Creating a structure

Creating a structure

organize information

How does a report work? Not like a shopping mall — where the escalators and aisles are designed to keep you wandering and buying, deliberately confused. Not like a mystery novel that leads up to an unexpected climax, or even like an argument, which steadily builds in power to a memorable conclusion. Instead, reports lay all their cards on the table right at the start and harbor no secrets. They announce what they intend to do and then do it, providing clear markers all along the way.

Clarity doesn’t come easily; it only seems that way when a writer has been successful. You have to know a topic in depth to explain it to others. Then you need to choose a structure that supports what you want to say. Among patterns you might choose for drafting a report are the following, some of which overlap. (develop a draft)

Organize by date, time, or sequence. Drafting a history report, you may not think twice about arranging your material chronologically: In 1958, the Soviet Union launched Sputnik, the first Earth satellite; in 1961, the Soviets launched a cosmonaut into Earth’s orbit; in 1969, the United States put two men on the moon. This structure puts information into a relationship readers understand immediately as a competition. You’d still have blanks to fill in with facts and details to tell the story of the race to the moon, but a chronological structure helps readers keep complicated events in perspective.

By presenting a simple sequence of events, you can use time to organize reports involving many kinds of information, from the scores in football games to the movement of stock markets to the flow of blood through the human heart. (shape your work)

Organize by magnitude or order of importance. Many reports present their subjects in sequence, ranked from biggest to smallest (or vice versa), most important to least important, most common/frequent to least, and so on. Such structures assume, naturally, that you have already done the research to position the items you expect to present. At first glance, reports of this kind might seem tailored to the popular media: “Ten Best Restaurants in Seattle,” “One Hundred Fattest American Cities.” But you might also use such a framework to report on the disputed causes of a war, the multiple effects of a stock market crash, or even the factors responsible for a disease.

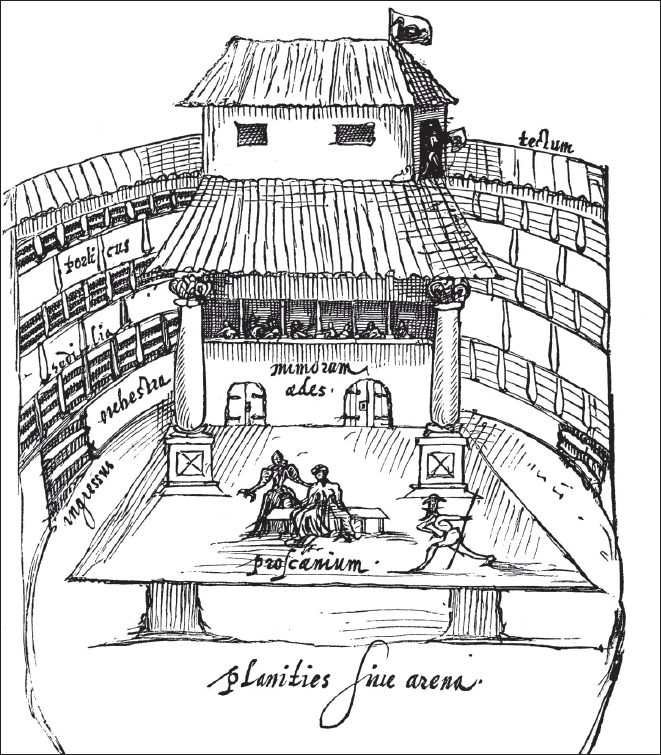

Organize by division. It’s natural to arrange some reports by simply breaking a subject into its major parts. A report on the federal government, for example, might be organized by treating each of its three branches in turn: executive, legislative, and judicial. A report on the Elizabethan stage might examine the individual parts of a typical theater: the “heavens,” the balcony, the stage wall, the stage, the pit, and so on. Of course, you’d then have to decide in what order to present the items, perhaps spatially or in order of importance. For example, you might use an illustration to clarify your report, working from top to bottom. Simple but effective.

Organize by classification. Classification is the division of a group of concepts or items according to specified and consistent principles. Reports organized by classification are easy to set up when you borrow a structure that is already well established — such as those that follow.

