Political Revolts in the 1820s

Printed Page 662

Important EventsPolitical Revolts in the 1820s

The restoration of regimes after Napoleon’s fall disappointed those who dreamed of constitutional freedoms and national independence. Membership grew in secret societies such as the carbonari, attracting tens of thousands of members. Revolts broke out in the 1820s in Spain, Italy, Russia, and Greece (Map 20.3), as well as across the Atlantic in the Spanish and Portuguese colonies of Latin America (see page 665).

When Ferdinand VII regained the Spanish crown in 1814, he ordered foreign books and newspapers to be confiscated at the frontier and allowed the publication of only two newspapers. Many army officers who had encountered French ideas responded by joining secret societies. In 1820, disgruntled soldiers demanded that Ferdinand proclaim his adherence to the constitution of 1812, which he had abolished in 1814. Ferdinand bided his time, and in 1823 a French army invaded and restored him to absolute power. The French acted with the consent of the other great powers. The restored Spanish government tortured and executed hundreds of rebels; thousands were imprisoned or forced into exile.

Hearing of the Spanish uprising, rebellious soldiers in the kingdom of Naples joined forces with the carbonari and demanded a constitution. The promise of reform sparked rebellion in the northern Italian kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia, where rebels urged Charles Albert, the young heir to the Piedmont throne, to fight the Austrians for Italian unification. After the rulers of Austria, Prussia, and Russia met and agreed on intervention in 1821, the Austrians defeated the rebels in Naples and Piedmont. Although Great Britain condemned the indiscriminate suppression of revolutionary movements, Metternich convinced the other powers to agree to his silencing the Italian opposition to Austrian rule.

Metternich acted quickly to suppress any sign of dissent closer to home. University students had formed nationalist student societies called Burschenschaften, and in 1817 they held a mass rally at which they burned books they did not like, including Napoleon’s Civil Code. Metternich was convinced—incorrectly—that the Burschenschaften in the German states and the carbonari in Italy were linked in an international conspiracy. In 1819, when a student assassinated the playwright August Kotzebue because he had ridiculed the student movement, Metternich convinced the leaders of the biggest German states to pass the Carlsbad Decrees, dissolving the student societies and more strictly censoring the press. Professors who criticized their rulers were immediately fired.

Aspirations for constitutional government surfaced in Russia when Alexander I died suddenly in 1825. In December, when the troops assembled in St. Petersburg to take an oath of loyalty to Alexander’s brother Nicholas as the new tsar, rebel officers insisted that the crown belonged to another brother, Constantine, whom they hoped would be more favorable to constitutional reform. Constantine, though next in the line of succession after Alexander, had refused the crown. Soldiers loyal to Nicholas easily suppressed the Decembrist Revolt (so called after the month of the uprising). The subsequent trial, however, made the rebels into legendary heroes. For the next thirty years, Nicholas I (r. 1825–1855) used a new political police, the Third Section, to spy on potential opponents and stamp out rebelliousness.

The Ottoman Turks faced growing nationalist challenges in the Balkans. The Serbs revolted against Turkish rule and won virtual independence by 1817. A Greek general in the Russian army, Prince Alexander Ypsilanti, tried to lead a revolt against the Turks in 1820 but failed when the tsar, urged on by Metternich, disavowed him. Metternich feared rebellion even by Christians against their Turkish rulers. A second revolt, this time by Greek peasants, sparked a wave of atrocities in 1821 and 1822. The Greeks killed every Turk who did not escape; in retaliation, the Turks hanged the Greek patriarch of Constantinople and, in the areas they still controlled, pillaged churches, massacred thousands of men, and sold the women into slavery.

Western opinion turned against the Turks; Greece, after all, was the birthplace of Western civilization. While the great powers negotiated, Greeks and pro-Greece committees around the world sent food and military supplies; like the English poet Byron, a few enthusiastic European and American volunteers joined the Greeks. The Greeks held on until the great powers were willing to intervene. In 1827, a combined force of British, French, and Russian ships destroyed the Turkish fleet at Navarino Bay; and in 1828, Russia declared war on Turkey and advanced close to Constantinople. The Treaty of Adrianople of 1829 gave Russia a protectorate over the Danubian principalities in the Balkans and provided for a conference among representatives of Britain, Russia, and France, all of whom had broken with Austria in support of the Greeks. In 1830, Greece was declared an independent kingdom under the guarantee of the three powers; in 1833, the second son of King Ludwig of Bavaria became Otto I of Greece. Greek independence, supported by European public opinion, showed that Metternich’s systematic suppression of nationalism was reaching its limits.

