Finding and developing materials

Finding and developing materials

develop ideas

With an assignment in hand and works to analyze, the next step — and it’s a necessary one — is to establish that you have a reliable “text” of whatever you’ll be studying. In a course, a professor may assign a particular edition or literary anthology for you to use, making your job easier.

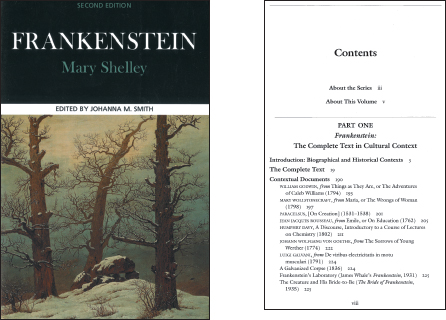

Be aware that many texts are available in multiple editions. (For instance, the novel Frankenstein first appeared in 1818, but the revised third edition of 1831 is the one most widely read today.) For classical works, such as the plays of Shakespeare, choose an edition from a major publisher, preferably one that includes thorough notes and perhaps some critical essays. When in doubt, ask your professor which texts to use. Don’t just browse the library shelves.

Other kinds of media pose interesting problems as well. For instance, you may have to decide which version of a movie to study — the one seen by audiences in theaters or the “director’s cut” on a DVD. Similarly, you might find multiple recordings of classical music: Look for widely respected performances. Even popular music may come in several versions: studio (American Idiot), live (Bullet in a Bible), alternative recording (American Idiot: The Original Broadway Cast Recording). Then there is the question of drama: Do you read a play on the page, watch a video when one is available, or see it in a theater? Perhaps you do all three. But whatever versions of a text you choose for study, be sure to identify them in your project, either in the text itself or on the works cited page. (understand citation styles)

Establishing a text is the easy part. Once that’s done, how do you find an angle on the subject? (find a topic) Try the following strategies and approaches.

Examine the text closely. Guided by your assignment, carefully read, watch, or examine the selected work(s) and take notes. Obviously, you’ll treat some works differently from others. You can read a Seamus Heaney sonnet a dozen times to absorb its nuances, but it’s unlikely you’d push through Rudolfo Anaya’s novel Bless Me, Ultima more than once or twice for a paper. But, in either case, you’ll need an effective way to keep notes or to annotate what you’re studying.

Honestly, you should count on a minimum of two readings or viewings of any text, the first one to get familiar with the work and find a potential approach, the second and subsequent ones to confirm your thesis and to find evidence for it. And do read the actual novel or play, not some “no fear” version.

Focus on the text itself. Your earliest literature papers probably tackled basic questions about plot, character, setting, theme, and language. But these are exactly the kinds of issues that fascinate many readers. So look for moments when the plot of the novel you’re analyzing establishes its themes or study how characters develop in response to specific events. Even the setting of a short story or film might be worth writing about when it becomes a factor in the story: Can you imagine the film Casablanca taking place in any other location?

Questions about language always loom large in literary analyses. How does word choice shape the mood of a poem? How does a writer create irony through diction or dialogue? Indeed, any technical feature of a work might be studied and researched, from the narrators in novels to the rhyme schemes in poetry.

Focus on meanings, themes, and interpretations. Although tracing themes in literary works seems like an occupation mostly for English majors, the impulse to find meanings is irresistible. If you take any work seriously, you’ll discover angles and ideas worth sharing with readers. Maybe Seinfeld is a modern version of Everyman, or O Brother, Where Art Thou? is a retelling of the Odyssey by Homer, or maybe not. Open your mind to possible connections: What have you seen like this before? What structural patterns do you detect? What ideas are supported or undercut?

Focus on authorship and history. Some artists stand apart from their creations, while others cannot be separated from them. So you might explore closely how a work mirrors the life, education, and attitudes of its author. Is the author writing to represent his or her gender, race, ethnicity, or class? Or does the work repudiate its author’s identity, class, or religion? What psychological forces or religious perspectives drive the work’s characters or themes?

Similarly, consider how a text embodies the assumptions, attitudes, politics, fashions, and even technology of the times during which it was composed. A work as familiar as Jonathan Swift’s “A Modest Proposal” still requires readers to know at least a little about Irish and English politics in the eighteenth century. How does Swift’s satire expand in scope when you learn a little more about its environment?

