Christianity and Classical Culture in the British Isles

Printed Page 269

Important EventsChristianity and Classical Culture in the British Isles

The Merovingian kingdoms exemplify some of the ways in which Roman and non-Roman traditions combined; the British Isles show others. Ireland had never been part of the Roman Empire, but the Irish people were early converts to Christianity, as were people in Roman Britain and parts of Scotland. Invasions by various Celtic and Germanic groups—particularly the Anglo-Saxons, who gave their name to England (“land of the Angles”)—redrew the religious boundaries. Ireland, largely free of invaders, remained Christian. Scotland, also relatively untouched by invaders, had been slowly Christianized by the Irish from the west and in early years by the British from the south. England, which emerged from the invasions as a mosaic of about a dozen kingdoms ruled by separate Anglo-Saxon kings, became largely pagan until it was actively converted in the seventh century.

Christianity was introduced to Anglo-Saxon England from two directions. To the north, Irish monks brought their own brand of Christianity. Converted in the fifth century by St. Patrick and other missionaries, the Irish had evolved a church organization that corresponded to its rural clan organization. Abbots and abbesses were more powerful than bishops there. The Irish missionaries to England were monks, and they set up monasteries modeled on those at home—out in the countryside.

In the south, Christianity came to England in 597 via missionaries sent by the pope known as Gregory the Great (r. 590–604). These men, led by Augustine (not the same Augustine as the bishop of Hippo as discussed on page 224), intended to convert the king and people of Kent, the southernmost kingdom, and then work their way northward. Augustine and his party brought with them Roman practices at odds with those of Irish Christianity, stressing ties to the pope and the authority of bishops. Using the Roman model, they divided England into territorial units, called dioceses, headed by an archbishop and bishops. Augustine became archbishop of Canterbury. Because he was a monk, he set up a monastery right next to his cathedral, and having a community of monks attached to the bishop’s church became a characteristic of the English church. Later a second archbishopric was added at York.

A major bone of contention between the Roman and Irish churches involved the calculation of the date of Easter, celebrated by Christians as the day on which Christ rose from the dead. Because everyone agreed that believers could not be saved unless they observed Christ’s resurrection properly and on the right date, the conflict was bitter. It was resolved by Oswy, king of Northumbria, who organized a meeting of churchmen, the Synod of Whitby, in 664. Convinced that Rome spoke with the voice of St. Peter, who was said in the New Testament to hold the keys of the kingdom of heaven, Oswy chose the Roman date. His decision paved the way for the triumph of the Roman brand of Christianity in England.

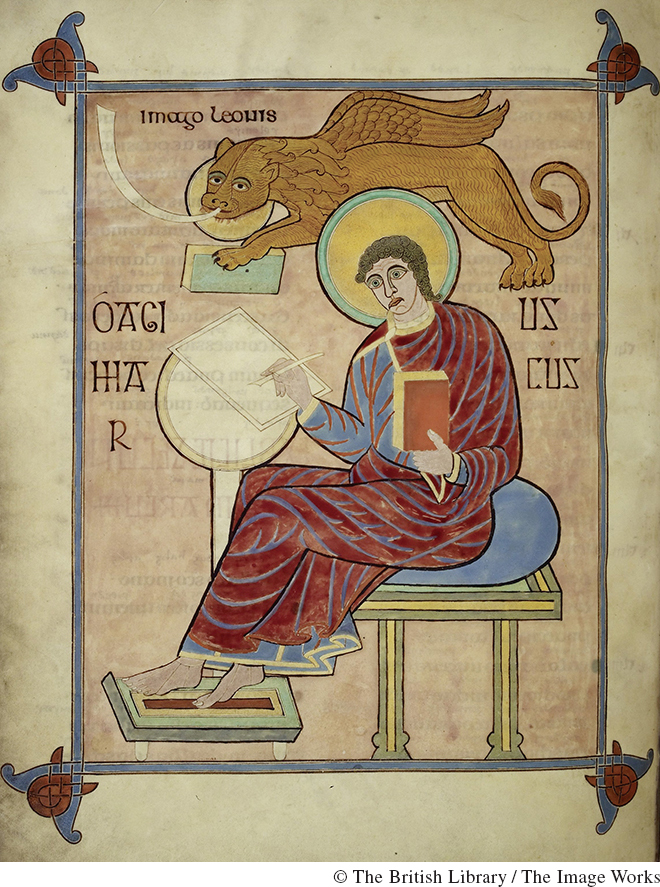

The authority of St. Peter was only one of the attractions of Roman Christianity. Rome had great prestige as a treasure trove of knowledge, piety, and holy objects. Benedict Biscop (c. 630–690), the founder of two important English monasteries, made many difficult trips to Rome, bringing back relics, liturgical vestments, and even a cantor to teach his monks the proper melodies in a time before written musical notation. Above all, he went to Rome to get books. At his monasteries in the north of England, he built up a grand library. In Anglo-Saxon England, as in Scotland and Ireland, all of which lacked a strong classical tradition from Roman times, a book was considered a precious object, to be decorated as finely as a jewel-studded reliquary (see the chapter-opening image).

The Anglo-Saxons and Irish Celts had a thriving oral culture but extremely limited uses for writing. Books became valuable only when these societies converted to Christianity. Just as Islamic reliance on the Qur’an made possible a literary culture under the Umayyads, so Christian dependence on the Bible, liturgy, and the writings of the church fathers helped make England and Ireland centers of literature and learning in the seventh and eighth centuries. Men like Benedict Biscop soon sponsored other centers of learning, using texts from the classical past. Although women did not establish famous schools, many abbesses ruled over monasteries that stressed Christian learning. Latin writings, even pagan texts, were studied diligently, in part because Latin was so foreign a language on the British Isles that mastering it required systematic and formal study. One of Benedict Biscop’s pupils was Bede (“the Venerable,” 673–735), an Anglo-Saxon monk and a historian of extraordinary breadth. Bede in turn taught a new generation of monks who became advisers to eighth-century rulers.

Much of the vigorous pagan Anglo-Saxon oral tradition was adapted to Christian culture. Bede encouraged and supported the use of the Anglo-Saxon language, urging priests, for example, to use it when they instructed their flocks. In contrast to other European regions, where Latin was the primary written language in the seventh and eighth centuries, England made use of the vernacular—the language normally spoken by the people. Written Anglo-Saxon (or Old English) was used in every aspect of English life, from government to entertainment.

The decision at the Synod of Whitby to favor Roman Christianity tied the English church to Rome by doctrine, friendship, and conviction. The Anglo-Saxon monk and bishop Wynfrith took the Latin name Boniface to symbolize his loyalty to the Roman church. Preaching on the continent, Boniface (680–754) set up churches in Germany and Gaul that, like those in England, looked to Rome for leadership and guidance. Boniface was one of those travelers from Rome who went to Trier to check on the bishop’s piety. He found it badly wanting! Boniface’s efforts to reform the Frankish church gave the papacy new importance in Europe.