Strategies

Chapter Opener

25

develop a draft

Strategies

Strategies are patterns of writing that you will use in many situations and across many genres. This chapter looks at some of these essential tools, such as description, division, classification, definition, and comparison/contrast. While you may sometimes write “descriptions” for their own sake, or you may “compare and contrast” movies, smartphones, or college majors just for the heck of it, mostly you will draw upon these modes of writing to serve some larger purpose: to tell a story, clarify a point, or move an argument forward.

Use description to set a scene. Descriptions, which use language to re-

Malpais, translated literally from the Spanish, means “bad country.” In New Mexico, it signifies specifically those great expanses of lava flow which make black patches on the map of the state. The malpais of the Checkerboard country lies just below Mount Taylor, having been produced by the same volcanic fault that, a millennium earlier, had thrust the mountain fifteen thousand feet into the sky. Now the mountain has worn down to a less spectacular eleven thousand feet and relatively modern eruptions from cracks at its base have sent successive floods of melted basalt flowing southward for forty miles to fill the long valley between Cebolleta Mesa and the Zuni Mountains.

— Tony Hillerman, People of Darkness

Descriptions like this always involve selection. Just as a photographer carefully frames a subject, you have to decide which elements (visual, aural, tactile, and so on) in a scene will convey the situation most accurately, efficiently, or memorably and then turn them into words. Think nouns first, and only then modifiers: Adjectives and adverbs are essential, but it’s easy to ruin a description by overdressing it. Be specific, tangible, and honest. (improve your sentences)

A smart procedure is to write down everything you want to include in a descriptive passage and then cut out any words or phrases not pulling their weight. Be sure to sketch a scene that a reader can imagine easily, providing directions for the eyes and mind. The following descriptive paragraphs are from the opening of a student’s account of a trip she made to South Africa: Notice how lean and specific her sentences are, full of details that tell a story all on their own.

In Soweto, I am seventeen, curious, and in the largest shantytown in the world, so many thousands of miles away from my home. Streets are dusty, houses are made of cinderblock, and their yards are pressed-

Doors to homes are rare and inside I can see tired grandmothers with babies on their curved backs making spicy potjieko over smoky, single-

Soweto spreads over forty miles and nearly one million people call it home. It is a striking sight to see so close to the upscale suburbs of Johannesburg. There are row upon row of homemade houses, punctuated by schools and churches with fresh coats of paint from well-

— Lily Parish, “Sala Kahle, South Africa”

Use division to divide a subject. This strategy of writing is so common you might not notice it. A division involves no more than breaking a subject into its major components or enumerating its parts. In a report for an art history class, you might present a famous cathedral by listing and then describing its major architectural features, one by one: facade, nave, towers, windows, and so on. Or in a sports column on the Big Ten’s NCAA football championship prospects, you could just run through its roster of twelve teams. That’s a reasonable structure for a review, given the topic.

Division also puts ideas into coherent relationships that make them easier for readers to understand and use. The challenge comes when a subject doesn’t break apart as neatly as a tangerine. Then you have to decide which parts are essential and which are subordinate. Divisions of this sort are more than mechanical exercises: They require your clear understanding of a subject. For example, in organizing a Web site for your school or student organization, you’d probably start by deciding which aspects of the institution merit top-

Use classification to sort objects or ideas by consistent principles. Classification divides subjects up not by separating their parts but by clustering their elements according to meaningful or consistent principles. Just think of all the ways by which people can be classified:

Body type: endomorph, ectomorph, mesomorph

Hair color: black, brown, blond, red, gray, other

Weight: underweight, normal, overweight, obese

Sexual orientation: straight, bisexual, gay/lesbian, transgender

Race: black, Asian, white, other

Religion: Hindu, Buddhist, Muslim, Christian, Jew, other, no religion

Ideally, a principle of classification should apply to every member of the general class studied (in this case, people), and there would be no overlap among the resulting groups. But almost all useful efforts to classify complex phenomena —whether people, things, or ideas — have holes, gaps, or overlaps. Classifying people by religious beliefs, for instance, usually means mentioning the major groups and then lumping tens of millions of other people in a convenient category called “other.”