Psychology (by type of study): abnormal, clinical, comparative, developmental, educational, industrial, social

Psychology (by type of study): abnormal, clinical, comparative, developmental, educational, industrial, social Plays (by type): tragedy, comedy, tragicomedy, epic, pastoral, musical

Plays (by type): tragedy, comedy, tragicomedy, epic, pastoral, musical Nations (by form of government): monarchy, oligarchy, democracy, dictatorship

Nations (by form of government): monarchy, oligarchy, democracy, dictatorship Passenger cars (by engine placement): front engine, mid-

Passenger cars (by engine placement): front engine, mid-engine, rear engine  Dogs (by breed group): sporting, hound, working, terrier, toy, nonsporting, herding

Dogs (by breed group): sporting, hound, working, terrier, toy, nonsporting, herding

A project becomes more challenging when you try to create a new system —perhaps to classify the various political groups on your campus or to describe the behavior of participants in a psychology experiment. But such inventiveness can be worth the effort.

Organize by position, location, or space. Organizing a report spatially is a powerful strategy for arranging ideas — even more so today, given the ease with which material can be illustrated. (think visually) A map, for example, is a report organized by position and location. But it is only one type of spatial structure.

You use spatial organization in describing a painting from left to right, a building from top to bottom, a cell from nucleus to membrane. A report on medical conditions might be presented most effectively via cutaways that expose different layers of tissues and organs. Or a report on an art exhibition might follow a viewer through a virtual 3-

Organize by definition. Typically, definitions begin by identifying an object by its “genus” and “species” and then listing its distinguishing features, functions, or variations. This useful structure is the pattern behind most entries in dictionaries, encyclopedias, and other reference works. Once the genus and species have been established, you can expand a definition through explanatory details: Ontario is a province of Canada between Hudson Bay and the Great Lakes. That’s a good start, but what are its geographical features, history, products, and major cities — all the things that distinguish it from other provinces? You could write a book, let alone a report, based on this simple structure.

Organize by comparison/contrast. You probably learned this pattern in the fourth grade, but that doesn’t make comparison/contrast any less potent for college-

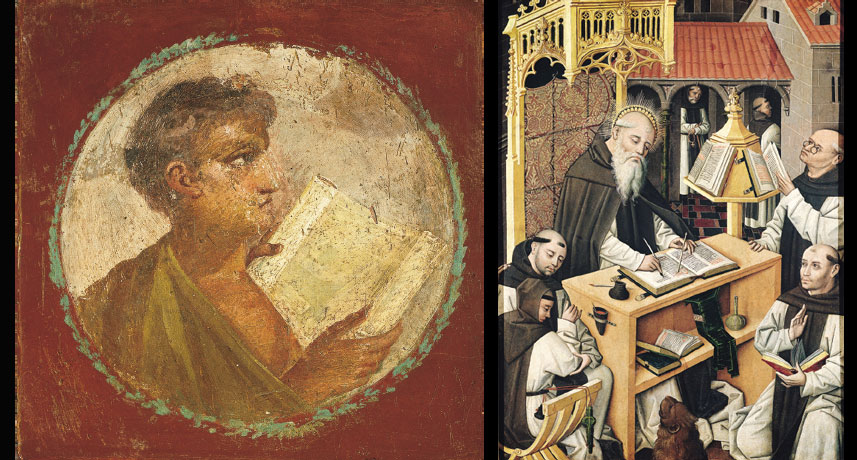

The images here compare two important “technologies” for reading, the scroll (left) and the codex (right). For a report contrasting these devices with the electronic screens readers use today, see Chapter 2.

Left: Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Naples, Italy/De Agostini Picture Library/The Bridgeman Art Library. Right: Museo Lazaro Galdiano, Madrid, Spain/The Bridgeman Art Library.

Organize by thesis statement. Obviously, you have many options for organizing a report; moreover, a single report might use several structural patterns. So it helps if you explain early in a report what its method of organization will be. That idea may be announced in a single thesis sentence, a full paragraph (or section), or even a PowerPoint slide. (develop a statement)

SENTENCE ANNOUNCES STRUCTURE

In the late thirteenth century, Native Puebloans may have abandoned their cliff dwellings for several related reasons, including an exhaustion of natural resources, political disintegration, and, most likely, a prolonged drought.

— Kendrick Frazier, People of Chaco: A Canyon and Its Culture

PARAGRAPH EXPLAINS STRUCTURE

In order to detect a problem in the beginning of life, medical professionals and caregivers must be knowledgeable about normal development and potential warning signs. Research provides this knowledge. In most cases, research also allows for accurate diagnosis and effective intervention. Such is the case with cri du chat syndrome (CDCS), also commonly known as cat cry syndrome.

— Marissa Dahlstrom, “Developmental Disorders: Cri du Chat Syndrome”