolster your position by attacking the personal integrity of your opponents when character really isn’t an issue. It’s easy to resort to name-

Ad hominem attacks. In arguments of all kinds, you may be tempted to bolster your position by attacking the personal integrity of your opponents when character really isn’t an issue. It’s easy to resort to name-calling (socialist, racist) or character assassination, but it usually signals that your own case is weak.  Dogmatism. Writers fall back on dogmatism whenever they want to give the impression, usually false, that they control the party line on an issue and have all the right answers. You are probably indulging in dogmatism when you begin a paragraph, No serious person would disagree or How can anyone argue . . .

Dogmatism. Writers fall back on dogmatism whenever they want to give the impression, usually false, that they control the party line on an issue and have all the right answers. You are probably indulging in dogmatism when you begin a paragraph, No serious person would disagree or How can anyone argue . . .

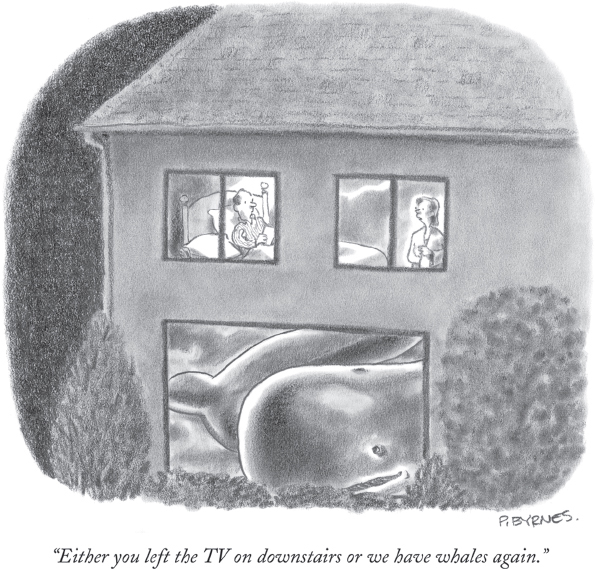

Either/or choices. A shortcut to winning arguments, which even Socrates abused, is to reduce complex situations to simplistic choices: good/bad, right/wrong, liberty/tyranny, smart/dumb, and so on. If you find yourself inclined to use some version of the either/or strategy, think again. Capable readers see right through this tactic and demolish it simply by pointing to alternatives that haven’t been considered.

Either/or choices. A shortcut to winning arguments, which even Socrates abused, is to reduce complex situations to simplistic choices: good/bad, right/wrong, liberty/tyranny, smart/dumb, and so on. If you find yourself inclined to use some version of the either/or strategy, think again. Capable readers see right through this tactic and demolish it simply by pointing to alternatives that haven’t been considered. Scare tactics. Avoid them. Arguments that make their appeals by preying on the fears of audiences are automatically suspect. Targets may be as vague as “unforeseen consequences” or as specific as particular organizations or groups of people who pose various threats. When such fears may be legitimate, make sure you provide evidence for the danger and don’t overstate it.

Scare tactics. Avoid them. Arguments that make their appeals by preying on the fears of audiences are automatically suspect. Targets may be as vague as “unforeseen consequences” or as specific as particular organizations or groups of people who pose various threats. When such fears may be legitimate, make sure you provide evidence for the danger and don’t overstate it. Sentimental or emotional appeals. Maybe it’s fine for the Humane Society to decorate its pleas for cash with pictures of sad puppies, but you can see how the tactic might be abused. In your own work, be wary of using language that pushes buttons the same way, oohing and aahing readers out of their best judgment.

Sentimental or emotional appeals. Maybe it’s fine for the Humane Society to decorate its pleas for cash with pictures of sad puppies, but you can see how the tactic might be abused. In your own work, be wary of using language that pushes buttons the same way, oohing and aahing readers out of their best judgment.

© Pat Byrnes/The New Yorker/Condé Nast.

Hasty or sweeping generalizations. Drawing conclusions from too little evidence or too few examples is a hasty generalization (Climate change must be a fraud because we sure froze last winter); making a claim apply too broadly is a sweeping generalization (All Texans love pickups). Competent writers avoid the temptation to draw conclusions that fit their preconceived notions — or pander to those of an intended audience. But the temptation is powerful, so you might find examples, even in college reading assignments.

