New Syntheses in Writing and Music

Printed Page 387

Important EventsNew Syntheses in Writing and Music

Thirteenth-century vernacular writers, like scholastics, synthesized seemingly contradictory ideas. Dante Alighieri (1265–1321) harmonized the mysteries of faith with the poetry of love. Born in Florence in a time of political turmoil, Dante incorporated the major figures of history and his own day into his most famous poem, Commedia, written between 1313 and 1321. Later known as Divina commedia (Divine Comedy), Dante’s poem describes the poet taking an imaginary journey from hell to purgatory and finally to paradise. At the most literal level, the poem is about Dante’s travels. At a deeper level, it is about the soul’s search for meaning and enlightenment and its ultimate discovery of God in the light of divine love. Just as Thomas Aquinas employed Aristotle’s logic to reach important truths, so Dante used the pagan poet Virgil as his guide through hell and purgatory. And just as Thomas believed that faith went beyond reason to even higher truths, so Dante found a new guide representing earthly love to lead him through most of paradise. That guide was Beatrice, a Florentine girl with whom Dante had fallen in love as a boy and whom he never forgot. But only faith, in the form of the divine love of the Virgin Mary, could bring Dante to the culmination of his journey—a blinding and inexpressibly awesome vision of God.

Dante’s poem electrified a wide audience. By elevating one dialect of Italian—the language that ordinary Florentines used in their everyday life—to a language of exquisite poetry, Dante was able to communicate an orderly and optimistic vision of the universe in an even more exciting and accessible way than the scholastics had. So influential was his work that it is no exaggeration to say that modern Italian is based on Dante’s Florentine dialect.

Other writers of the period used different methods to express the harmony between heaven and earth. The anonymous author of the Quest of the Holy Grail (c. 1225), for example, wrote about the adventures of some of the knights of King Arthur’s Round Table to convey the doctrine of transubstantiation and the wonder of the vision of God. (See “Document 12.2: The Debate between Reason and the Lover.”)

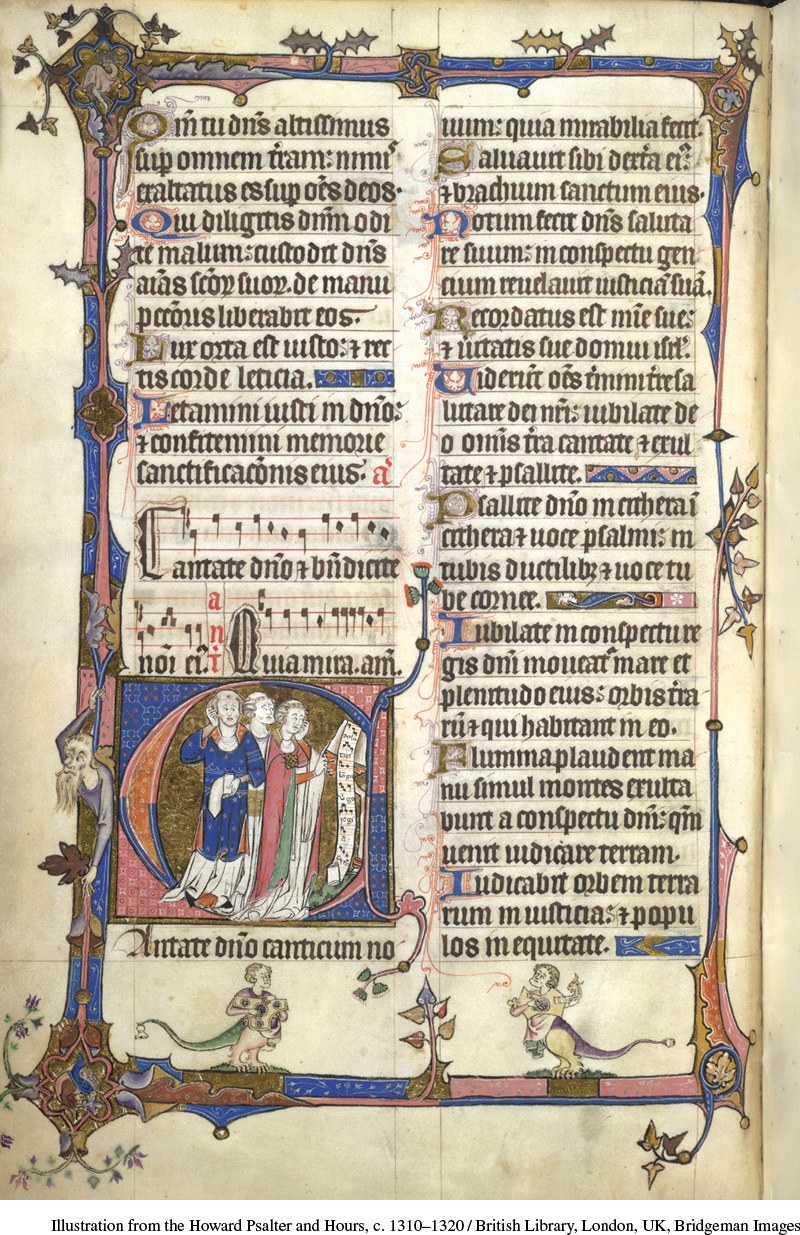

Just as vernacular writers asserted the harmony of heavenly and earthly things, so musicians combined sacred and secular music. This was quite new. The music before this time, plainchant (See “Architectural Style: From Romanesque to Gothic” in Chapter 11), had a particular sequence of notes for a given text. It is true that sometimes a form of harmony was achieved when two voices sang exactly the same melody an interval apart. This was the first form of polyphony, the simultaneous sounding of two or more melodies. In the twelfth century, musicians experimented with freer melodies. One voice might go up the scale, for example, while the other went down, achieving even so a pleasing harmony. Or one voice might hold a pitch while the other danced around it.

Now, in the thirteenth century, some musicians put secular and sacred tunes together. This form of music, which probably originated in Paris, was called the motet (from the French mot, meaning “word”). It typically had two or three melody lines, or “voices.” The lowest was usually a plainchant melody sung in Latin. The remaining melodies had different texts, either Latin or French (or one of each), which were sung simultaneously. Latin texts were usually sacred, whereas French ones were secular, dealing with themes such as love and springtime. The motet thus wove the sacred (the chant melody in the lowest voice) and the secular (the French texts in the upper voices) into a sophisticated tapestry of words and music.

Like the scholastic summae, motets were written by and for a clerical elite. Yet they incorporated the music of ordinary people, such as the calls of street vendors and the boisterous songs of students. In turn, they touched the lives of everyone, for polyphony influenced every form of music, from the Mass to popular songs that entertained laypeople and churchmen alike.

Complementing the motet’s complexity was the development of a new notation for rhythm. Music theorists of the thirteenth century developed increasingly precise methods to indicate rhythm, with each note shape allotted a specific duration. The music of the thirteenth century reflected both the melding of the secular and the sacred and the possibilities of greater order and control.