Even scientists who organize everything from natural elements to species of birds run into problems with creatures that cross boundaries (plant or animal?) or discoveries that upset familiar categories. You’ll wrestle with such problems routinely when, for instance, you argue about social policy.

Use definition to clarify meaning. Definitions don’t appear only in dictionaries. Like other strategies in this chapter, they occur in many genres. A definition might become the subject of a scientific report (What is a planet?), the bone of contention in a legal argument (How does the statute define life?), or the framework for a cultural analysis (Can a comic book be a serious novel?). In all such cases, writers need to know how to construct valid definitions.

Though definitions come in various forms, the classic dictionary definition is based on principles of classification discussed in the previous section. Typically a term is defined first by placing it in a general class. Then its distinguishing features or characteristics are enumerated, separating it from other members of the larger class. You can see the principle operating in this comic paragraph, which first fits “dorks” into the general class of “somebody,” that is to say, a person, and then claims two distinguishing characteristics.

It’s important to define what I truly mean by “dork,” just so he or she doesn’t get casually lumped in with “losers,” “burnouts” and “lone psychopath bullies.” To me, the dork is somebody who didn’t fit in at school and who therefore sought consolation in a particular field — computers, Star Trek, theater, heavy metal, medieval war reenactments, fantasy, sports trivia, even isolation sports like cross-

— Ian R. Williams, “Twilight of the Dorks?” Salon.com, October 23, 2003

In much writing, definitions become crucial when a question is raised about whether a particular object does or does not fit into a particular group. You engage in this kind of debate when you argue about what is or isn’t a sport, a hate crime, an act of terrorism, and so on. In outline form, the structure of such a discussion looks like this:

Defined group:

— General class

— Distinguishing characteristic 1

— Distinguishing characteristic 2 . . .

Controversial term

— Is / is not in the general class

— Does / does not share characteristic 1

— Does / does not share characteristic 2 . . .

Controversial term is/is not in the defined group

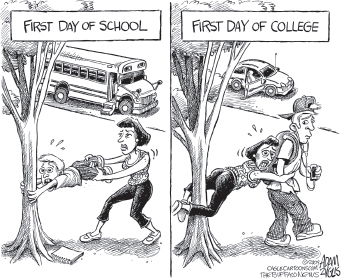

Use comparison and contrast to show similarity and difference. We seem to think better when we place ideas or objects side by side. So it’s not surprising that comparisons and contrasts play a role in all sorts of writing, especially reports, arguments, and analyses. Paragraphs are routinely organized to show how things are alike or different.

Adam Zyglis, The Buffalo News (blogs.buffalonews/adam-

The late 1960s and early 1970s were a time of cultural conflict, a battle between what I have called the beautiful people and the dutiful people. While Manhattan glitterati thronged Leonard Bernstein’s apartment to celebrate the murderous Black Panthers, ordinary people in the outer boroughs and the far-

— Michael Barone, “The Beautiful People vs. the Dutiful People,” U.S. News & World Report, January 16, 2006

Much larger projects can be built on similar structures of comparison and/or contrast.

To keep extended comparisons on track, the simplest structure is to evaluate one subject at a time, running through its features completely before moving on to the next. Let’s say you decided to contrast economic conditions in France and Germany. Here’s how such a paper might look in a scratch outline if you focused on the countries one at a time. (order ideas)

France and Germany: An Economic Report Card

- France

- Rate of growth

- Unemployment rate

- Productivity

- Gross national product

- Debt

- Germany

- Rate of growth

- Unemployment rate

- Productivity

- Gross national product

- Debt

The disadvantage of evaluating subjects one at a time is that actual comparisons, for example, of rates of employment in the outline above, might appear pages apart. So in some cases, you might prefer a comparison/contrast structure that looks at features point by point. (understand evaluations)

France and Germany: An Economic Report Card

- Rate of growth

- France

- Germany

- Unemployment rate

- France

- Germany

- Productivity

- France

- Germany

- Gross national product

- France

- Germany

- Debt

- France

- Germany