Focus on genre. Literary genres are formulas. Take a noble hero, give him a catastrophic flaw, have him make bad choices, and then kill him off: That’s tragedy — or, in the wrong hands, melodrama. With a little brainstorming, you could identify dozens of other genres and subcategories: epics, sonnets, historical novels, superhero comics, grand opera, soap opera, and so on. Artists often create works that fall between genres, sometimes producing new ones. Readers, too, bring clear-

You can analyze genre in various ways. For instance, track a text backward to discover its literary forebears — the works an author used for models. Even works that revolt against older genres bear traces of what their authors have rejected. It’s also possible to study the way artists combine different genres or play with or against the expectations of audiences. Needless to say, you can also explore the relationships of works within a genre. For example, what do twentieth-

Focus on influences. Some works have an obvious impact on life or society, changing how people think or behave: Uncle Tom’s Cabin, To Kill a Mockingbird, Roots, Schindler’s List. TV shows have broadened people’s notions of family; musical genres such as jazz and gospel have created and sustained entire communities.

But impact doesn’t always occur on such a grand scale or express itself through social movements. Books influence other books, films other films, and so on — with not a few texts crossing genres. For better or worse, books, movies, and other cultural productions influence styles, fashions, and even the way people speak. Consider Breaking Bad, Glee, or Game of Thrones. You may have to think outside the box, but projects that trace and study influence can shake things up.

Focus on social connections. In recent decades, many texts have been studied for what they reveal about relationships between genders, races, ethnicities, and social classes. Works by newer writers are now more widely read in schools, and hard questions are asked about texts traditionally taught: What do they reveal about the treatment of women or minorities? Whose lives have been ignored in “canonical” texts? What responsibility do such texts have for maintaining repressive political or social arrangements? Critical analyses of this sort have changed how many people view literature and art, and you can follow up on such studies and extend them to texts you believe deserve more attention.

Find good sources. Developing a literary paper provides you with many opportunities and choices. Fortunately, you needn’t make all your decisions on your own. Ample commentary and research are available on almost any literary subject or method, both in print and online. (refine your search) Your instructor and local librarians can help you focus on the best resources for your project, but the following boxes list some possibilities.

Literary Resources in Print

Abrams, M. H., and Geoffrey Harpham. A Glossary of Literary Terms. 11th ed., Cengage Learning, 2014.

Beacham, Walton, editor. Research Guide to Biography and Criticism. Beacham Publishing, 1990.

Birch, Dinah, editor. The Oxford Companion to English Literature. 7th ed., Oxford UP, 2009.

Crystal, David. The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Language. 3rd ed., Cambridge UP, 2010.

Encyclopedia of World Literature in the 20th Century. 3rd ed., St. James Press, 1999.

Gates, Henry Louis, Jr., et al. The Norton Anthology of African American Literature. 3rd ed., W. W. Norton, 2014.

Gilbert, Sandra M., and Susan Gubar. The Norton Anthology of Literature by Women: The Traditions in English. 3rd ed., W. W. Norton, 2007.

Greene, Roland, et al. The Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics. 4th ed., Princeton UP, 2012.

Harmon, William, and Hugh Holman. A Handbook to Literature. 12th ed., Prentice Hall, 2012.

Harner, James L. Literary Research Guide: A Guide to Reference Sources for the Study of Literature in English and Related Topics. 5th ed., The Modern Language Association of America, 2008.

Hart, James D., and Phillip W. Leininger. The Oxford Companion to American Literature. 6th ed., Oxford UP, 1995.

Howatson, M. C. The Oxford Companion to Classical Literature. 3rd ed., Oxford UP, 2011.

Leitch, Vincent, et al. The Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism. 2nd ed., Norton, 2010.

Sage, Lorna. The Cambridge Guide to Women’s Writing in English. Cambridge UP, 1999.

Literary Resources Online

Annual Bibliography of English Language and Literature (ABELL) (subscription)

The Atlantic (http:/

Browne Popular Culture Library (http:/

The Complete Works of William Shakespeare (shakespeare.mit.edu)

Eserver.org: Accessible Writing (http:/

A Handbook of Rhetorical Devices (http:/

Internet Public Library: Literary Criticism (http:/

Literary Resources on the Net (http:/

Literature Resource Center (Gale Group — subscription)

MLA on the Web (http:/

New York Review of Books (http:/

New York Times Book Review (http:/

The Online Books Page (onlinebooks.library.upenn.edu)

Yahoo! Arts: Humanities: Literature (http:/