Creating New Kingdoms

Printed Page 123

Important EventsCreating New Kingdoms

Alexander’s successors divided his conquests among themselves. Antigonus (c. 382–301 B.C.E.) took over Anatolia, the Near East, Macedonia, and Greece; Seleucus (c. 358–281 B.C.E.) seized Babylonia and the East as far as India; and Ptolemy (c. 367–282 B.C.E.) took over Egypt. These successors had to create their own form of monarchy based on military power and personal prestige because they were self-proclaimed rulers with no connection to Alexander’s royal line.

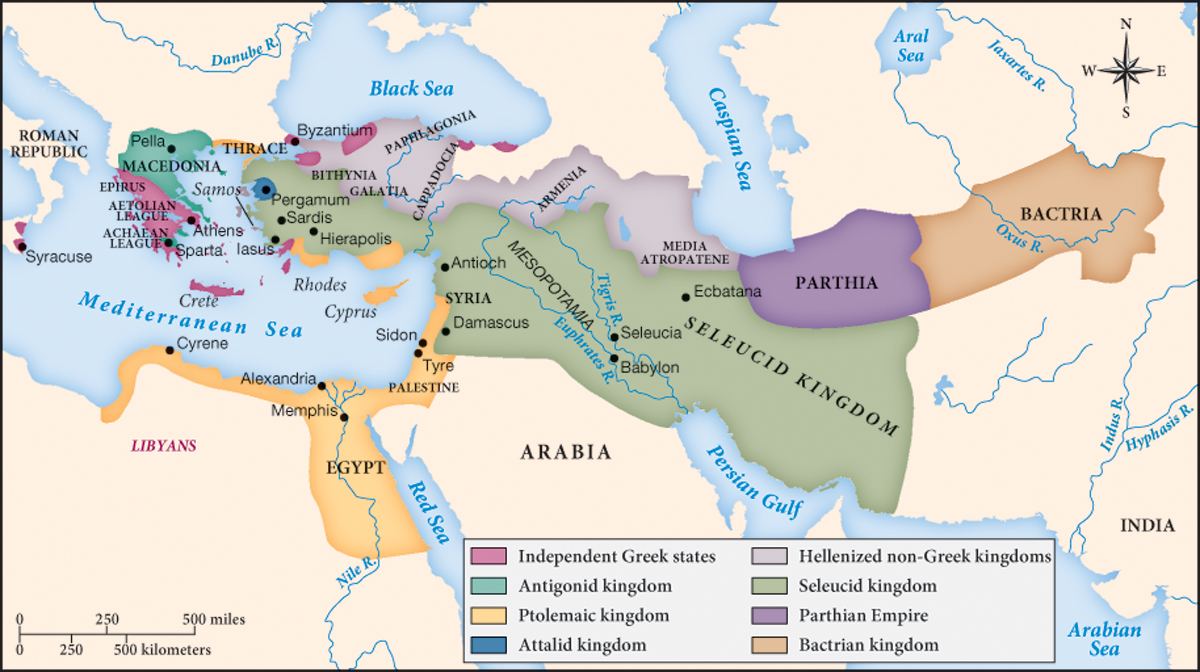

The kingdoms’ territories were never completely stable because the Hellenistic monarchs never stopped competing (Map 4.2). Conflicts repeatedly arose over border areas. The Ptolemies and the Seleucids, for example, fought to control the eastern Mediterranean coast, just like the Egyptians and Hittites. The wars between the major kingdoms created openings for smaller kingdoms to establish themselves. The most famous of these smaller kingdoms was that of the Attalids in western Anatolia, with the wealthy city of Pergamum as its capital. In Bactria in Central Asia, the Greeks—originally colonists settled by Alexander—broke off from the Seleucid kingdom in the mid-third century B.C.E. to found their own regional kingdom, which flourished for a time from the trade in luxury goods between India and China and the Mediterranean world.

The Hellenistic kingdoms imposed foreign rule by Macedonian kings and queens on indigenous populations. The kings incorporated local traditions into their rule to build legitimacy. The Ptolemaic royal family, for example, observed the Egyptian royal tradition of brother-sister marriage. Royal power was the ultimate source of control over the kingdoms’ subjects, in keeping with the Near Eastern monarchical tradition that Hellenistic kings adopted. Seleucus justified his rule on what he claimed as a universal truth of monarchy: “It is not the customs of the Persians and other people that I impose upon you, but the law which is common to everyone, that what is decreed by the king is always just.” The survival of these dynasties depended on their ability to create strong armies, effective administrations, and close ties to urban elites. A letter from a Greek city summed up the situation while praising the Seleucid king Antiochus I (c. 324–261 B.C.E.): “His rule depends above all on his own excellence [aretê], and on the goodwill of his friends, and on his forces.”

