Trade and “Colonization,” 800–580 B.C.E.

Printed Page 55

Important EventsTrade and “Colonization,” 800–580 B.C.E.

Greece’s jagged coastline made sea travel practical: almost every community lay within forty miles of the Mediterranean Sea. But seaborne commerce faced dangers from pirates and, especially, storms. As Hesiod commented, merchants took to the sea “because an income means life to poor mortals, but it is a terrible fate to die among the waves.”

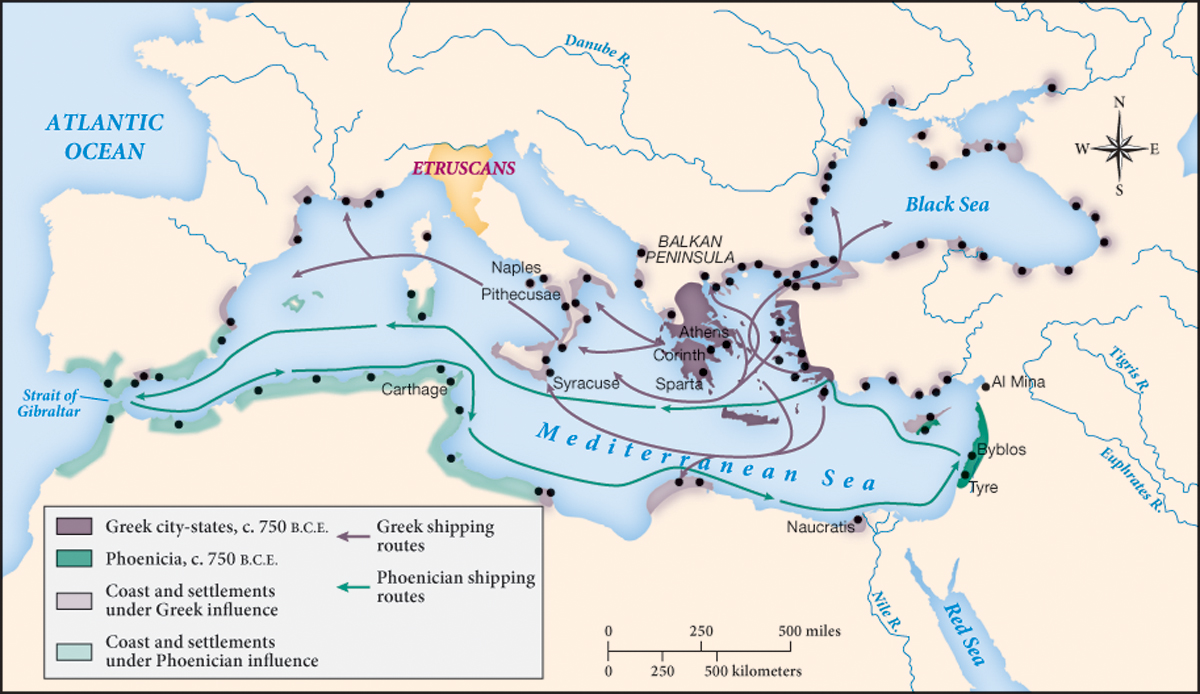

The Odyssey describes the basic strategy of Greek long-distance trade in commodities, when the goddess Athena appears disguised as a metal trader: “I am here . . . with my ship and crew on our way across the wine-dark sea to foreign lands in search of copper; I am carrying iron now.” By 800 B.C.E., the Mediterranean swarmed with entrepreneurs of many nationalities. The Phoenicians established settlements as far west as Spain’s Atlantic coast to gain access to inland mines there. Their North African settlement at Carthage (modern Tunis) would become one of the Mediterranean’s most powerful cities in later times.

The scale of trade soared near the end of the Dark Age: archaeologists have found only two tenth-century B.C.E. Greek pots that were carried abroad, but eighth-century pottery has turned up at more than eighty foreign sites. By 750 B.C.E., Greeks were settling far from home, sometimes living in others’ settlements, especially those of the Phoenicians, and sometimes establishing trading posts of their own, as the Euboeans did on an island in the Bay of Naples. Everywhere they traded with the local populations, such as the Etruscans in central Italy, who imported large amounts of Greek goods. Traders were not the only Greeks to emigrate. As the population expanded following the Dark Age, a shortage of farmland in Greece drove some poor farmers abroad to find fields they could work. Apparently only males left home on trading and land-hunting expeditions, so they had to find wives wherever they settled, either through peaceful negotiation or by kidnapping.

By about 580 B.C.E., Greek settlements had spread westward to Spain, present-day southern France, southern Italy, and Sicily; southward to North Africa; and eastward to the Black Sea coast (Map. 2.2). The settlements in southern Italy and Sicily, such as Naples and Syracuse, eventually became so large and powerful that this region was called Magna Graecia (“Great Greece”).

A Greek trading station had sprung up in Syria by 800 B.C.E., and in the seventh century B.C.E. the Egyptians permitted Greek merchants to settle in a coastal town. These close contacts with eastern Mediterranean peoples paid cultural as well as economic dividends. Near Eastern art inspired Greeks to reintroduce figures into their painting and provided models for statues that stood stiffly and stared straight ahead. When the improving economy of the later Archaic Age allowed Greeks again to afford monumental architecture in stone, their rectangular temples on platforms with columns reflected Egyptian architectural designs. (See “Seeing History: The Shift in Sculptural Style from Egypt to Greece.”)

Historians have traditionally called the Greeks’ settlement process in this era colonization, but recent research questions this term’s accuracy because the word colonization implies the process by which modern European governments officially installed dependent settlements and regimes abroad. The evidence for these Greek settlements suggests rather that private entrepreneurship created most of them. Official state involvement was minimal, at least in the beginning.