Cultural and Religious Transformations

Printed Page 134

Important EventsCultural and Religious Transformations

Cultural transformations also shaped Hellenistic society. Wealthy non-Greeks increasingly adopted a Greek lifestyle to conform to the Hellenistic world’s social hierarchy. Greek became the common language for international commerce and cultural exchange. The widespread use of the simplified form of the Greek language called Koine (“shared” or “common”) reflected the emergence of an international culture based on Greek models; this was the reason the Egyptian camel trader stranded in Syria mentioned at the beginning of this chapter was at a disadvantage because he did not speak Greek. The most striking evidence of this cultural development comes from Afghanistan. There, King Ashoka (r. c. 268–232 B.C.E.), who ruled most of the Indian subcontinent, used Greek as one of the languages in his public inscriptions. These texts announced his plan to teach his subjects Buddhist self-control, such as abstinence from eating meat. Local languages did not disappear in the Hellenistic kingdoms, however. In one region of Anatolia, for example, people spoke twenty-two different languages.

Religious diversity also grew. Traditional Greek cults (as described in “Religious Tradition in a Period of Change” in Chapter 3) remained popular, but new cults, especially those deifying kings, reflected changing political and social conditions. Preexisting cults that previously had only local significance gained adherents all over the Hellenistic world. In many cases, Greek cults and local cults from the eastern Mediterranean influenced each other. Sometimes, local cults and Greek cults existed side by side and even overlapped. Some Egyptian villagers, for example, continued worshipping their traditional crocodile god and mummifying their dead, but they also honored Greek deities. As polytheists (believers in multiple gods), people could worship in both old and new cults.

New cults incorporated a concern for the relationship between the individual and what seemed the arbitrary power of divinities such as Tychê (“chance” or “luck”). Since advances in astronomy had furthered knowledge about the movement of the universe’s celestial bodies, religion now had to address the disconnect between “heavenly uniformity” and the “shapeless chaos of earthly life.” One increasingly popular approach to bridging that gap was to rely on astrology, which was based on the movement of the stars and planets, thought of as divinities. Another common choice was to worship Tychê in the hope of securing good luck in life.

The most revolutionary approach in seeking protection from Tychê’s unpredictable tricks was to pray for salvation from deified kings, who expressed their divine power in ruler cults. Various populations established these cults in recognition of great benefactions. The Athenians, for example, deified the Macedonian Antigonus and his son Demetrius as savior gods in 307 B.C.E., when they liberated the city and bestowed magnificent gifts on it. Like most ruler cults, this one expressed the population’s spontaneous gratitude to the rulers for their salvation, in hopes of preserving the rulers’ goodwill toward them by addressing the kings’ own wishes to have their power respected. Many cities in the Ptolemaic and Seleucid kingdoms set up ruler cults for their kings and queens. An inscription put up by Egyptian priests in 238 B.C.E. concretely described the qualities appropriate for a divine king and queen who brought physical salvation:

King Ptolemy III and Queen Berenice, his sister and wife, the Benefactor Gods, . . . have provided good government . . . and [after a drought] sacrificed a large amount of their revenues for the salvation of the population, and by importing grain . . . they saved the inhabitants of Egypt.

The Hellenistic monarchs’ tremendous power and wealth gave them the status of gods to the ordinary people who depended on their generosity and protection. The idea that a human being could be a god, present on earth to save people from evils, was now firmly established and would prove influential later in Roman imperial religion and Christianity.