Professional soldiers manned Hellenistic royal armies and navies. To develop their military might, the Seleucid and Ptolemaic kings encouraged immigration by Greeks and Macedonians, who received land grants in return for military service. When this source of manpower gave out, the kings had to employ more local men as troops. Military competition put tremendous financial pressure on the kings to pay growing numbers of mercenaries and to purchase expensive new military technology. To compete effectively, a Hellenistic king had to provide giant artillery, such as catapults capable of flinging a 170-pound projectile up to two hundred yards. His navy cost a fortune because warships were now huge, requiring crews of several hundred men. War elephants became popular after Alexander brought them back from India, but they were extremely costly to maintain.

Hellenistic kings needed effective administrations to collect revenues. Initially, they recruited mostly Greek and Macedonian immigrants to fill high-level posts. The Seleucids and the Ptolemies also employed non-Greeks for middle- and low-level positions, where officials had to be able to deal with the subject populations and speak their languages. Local men who wanted a government job bettered their chances if they could read and write Greek in addition to their native language. Bilingualism qualified them to fill positions communicating the orders of the highest-ranking officials, all Greeks and Macedonians, to local farmers, builders, and crafts producers. Non-Greeks who had successful government careers were rarely admitted to royal society because Greeks and Macedonians saw themselves as too superior to mix with locals. Greeks and non-Greeks therefore tended to live in separate communities.

Administrators’ principal responsibilities were to maintain order and to direct the kingdoms’ tax systems. The Ptolemaic administration used methods of central planning and control inherited from earlier Egyptian history. Its officials continued to administer royal monopolies, such as that on vegetable oil, to maximize the king’s revenue. They decided how much land farmers could sow in oil-bearing plants, supervised production and distribution of the oil, and set prices for every stage of the oil business. The king, through his officials, also often entered into partnerships with private investors to produce more revenue.

Cities were the Hellenistic kingdoms’ economic and social hubs. Many Greeks and Macedonians lived in new cities founded by Alexander and the Hellenistic kings in Egypt and the Near East, and they also immigrated to existing cities there. Hellenistic kings promoted this urban immigration by adorning their new cities with the features of classical Greek city-states, such as gymnasia and theaters. Although these cities often retained the city-state’s political institutions, such as councils and assemblies for citizen men, the need to follow royal policy limited their freedom; they made no independent decisions on foreign policy. The cities taxed their populations to send money demanded by the king.

The crucial element in the Hellenistic kingdoms’ political and social structure was the system of mutual rewards by which the kings and their leading urban subjects became partners in government and public finance. Wealthy people in the cities were responsible for collecting taxes from the people in the surrounding countryside as well as from the city dwellers and sending the money on to the royal treasury. The kings honored and flattered the cities’ Greek and Macedonian social elites because they needed their cooperation to ensure a steady flow of tax revenues. When writing to a city’s council, a king would issue polite requests, but the recipients knew he was giving commands.

This system thus continued the Greek tradition of requiring the wealthy elite to contribute financially to the common good. Cooperative cities received gifts from the king to pay for expensive public works like theaters and temples or for reconstruction after natural disasters such as earthquakes. Wealthy men and women in turn helped keep the general population peaceful by subsidizing teachers and doctors, financing public works, and providing donations and loans to ensure a reliable supply of grain to feed the city’s residents.

To keep their vast kingdoms peaceful and profitable, the kings established relationships with well-to-do non-Greeks living in the old cities of Anatolia and the Near East. In addition, non-Greeks and non-Macedonians from eastern regions began moving westward to the new Hellenistic Greek cities in increasing numbers. Jews in particular moved from their ancestral homeland to Anatolia, Greece, and Egypt. The Jewish community eventually became an influential minority in Egyptian Alexandria, the most important Hellenistic city. In Egypt, as the Rosetta stone shows, the king also had to build good relationships with the priests who controlled the temples of the traditional Egyptian gods because the temples owned large tracts of rich land worked by tenant farmers.