Finding and developing materials

Finding and developing materials

develop support

You could write a book from the materials you’ll collect researching some arguments. Since arguments often deal with current events and topics, start with a resource such as the Yahoo! Directory’s “Issues and Causes” list mentioned earlier. Explore your subject, too, in LexisNexis, if your library gives you access to this huge database of newspaper articles. (refine your search)

As you gather materials, though, consider how much space you have to make your argument. Sometimes a claim has to fit within the confines of a letter to the editor, an op-

List your reasons. You’ll come up with reasons to support your claim almost as soon as you choose a subject. Write those down. Then start reading and continue to list new reasons as they arise, not being too fussy at this point. Be careful to paraphrase these ideas so that you don’t inadvertently plagiarize them later.

Then, when your reading and research are complete, review your notes and try to group the arguments that support your position. It’s likely you’ll detect patterns and relationships among these reasons, and an unwieldy initial list of potential arguments may be streamlined into just three or four — which could become the key reasons behind your claim. Study these points and look for logical connections or sequences. Readers will expect your ideas to converge on a claim or lead logically toward it. (shape your work)

Assemble your hard evidence. Gather examples, illustrations, quotations, and numbers to support each main point. Record these items as you read in some reliable way, keeping track of all bibliographical information (author, title, publication info, URL) just as you would when preparing a term paper — even if you aren’t required to document your argument. You want that data on hand in case your credibility is challenged later.

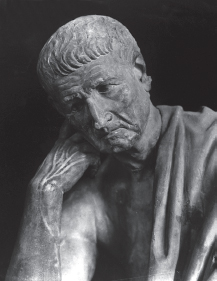

The whole is greater than the sum of its parts.

–Aristotle

Popperfoto/Getty Images.

If you borrow facts from a Web site, do your best to trace the information to its actual source. For example, if a blogger quotes statistics from the U.S. Department of Agriculture, find that table or graph on the USDA Web site itself and make sure the numbers reported are accurate. (analyze claims and evidence)

Cull the best quotations.You’ve done your homework for an assignment, reading the best available sources. So prove it in your argument by quoting from them intelligently. Choose quotations that do one or more of the following:

Put your issue in focus or context.

Put your issue in focus or context. Make a point with special power and economy.

Make a point with special power and economy. Support a claim or piece of evidence that readers might doubt.

Support a claim or piece of evidence that readers might doubt. State an opposing point well.

State an opposing point well.

Copy passages that appeal to you, but don’t figure on using all of them. An argument that is a patchwork of quotations reads like a patchwork of quotations — which is to say, boring. Be sure to copy the quotations accurately and be certain you can document them. (understand citation styles)

Find counterarguments. If you study a subject thoroughly, you’ll come across plenty of honest disagreement. List all reasonable objections you can find to your claim, either to your basic argument or to any controversial evidence you expect to cite. When possible, cluster these objections to reduce them to a manageable few. Decide which you must refute in detail, which you might handle briefly, and which you can afford to dismiss. (develop ideas)

Watch, for example, how in an editorial, the New York Times anticipates objections to its defense of a Rolling Stone magazine cover (August 2013) featuring accused Boston Marathon bomber Dzhokhar Tsarnaev. The Times concedes that merchants and consumers alike might resist the cover, but then it counterpunches:

Stores have a right to refuse to sell products because, say, they are unhealthy, like cigarettes. . . . Consumers have every right to avoid buying a magazine that offends them, like Guns & Ammo or Rolling Stone.

But singling out one magazine issue for shunning is over the top, especially since the photo has already appeared in a lot of prominent places, including the front page of this newspaper, without an outcry. As any seasoned reader should know, magazine covers are not endorsements.

— The Editorial Board, “Judging Rolling Stone by Its Cover,” New York Times, July 18, 2013

Consider emotional appeals. Feelings play a powerful role in many arguments, a fact you cannot afford to ignore when a claim you make stirs people up. Questions to answer about possible emotional appeals include the following:

What emotions might be effectively raised to support my point?

What emotions might be effectively raised to support my point? How might I responsibly introduce such feelings: through words, images,

How might I responsibly introduce such feelings: through words, images, color, sound?

color, sound? How might any feelings my subject arouses work contrary to my claims or reasons?

How might any feelings my subject arouses work contrary to my claims or reasons?

Well-

Jeff Foott/Discovery Channel Images/Getty Images.