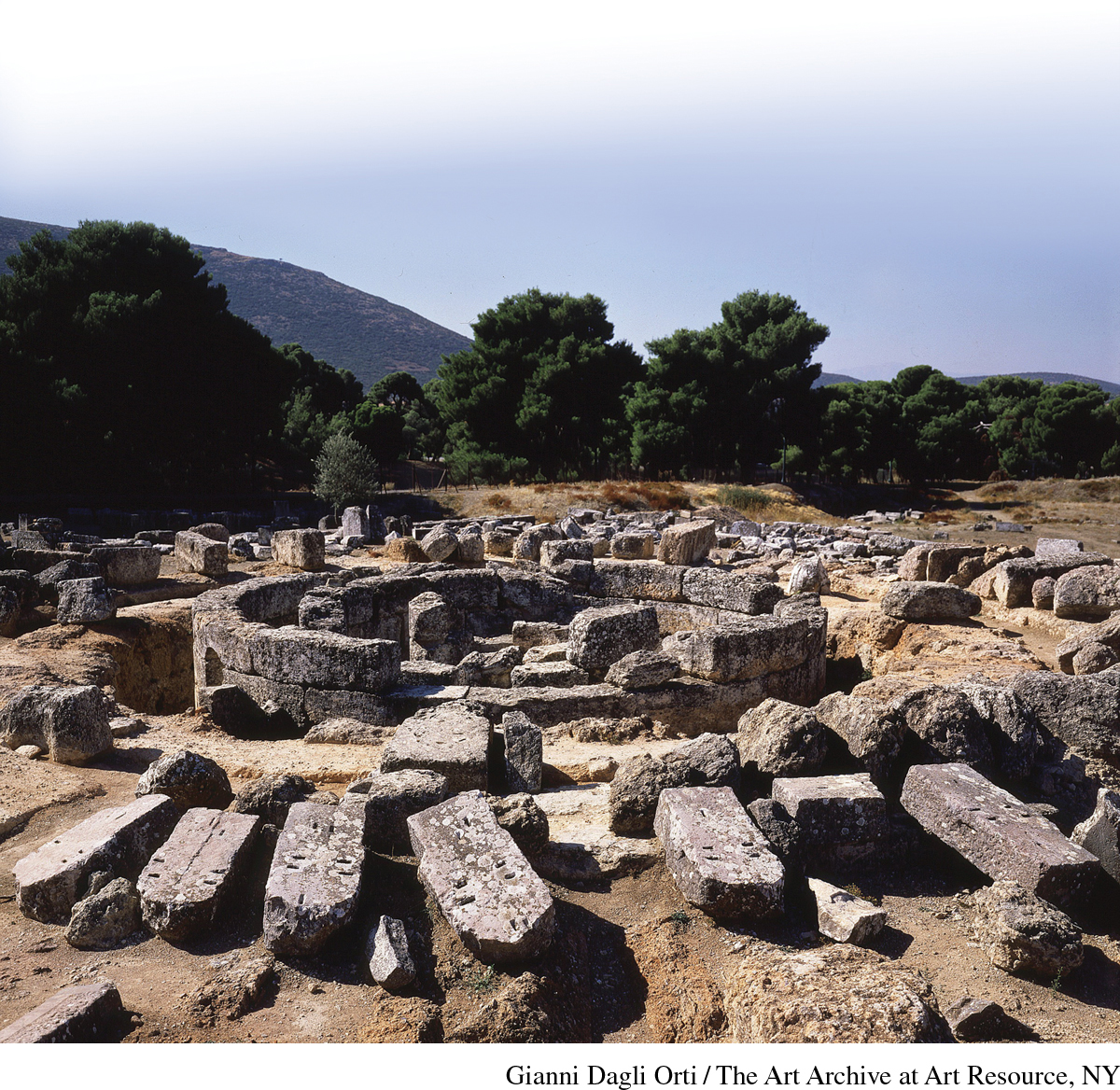

Healing divinities offered another form of protection to anxious individuals. The cult of the god Asclepius, who offered cures for illness and injury at his many shrines, grew in popularity during the Hellenistic period. Suppliants seeking Asclepius’s help would sleep in special locations at his shrines to await dreams in which he prescribed healing treatments. These prescriptions emphasized diet and exercise, but numerous inscriptions commissioned by grateful patients also testified to miraculous cures and surgery performed while the sufferer slept. The following example is typical:

Ambrosia of Athens was blind in one eye. . . . She . . . ridiculed some of the cures [described in inscriptions in the sanctuary] as being incredible and impossible. . . . But when she went to sleep, she saw a vision; she thought the god was standing next to her. . . . He split open the diseased eye and poured in a medicine. When day came she left cured.

People’s faith in divine healing gave them hope that they could overcome the constant danger of illness, which appeared to strike at random; there was no knowledge of germs as causing infections.

Mystery cults promised initiates secret knowledge for salvation. The cults of the Greek god Dionysus and the Egyptian goddess Isis attracted many people. Isis became the most popular female divinity in the Mediterranean because her powers protected her worshippers in all aspects of their lives. Her cult involved rituals and festivals mixing Egyptian religion with Greek elements. Disciples of Isis strove to achieve personal purification and the goddess’s aid in overcoming the demonic power of Tychê. This popularity of an Egyptian deity among Greeks (and, later, Romans) is clear evidence of the cultural interaction of the Hellenistic world.

Cultural interaction between Greeks and Jews influenced Judaism during the Hellenistic period. King Ptolemy II made the Hebrew Bible accessible to a wide audience by having his Alexandrian scholars produce a Greek translation—the Septuagint. Many Jews, especially those in the large Jewish communities that had grown up in Hellenistic cities outside their homeland, began to speak Greek and adopt Greek culture. These Greek-style Jews mixed Jewish and Greek customs, while retaining Judaism’s rituals and rules and not worshipping Greek gods.

Internal conflict among Jews erupted in second-century B.C.E. Palestine over how much Greek tradition was acceptable for traditional Jews. The Seleucid king Antiochus IV (r. 175–164 B.C.E.) intervened to support Greek-style Jews in Jerusalem, who had taken over the high priesthood that ruled the Jewish community. In 167 B.C.E., Antiochus converted the great Jewish temple in Jerusalem into a Greek temple and outlawed Jewish religious rites such as observing the Sabbath and performing circumcision. This action provoked a revolt led by Judah the Maccabee, which won Jewish independence from Seleucid control after twenty-five years of war. The most famous episode in this revolt was the retaking of the Jerusalem temple and its rededication to the worship of the Jewish god, Yahweh, commemorated by the Hanukkah holiday.

REVIEW QUESTION How did the political changes of the Hellenistic period affect art, science, and religion?

That Greek culture attracted some Jews in the first place provides a striking example of the transformations that affected many—though far from all—people of the Hellenistic world. By the time of the Roman Empire, one of those transformations would be Christianity, whose theology had roots in the cultural interaction of Hellenistic Jews and Greeks and their ideas on apocalypticism (religious ideas revealing the future) and divine human beings.