Artistic Responses to Empire and Industry

Printed Page 765

Important EventsArtistic Responses to Empire and Industry

In the 1870s and 1880s, the arts explored the process of global expansion and economic innovation, often in the same gloomy Darwinistic terms that made reformers anxious. Darwin’s theory held out the possibility that strong civilizations, if they failed to adapt to changing conditions, could weaken and collapse. French writer Émile Zola, influenced by fears of social decay, had a dark vision of how industrial society affected individuals. He produced a series of novels set in industrializing France about a family plagued by alcoholism and madness. His characters led violent strikes and in one case even castrated an oppressive grocer. Zola’s novel Women’s Paradise (1883) depicts the upper-class shopper who abandons rational decision making as a consumer for the frenzy of the new department stores. Other fictional heroines were equally upsetting because they violated other long-standing rules. The character Nora in the drama A Doll’s House (1879), by Norwegian playwright Henrik Ibsen, undermines accepted values regarding the health of society by leaving an unsatisfying marriage. (See “Document 23.2: Henrik Ibsen, From A Doll’s House.”)

Some decorative arts of this period featured a countertrend that celebrated a healthy and heroic rural life away from stark realism. Country people used mass-produced textiles to create traditional-looking costumes and developed ceremonies based on a mythical past. Such invented customs, romanticized as old and authentic, brought tourists from the cities to villages. Urban architects and industrial designers copied rustic styles when creating household goods and decorative objects. The influence of empire is apparent in the traditional Persian and Indian motifs used by English designers William Morris (1834–1896) and his daughter May Morris (1862–1938) in their designs of fabrics, wallpaper, and household items based on such natural imagery as the silhouettes of plants. Their work gave birth to the arts and crafts style, whose “traditional” features paradoxically attracted consumers living in the modern industrial age.

Industrial developments directly influenced the work of painters, who by the 1870s felt intense competition from a popular industrial invention—the camera. Photographers could produce cheap copies of paintings and create more realistic portraits than painters could, at affordable prices. In response, painters altered their style, employing new and varying techniques to distinguish their art from the photographic realism of the camera. Claude Monet, for example, was fascinated by the way light transformed an object, and he often portrayed the same place—a bridge or a railroad station—at different times of day.

This daring style of art generally came to be called impressionism. It emphasizes the artist’s attempt to capture a single moment by focusing on the ever-changing light and color found in ordinary scenes. Using splotches and dots, impressionists moved away from the precise realism of earlier painters. Vincent Van Gogh used vibrant colors in great swirls to capture sunflowers, haystacks, and the starry evening sky. Closely following the impressionists, French painter Georges Seurat depicted with thousands of dots and dabs the Parisian suburbs’ newly created parks, with their Sunday bicyclists and office workers in their store-bought clothing, carrying books or newspapers. Industry contributed to the new styles of painting, as factories produced a range of pigments that allowed artists to use a wider and more intense spectrum of colors than ever before.

REVIEW QUESTION How did empire and industry influence art and everyday life?

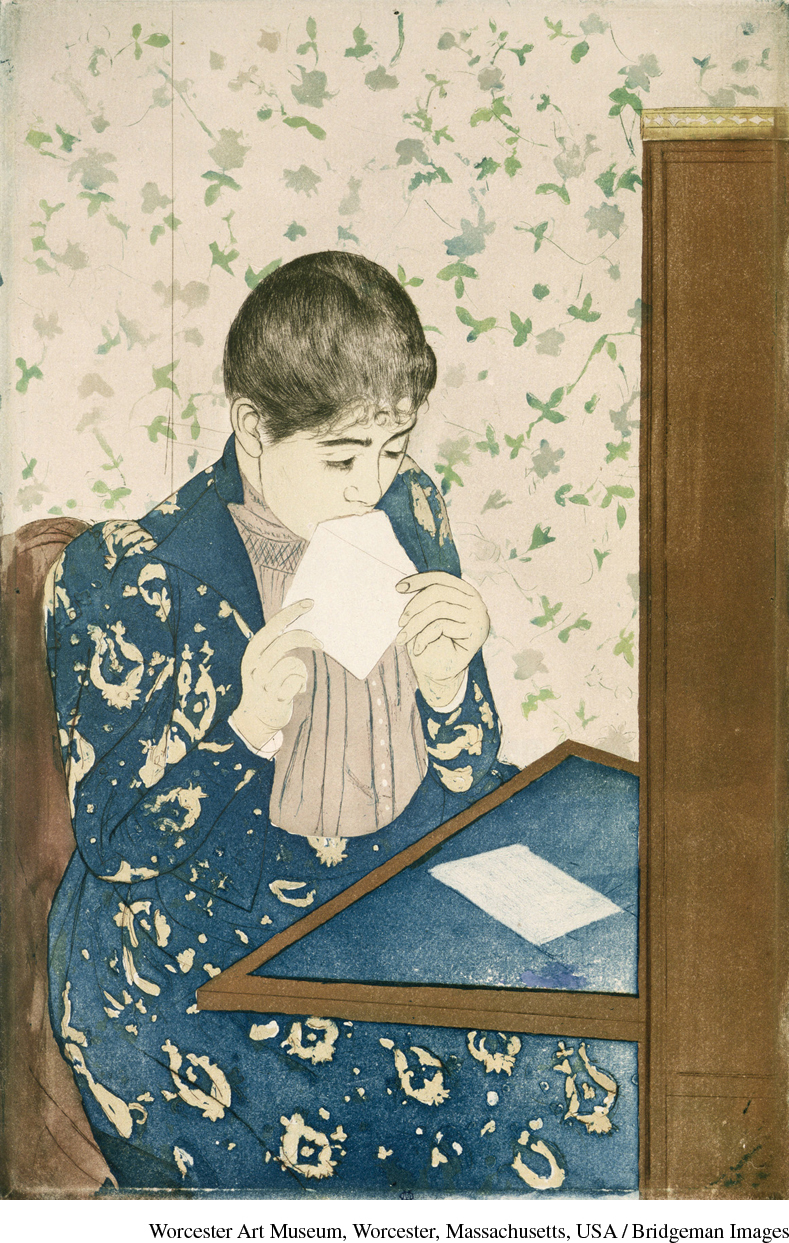

An increasingly global vision also influenced painting in the age of empire. In both composition and style, impressionists borrowed heavily from Asian art and architecture. The impressionist goal of portraying the fleetingness of light or human situations came from an ancient Japanese concept—mono no aware (“sensitivity to the fleetingness of life”). The color, line, and delicacy of Japanese art (which many impressionists collected) is evident, for example, in Monet’s later paintings of water lilies and even his re-creation of a Japanese garden at his home in France as the subject for artistic study. Similarly, the American expatriate Mary Cassatt used the two-dimensionality of Japanese art in The Letter (1890–1891) and other paintings. Van Gogh sometimes filled the background of portraits with copies of intensely colored Japanese prints, and in some paintings he imitated classic Japanese woodcuts. The graphic arts advanced the West’s ongoing borrowing from around the globe while responding to the changes brought about by industry.