Beginning Your Research

Chapter Opener

37

plan a project

Beginning Your Research

Research can be part of any writing project. When doing research, you examine what is already known about a topic and then, sometimes, push the boundaries of knowledge forward. For humanities courses, this typically involves examining a wide range of books, articles, and Web sources. In the social and natural sciences, you might perform experiments or do field research and then share new data you have collected on a topic. For more on choosing a genre, see the Introduction.

So where do you begin your research project, and how do you keep from being swamped by the sheer quantity of information available? You need smart research strategies.

Know your assignment. When one is provided, review the assignment sheet for any project to establish exactly the kinds of research the paper requires. You may need to use only the reference section of the library for a one-

Come up with a plan. Research takes time because you have to find sources, read them, record your findings, and then write about them. Most research projects also require full documentation and some type of formal presentation, either as a research paper or, perhaps, an oral report. This stuff cannot be thrown together the night before. One way to avoid mayhem is to prepare a project calendar that ties specific tasks to specific dates. Simply creating the schedule (and you should keep it simple) might even jump-

Research is formalized curiosity. It is poking and prying with a purpose.

—Zora Neale Hurston

Photo by Carl Van Vechten/Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, LC-

Schedule: Research Paper

February 20: Topic proposal due

— Explore and select a topic

— Do preliminary library/Web research

— Define a thesis or hypothesis

— Prepare an annotated bibliography

March 26: First draft due

— Read, summarize, paraphrase, and synthesize sources

— Organize the paper

— Draft the paper

April 16: Final draft due

— Get peer feedback on draft

— Revise the project

— Check documentation

— Edit the project

Find a manageable topic. For a research project, this often means defining a problem you can solve with available resources. (For advice on finding and developing topics, see Part 3.) Look for a question within the scope of the assignment that you can answer in the time available.

When asked to submit a ten-

not Military Aircraft, but The Development of Jet Fighters in World War II

not The History of Punk Rock, but The Influence of 1970s Punk Rock on Nirvana

not Developmental Disorders in Children, but Cri du Chat Syndrome

It’s fine to read widely at first to find a general subject. But you have to narrow the project to a specific topic so that you can explore focused questions in your preliminary research. At this early stage in the research process, your goal is to turn a topic idea into a claim at least one full sentence long. (develop a statement)

In the natural and social sciences, topics sometimes evolve from research problems already on the table in various fields. Presented with such a research agenda, do a “review of the literature” to find out what represents state-

Web sites featuring government resources, such as Thomas or FedStats, and corporate annual reports provide primary material for analysis.

Left: Thomas/Library of Congress, http:/

Ask for help. During preliminary research, you’ll quickly learn that not all sources are equal. (find reliable sources) They differ in purpose, method, media, audience, and authority. Until you get your legs as a researcher, never hesitate to ask questions about research tools and strategies: Get recommendations about the best available journals, books, and authors from instructors and reference librarians. Ask them which publishers, institutions, and experts carry the most intellectual weight in their fields. If your topic is highly specialized, expect to spend additional time tracking down sources from outside your own library.

Books and magazines often provide secondary, not primary, information.

Top: Book-

Distinguish between primary and secondary sources. A primary source is a document that provides an eyewitness account of an event or phenomenon; a secondary source is a step or two removed, an article or book that interprets or reports on events and phenomena described in primary sources. The famous Zapruder film of the John F. Kennedy assassination in Dallas (November 22, 1963) is a memorable primary historical document; the many books or articles that draw on the film to comment on the assassination are secondary sources. Both types of sources are useful to you as a researcher.

Use primary sources when doing research that breaks new ground. Primary sources represent raw data — letters, journals, newspaper accounts, official documents, laws, court opinions, statistics, research reports, audio and video recordings, and so on. Working with primary materials, you generate your own ideas about a subject, free of anyone else’s opinions or explanations. Or you can review the actual evidence others have used to make their claims and arguments, perhaps reinterpreting their findings, correcting them, or bringing a new perspective to the subject.

Use secondary sources to learn what others have discovered or claimed about a subject. In many fields, you spend most of your time reviewing secondary materials, especially when a subject is new to you. Secondary sources include scholarly books and articles, encyclopedias, magazine pieces, and many Web sites. In academic assignments, you may find yourself moving between different kinds of materials, first reading a primary text like Hamlet and then reading various commentaries on it.