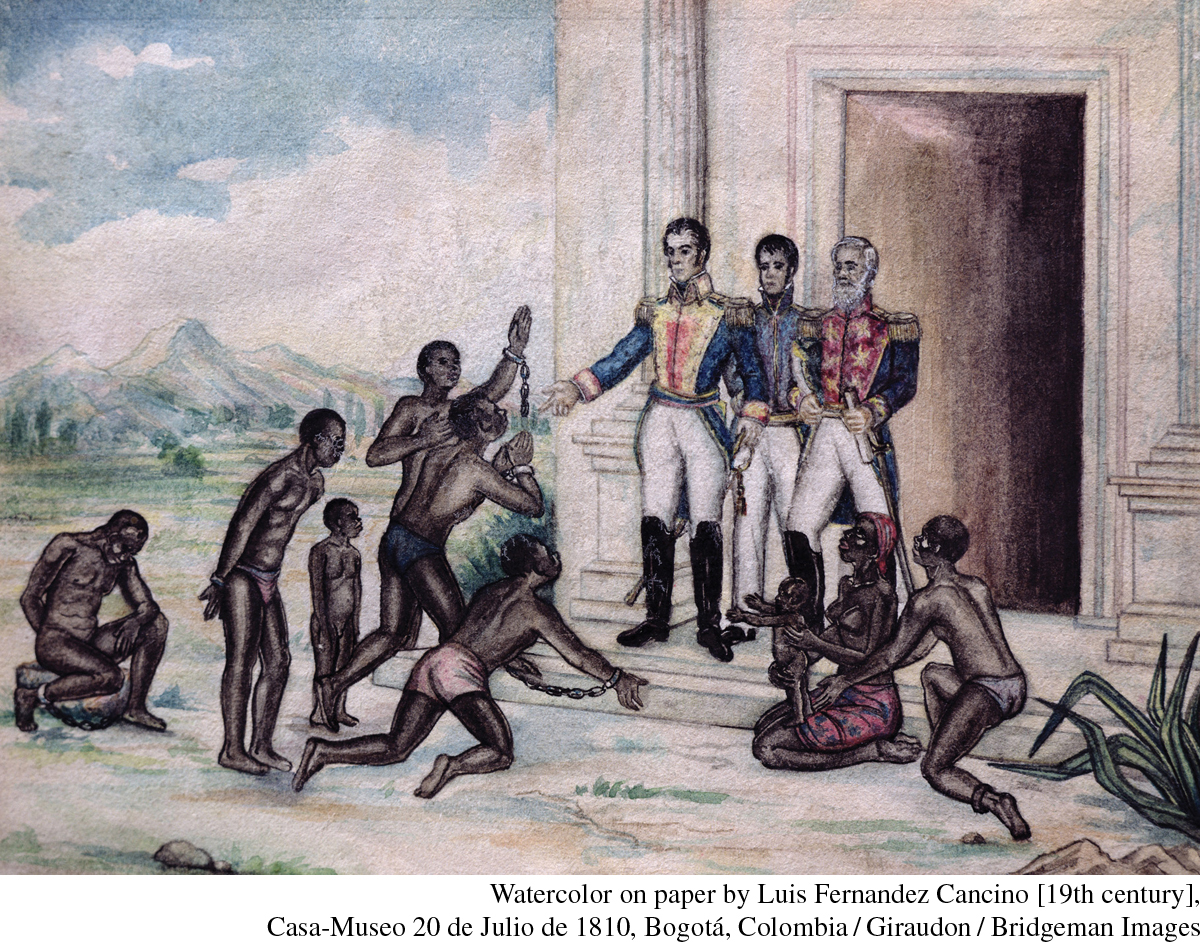

Across the Atlantic, national revolts also succeeded after a series of bloody wars of independence. Taking advantage of the upheavals in Spain and Portugal that began under Napoleon, restive colonists from Mexico to Argentina rebelled. One leader who stood out was Simón Bolívar (1783–1830), born in Caracas (present-day Venezuela) to an aristocratic slave-owning family of Spanish descent. He was educated in Europe on the works of Voltaire and Rousseau. Although Bolívar fancied himself a Latin American Napoleon, he had to acquiesce to the formation of a series of independent republics between 1821 and 1823, even in Bolivia, which is named after him.

By 1825, Portugal had lost all its American colonies, including Brazil, and Spain was left with only Cuba and Puerto Rico (Map 20.4). Brazil declared its independence under the banner of the Portuguese king’s own son and therefore maintained a monarchical form of government along with slavery. In contrast, the new republics freed those slaves who fought on their side, abolished the slave trade, and gradually eliminated slavery. The United States and Great Britain recognized the new states, and in 1823 U.S. president James Monroe announced his Monroe Doctrine, closing the Americas to European intervention—a prohibition that depended on British naval power and British willingness to declare neutrality.