Restoring Society

Printed Page 845

Important EventsRestoring Society

Civilians met the returning millions of brutalized, incapacitated, and shell-shocked veterans with combined joy and apprehension—and that apprehension was often valid. Tens of thousands of German, central European, and Italian soldiers refused to disband; some British veterans vandalized university classrooms and assaulted women streetcar conductors and factory workers. Many veterans were angry that civilians had protested wartime conditions instead of enduring them. Patriotic when the war erupted, civilians, especially women, sometimes felt estranged from the returning warriors who had inflicted so much death and who had lived daily with filth, rats, and decaying human flesh. While women who had served on the front had seen the soldiers’ suffering firsthand and could sympathize with them, many British suffragists, for instance, who had fought for equality in men’s and women’s lives before the war, now embraced separate spheres for men and women, so fearful were they of returning veterans.

For their part, veterans returned to a world that differed from the home they had left. They found that the war had blurred class distinctions, giving rise to expectations that life would be fairer afterward. Despite their expectations, veterans often had few or no jobs open to them, and some found that their wives and sweethearts had abandoned them. Many found, too, that women’s roles had gone through other changes: middle-class women did their own housework because former servants could earn more money in factories, and greater numbers of women worked outside the home. Women of all classes cut their hair short, wore sleeker clothes, smoked, and had money of their own because of war work.

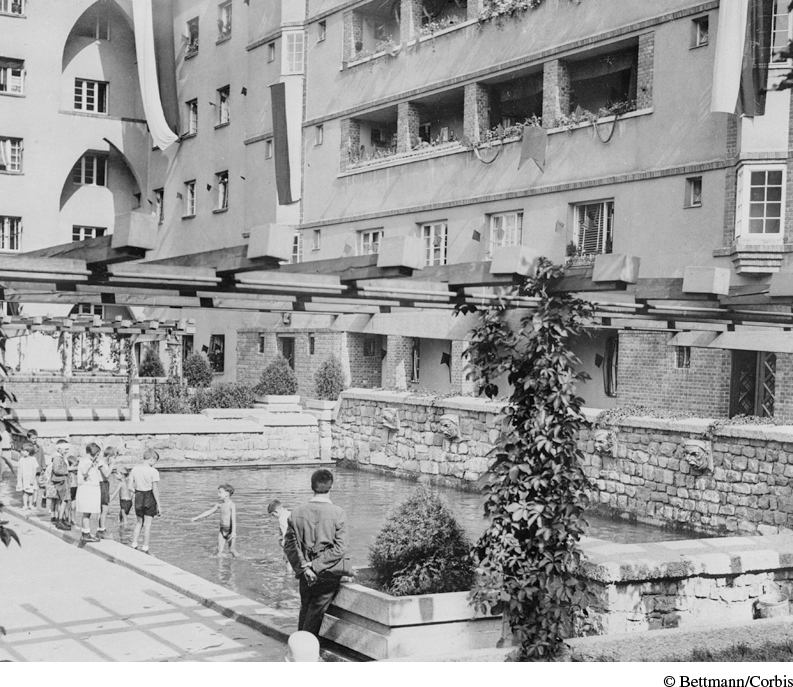

Focusing on veterans’ needs, governments tried to make civilian life as comfortable as possible to reintegrate men into society and reduce the appeal of communism. Politicians believed in the calming power of family life and supported social programs such as veterans’ pensions and housing and benefits for out-of-work men. The new housing—“homes for heroes,” as politicians called the program in Vienna, Frankfurt, Berlin, and Stockholm—provided common laundries, day-care centers, and rooms for socializing. Gardens, terraces, and balconies provided a soothing country ambience that offset the hectic nature of industrial life. Inside, they boasted modern kitchens and bathrooms, central heating, and electricity.

Despite government efforts to restore traditional family life, freer relationships and more open discussions of sex characterized the 1920s. Middle-class youths of both sexes visited jazz clubs and attended movies together. Revealing bathing suits, short skirts, and body-hugging clothing emphasized women’s sexuality, seeming to invite men and women to join together and replenish the postwar population. British scientist Marie Stopes published the best seller Married Love in 1918, and Dutch author Theodor van de Velde produced the wildly successful Ideal Marriage: Its Physiology and Technique in 1927. Both authors described sex in glowing terms and offered precise information about birth control and sexual physiology. One Viennese reformer promoted working-class marriage as “an erotic-comradely relationship of equals” rather than the economic partnership of past centuries. Meanwhile, such writers as the Briton D. H. Lawrence and the American Ernest Hemingway glorified men’s sexual vigor in, respectively, Women in Love (1920) and The Sun Also Rises (1926). Mass culture’s focus on heterosexuality encouraged the return to normality after the gender disorder that had troubled the prewar and war years.

As images of men and women changed, people paid more attention to bodily improvement. The increasing use of toothbrushes and toothpaste, safety and electric razors, and deodorants reflected new standards for personal hygiene and grooming. A multibillion-dollar cosmetics industry sprang up almost overnight. Women went to beauty parlors regularly to have their short hair cut, dyed, straightened, or curled. They also tweezed their eyebrows, applied makeup, and even submitted to cosmetic surgery. Ordinary women “painted” their faces (something only prostitutes had done formerly) and competed in beauty contests. Instead of wanting to look plump and pale, people aimed to become thin and tan, often through exercise and playing sports. Consumers’ new focus on personal health coincided with industry’s need for a physically fit workforce.

REVIEW QUESTION What were the major political, social, and economic problems facing postwar Europe, and how did governments attempt to address them?

As prosperity returned in the mid-1920s, people could afford to buy more consumer goods. Middle- and upper-class families snapped up sleek modern furniture, washing machines, and vacuum cleaners. Other modern conveniences such as electric irons and gas stoves appeared in better-off working-class households. Installment buying, popularized from the 1920s on, helped people finance these purchases. Family intimacy increasingly depended on machines of mass communication like radios, phonographs, and even automobiles, which not only transformed private life but also brought changes to the public world of mass culture and mass politics.