Record every source you examine. Whether you examine sources in libraries or look at them online, you must accurately list, right from the start, every research item you encounter, gathering the following information:

Authors, editors, translators, sponsors (of Web sites), or other major contributors

Authors, editors, translators, sponsors (of Web sites), or other major contributors Titles, subtitles, edition numbers, and volumes

Titles, subtitles, edition numbers, and volumes Publication information, including places of publication and publishers (for books); titles of magazines and journals, as well as volume and page numbers; dates of publication and access (the latter for online materials)

Publication information, including places of publication and publishers (for books); titles of magazines and journals, as well as volume and page numbers; dates of publication and access (the latter for online materials) Page numbers, URLs, electronic pathways, keywords, DOI (digital object identifier), or other locators

Page numbers, URLs, electronic pathways, keywords, DOI (digital object identifier), or other locators

You’ll need this information later to document your sources.

It might seem obsessive to collect so much data on books and articles you may not even use. But when you spend weeks or months on an assignment, you don’t want to have to backtrack, wondering at some point, “Did I read this source?” A log tells you whether you have.

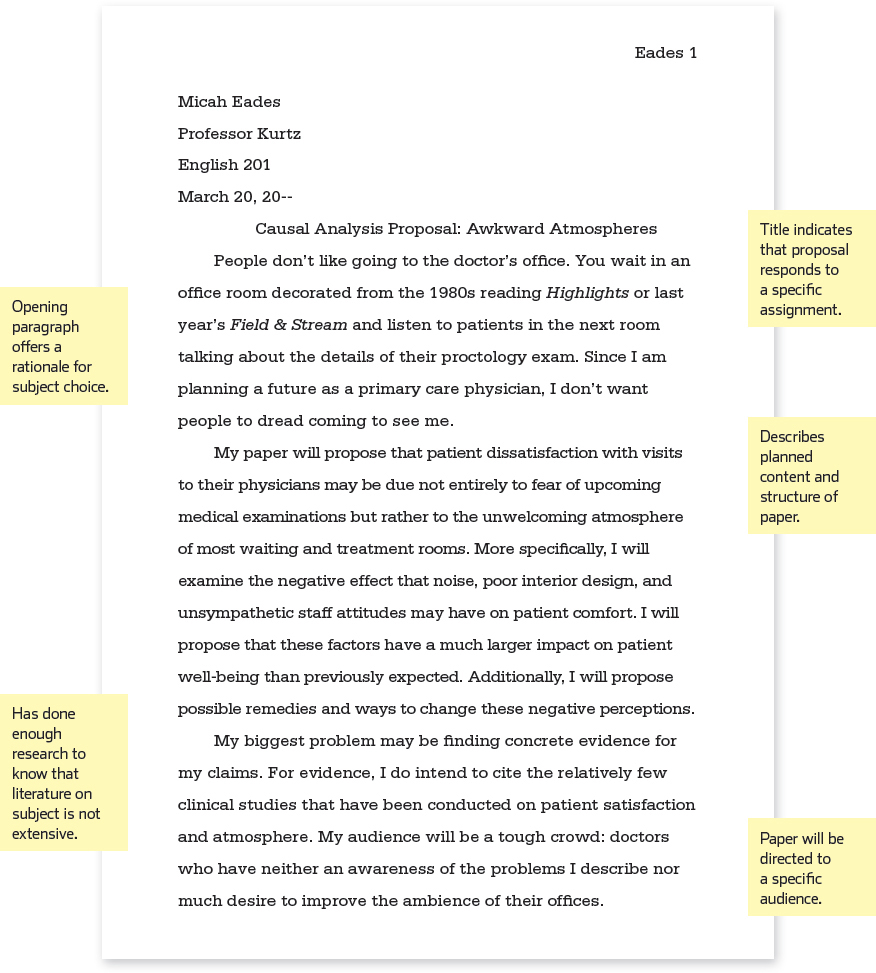

Prepare a topic proposal. Your instructor may request a topic proposal. Typically, this includes a topic idea, a draft thesis or hypothesis, potential sources, your intended approach, and a list of potential problems. It may also include an annotated bibliography of the books, articles, and other materials you anticipate using in your project — see Chapter 11 for more on annotated bibliographies.

Remember that such proposals are written to get feedback about your project’s feasibility and that even a good idea raises questions. The following sample proposal for a short project is directed chiefly at classmates, who must respond via electronic discussion board as part of the assignment.