Hasty or sweeping generalizations. Drawing conclusions from too little evidence or too few examples is a hasty generalization (Climate change must be a fraud because we sure froze last winter); making a claim apply too broadly is a sweeping generalization (All Texans love pickups). Competent writers avoid the temptation to draw conclusions that fit their preconceived notions — or pander to those of an intended audience. But the temptation is powerful, so you might find examples, even in college reading assignments. Faulty causality. Just because two events or phenomena occur close together in time doesn’t mean that one caused the other. (The Red Sox didn’t start winning because you put on the lucky boxers.) People are fond of leaping to such easy conclusions, and many pundits and politicians do routinely exploit this weakness, particularly in situations involving economics, science, health, crime, and culture. Causal relationships are almost always complicated, and you will get credit for dealing with them honestly. (understand causal analyses)

Faulty causality. Just because two events or phenomena occur close together in time doesn’t mean that one caused the other. (The Red Sox didn’t start winning because you put on the lucky boxers.) People are fond of leaping to such easy conclusions, and many pundits and politicians do routinely exploit this weakness, particularly in situations involving economics, science, health, crime, and culture. Causal relationships are almost always complicated, and you will get credit for dealing with them honestly. (understand causal analyses)

Evasions, misstatements, and equivocations. Evasions are utterances that avoid the truth, misstatements are untruths excused as mistakes, and equivocations are lies made to seem like truths. Skilled readers know when a writer is using these slippery devices, so avoid them.

Evasions, misstatements, and equivocations. Evasions are utterances that avoid the truth, misstatements are untruths excused as mistakes, and equivocations are lies made to seem like truths. Skilled readers know when a writer is using these slippery devices, so avoid them. Straw men. Straw men are easy or habitual targets that writers aim at to win an argument. Often the issue in such an attack has long been defused or discredited: for example, middle-

Straw men. Straw men are easy or habitual targets that writers aim at to win an argument. Often the issue in such an attack has long been defused or discredited: for example, middle-class families abusing food stamps, immigrants taking jobs from hardworking citizens, the rich not paying a fair share of taxes. When you resort to straw- man arguments, you signal to your readers that you may not have much else in your arsenal.  Slippery-

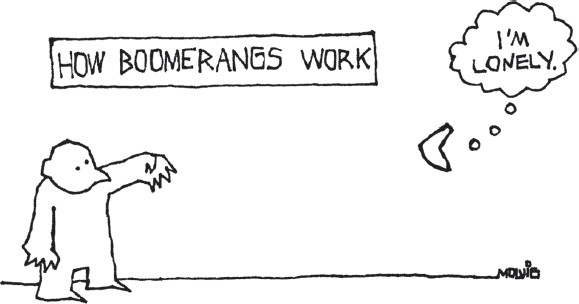

Slippery-slope arguments. Take one wrong step off the righteous path and you’ll slide all the way down the hill: That’s the warning that slippery-slope arguments make. They aren’t always inaccurate, but they are easy to overstate. Will using plastic bags really doom the planet? Maybe or maybe not. If you create a causal chain, be sure that you offer adequate support for every step and don’t push beyond what’s plausible.  Bandwagon appeals. You haven’t made an argument when you simply tell people it’s time to cease debate and get with popular opinion. Too many bad decisions and policies get enacted that way. If you order readers to jump aboard a bandwagon, expect them to resist.

Bandwagon appeals. You haven’t made an argument when you simply tell people it’s time to cease debate and get with popular opinion. Too many bad decisions and policies get enacted that way. If you order readers to jump aboard a bandwagon, expect them to resist. Faulty analogies. Similes and analogies are worth applauding when they illuminate ideas or make them comprehensible or memorable. But seriously analyze the implications of any analogies you use. Calling a military action either “another Vietnam” or a “crusade” might raise serious issues, as does comparing one’s opponents to “Commies” or the KKK. Readers have a right to be skeptical of writers who use such ploys.

Faulty analogies. Similes and analogies are worth applauding when they illuminate ideas or make them comprehensible or memorable. But seriously analyze the implications of any analogies you use. Calling a military action either “another Vietnam” or a “crusade” might raise serious issues, as does comparing one’s opponents to “Commies” or the KKK. Readers have a right to be skeptical of writers who use such ploys.

© Ariel Molvig/The New Yorker/Condé Nast.