Roman Society under the Kings, 753–509 B.C.E.

Printed Page 150

Important EventsRoman Society under the Kings, 753–509 B.C.E.

Seven kings ruled from 753 to 509 B.C.E. and created Rome’s most famous and enduring government body: the Senate, a group of distinguished men chosen as the king’s personal council. This council played the same role—advising government leaders—for a thousand years, as Rome changed from a monarchy to a republic and back to a monarchy (the empire). It was always a Roman tradition that one should never make decisions by oneself but only after consulting advisers and friends.

Rome’s expansion depended on taking in outsiders conquered in war and, uniquely in the ancient world, freed slaves. Though freedmen and freedwomen owed special obligations to their former owners and could not hold elective office or serve in the army, they enjoyed all other citizens’ rights, such as legal marriage. Their children possessed citizenship without any limits. By the late republic, many Roman citizens were descendants of freed slaves.

By 550 B.C.E., Rome had grown to some forty thousand people and, through war and diplomacy, had won control of three hundred square miles of surrounding territory. Recent archaeological excavation confirms that the Romans had already built substantial temples to their gods by this date. Rome’s geography propelled its further expansion. The Romans originated in central Italy, a long peninsula with a mountain range down its middle like a spine and fertile plains on either side. Rome also controlled a river crossing on a major north–south route. Most important, Rome was ideally situated for international trade: the Italian peninsula stuck so far out into the Mediterranean that east–west seaborne traffic naturally encountered it (Map 5.1), and the city had a good port nearby.

The Italian ancestors of the Romans lived by herding animals, farming, and hunting. They became skilled metalworkers, especially in iron. The earliest Romans’ neighbors in central Italy were poor villagers, too, and spoke the same language, Latin. Greeks lived to the south in Italy and Sicily, and contact with them deeply affected Roman cultural development. Romans developed a love-hate relationship with Greece, admiring its literature and art but looking down on its lack of military unity. Romans adopted many elements from Greek culture—from the deities for their national cults to the models for their poetry, prose, and architectural styles.

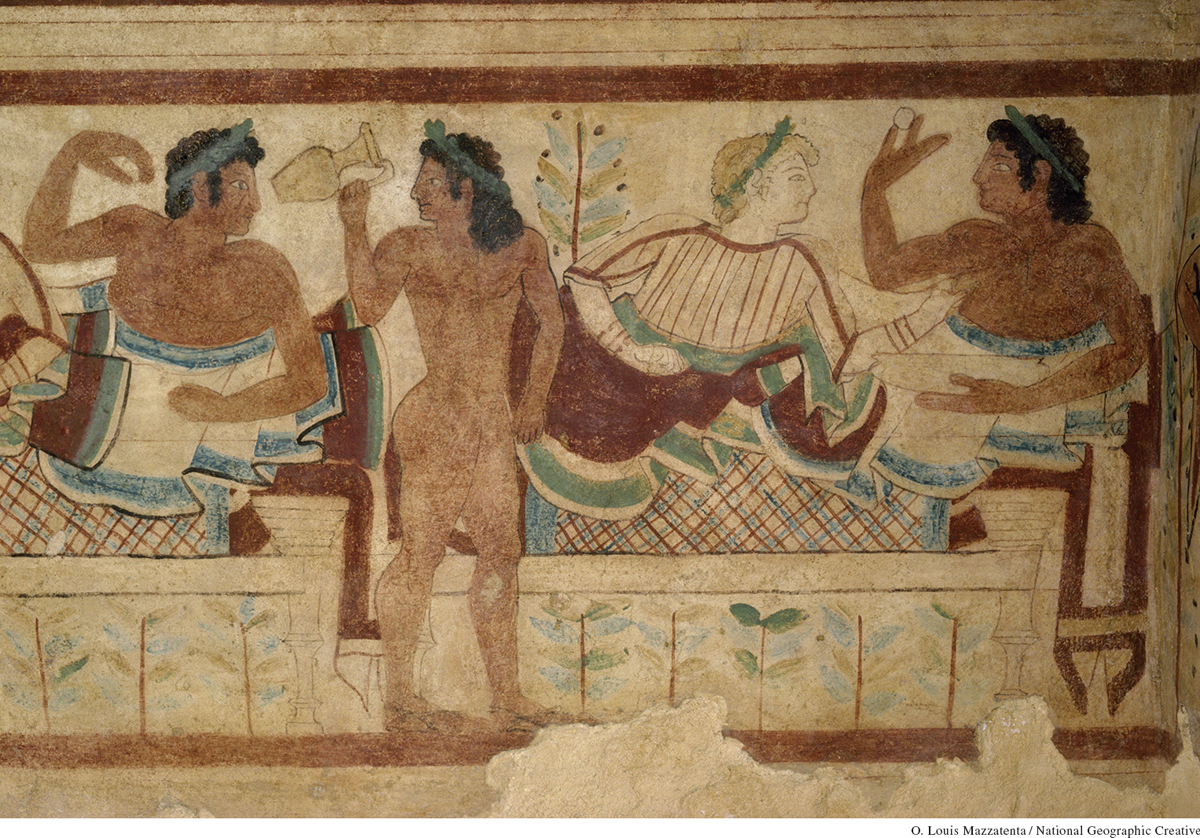

The Etruscans, a people to the north, also influenced Roman culture. Brightly colored wall paintings in tombs, portraying funeral banquets and festive games, reveal the splendor of Etruscan society. In addition to producing their own art, jewelry, and sculpture, the Etruscans imported luxurious objects from Greece and the Near East. Most of the intact Greek vases known today were found in Etruscan tombs, and Etruscan culture was deeply influenced by that of Greece.

Romans adopted ceremonial features of Etruscan culture, such as musical instruments, religious rituals, and lictors (attendants who walked before the highest officials carrying the fasces, a bundle of rods around an ax, symbolizing the officials’ right to command and punish). The Romans also borrowed from the Etruscans the ritual of divination—determining the will of the gods by examining organs of slaughtered animals. Other prominent features of Roman culture were probably part of the ancient Mediterranean’s shared practices, such as the organization of the Roman army (a citizen militia of heavily armed infantry troops fighting in formation) and the use of an alphabet.