The Paradoxes of Imperialism

Printed Page 752

Important EventsThe Paradoxes of Imperialism

Imperialism ignited constant, sometimes heated debate because of its many paradoxes. Although it was meant to make European nations more economically secure, imperialism intensified distrust in international politics as countries vied with one another for a share of world influence. In securing India’s borders, for example, the British faced Russian expansion in Afghanistan and along the borders of China, raising the costs of empire. Britain thus spent enormous amounts of tax revenue to maintain its empire even as its industrial lead began to slip. Yet for certain businesses, colonies provided crucial markets and large profits: late in the century, French colonies bought 65 percent of France’s exports of soap and 41 percent of its metallurgical exports. Imperialism provided huge numbers of jobs to people in European port cities, but taxpayers in all parts of a nation—whether they benefited or not—paid for colonial armies, increasingly costly weaponry, and administrators.

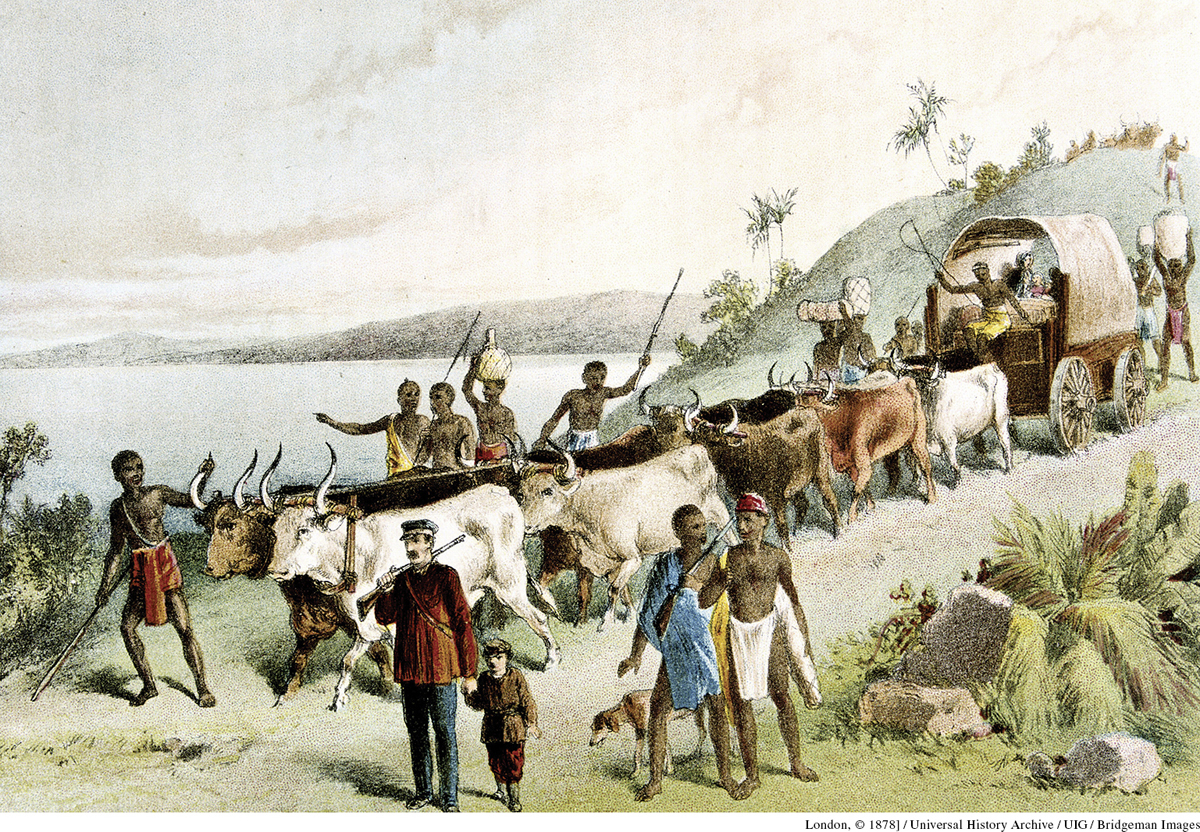

Advocates of imperialism pointed out that whites had a “civilizing mission.” The French thus taught some of their colonial subjects French language, literature, and history. In Germany’s African colonies, an exam for students in a school run by missionaries asked them to write on “Germany’s most important mountains” and “the reign of William I and the wars he waged.” The deeds of Africa’s great rulers and the accomplishments of its kingdoms disappeared from the curriculum. While Europeans believed in instructing colonial subjects, they did not believe that Africans and Asians were as capable as Europeans of great achievements.

Imperialism’s goal of “civilizing” was further conflicted. French advocates argued that their nation “must keep its role as the soldier of civilization.” But it was unclear whether imperialism should emphasize soldiering (that is, the conquest and murder of local peoples) or civilizing (the education of local peoples in the European tradition). Western scholars and travelers had long studied Asian and African languages, art, and literature, and had gathered and used botanical and other scientific knowledge. Yet appreciation of foreign cultures was tinged with bias and error. European scholars of Islam characterized Muhammad as an inferior imitation of Jesus, for example, and many Europeans stereotyped Asians and Africans as lying, lazy, self-indulgent, or irrational. One English official pontificated that “accuracy is abhorrent to the Oriental mind.” Such beliefs offered still another justification for conquest: that inferior colonized peoples would ultimately be grateful for what Europe had brought them.

European missionaries ventured to newly secured areas of Africa and Asia with attitudes similarly full of contradictions. A woman missionary reflected a common view when she remarked that the Tibetans with whom she worked were “going down, down into hell, and there is no one but me . . . to witness for Jesus amongst them.” Many people under colonial rule did accept Christianity, often blending their local religious practices with Christian ones. Christianizing entire populations proved impossible, especially when some imperial adventurers and soldiers became addicted, went mad, or were wantonly murdered. When native people resisted, missionaries often supported brutal military measures against them in the name of upholding Christian values and Western order.

REVIEW QUESTION What were the goals of the new imperialism, and how did Europeans accomplish those goals?

The paradoxes of imperialism are clear in hindsight, but at the time European self-confidence hid many of them. There was the belief that through imperialist ventures “a country exhibits before the world its strength or weakness as a nation,” as one French politician announced. Some in government, however, worried that imperialism—because of its expense and the constant possibility of war—might weaken rather than strengthen the nation-state. The most glaring paradox of all was that Western peoples who believed in nation building and national independence invaded the territory of others thousands of miles away and refused them the right to rule themselves.