Cultural Debates over the Future

Printed Page 849

Important EventsCultural Debates over the Future

Cultural leaders in the 1920s either were obsessed with the horrendous experience of war or held high hopes for creating a fresh, utopian future that would have little relation to the past. German artists, especially, produced bleak or violent visions. The sculpture and woodcuts of German artist Käthe Kollwitz, whose son had died in the war, portrayed bereaved parents, starving children, and other heart-wrenching antiwar images (see the chapter-opening image). Others thought that Europeans needed to search for answers in far-off cultures. Seeing Europe as decadent, some turned to the spiritual richness of Asian philosophies and religions. An “Asiatic fever” seemed to grip intellectuals, including the British writer Virginia Woolf, who drew on ideas of reincarnation in her novel Orlando (1928), and the filmmaker Sergei Eisenstein, who modeled new techniques of film shots (montage) on Japanese calligraphy.

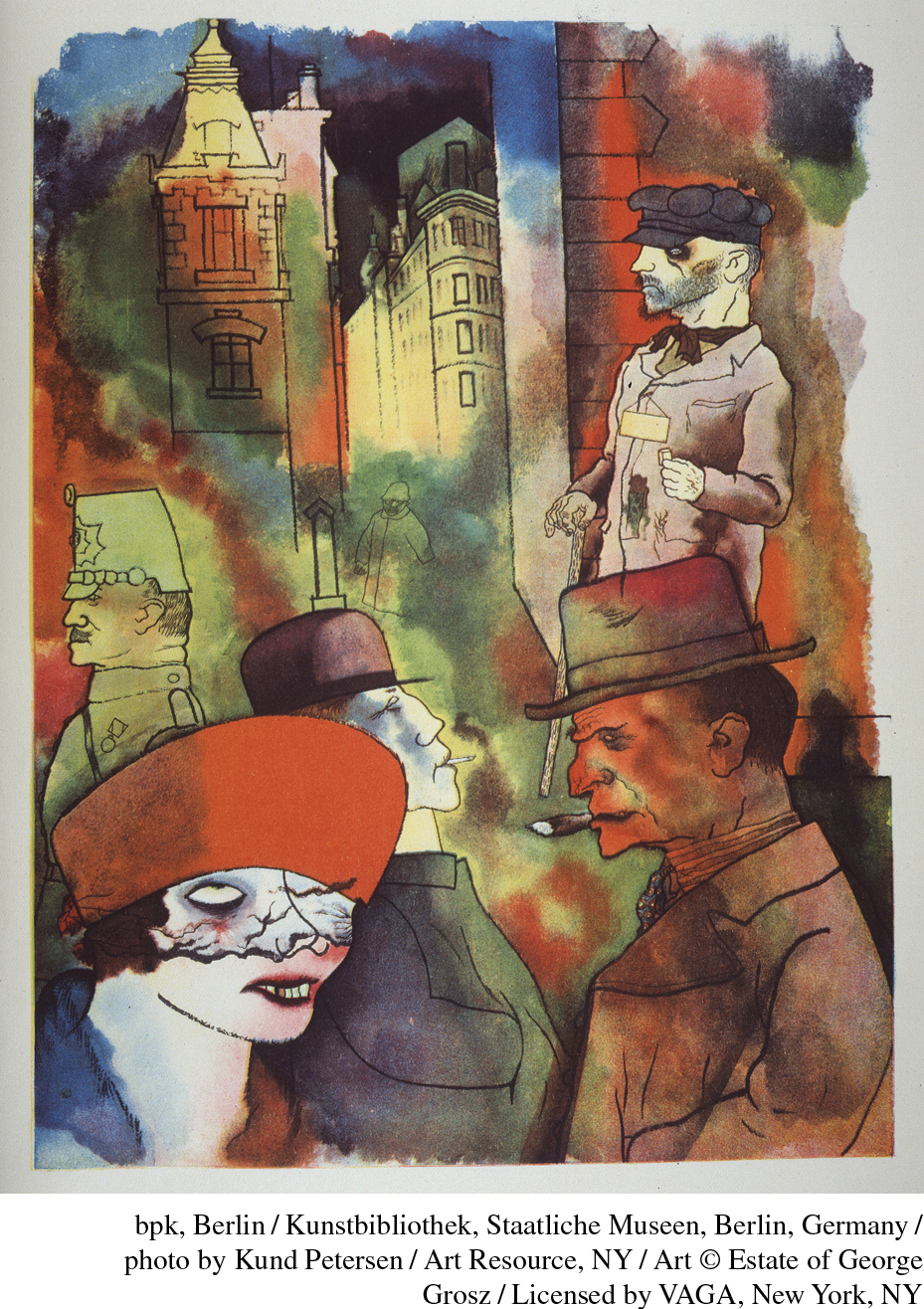

Other artists used satire and contempt to express postwar rage at civilization’s wartime failure. George Grosz (1893–1959), stunned by the war’s carnage, produced works marked by nonsense and shrieking expressions of alienation. Grosz’s paintings and cartoons of maimed soldiers and brutally murdered women reflected his self-proclaimed desire “to bellow back.” In the postwar years, the modernist practice of shocking audiences became more savage while portrayals of seedy everyday life flourished in cabarets and theaters in the 1920s and reinforced veterans’ beliefs in civilian decadence.

The art world itself became a battlefield, especially in defeated Germany, where it mirrored the Weimar Republic’s contentious politics. Popular writers such as veteran Ernst Jünger glorified life in the trenches and called for the militarization of society. In contrast, Erich Maria Remarque, also a veteran, cried out for an end to war in his controversial novel All Quiet on the Western Front (1928). This international best seller depicted the shared life of enemies on the battlefield, thus aiming to overcome the national hatred aroused by wartime propaganda. Remarque’s novel was part of a flood of popular, and often bitter, literature appearing on the tenth anniversary of the war’s end. It coincided with an interest in “Great War tourism” such as visiting battlefields. (See “Document 25.2: Memory and Battlefield Tourism.”)

The postwar arts produced many a utopian fantasy turned upside down; dystopias of life in a war-traumatized Europe multiplied. In the bizarre stories of Franz Kafka, who worked by day in a large insurance company in Prague, the world is a vast, impersonal machine. His novels The Trial (1925) and The Castle (1926) show the hopeless condition of individuals caught between the cogs of society’s relentlessly turning gears. His themes seemed to capture for civilian life the helplessness that soldiers had felt at the front. As the prewar way of life collapsed in the face of political and technological innovation, other writers depicted the complex, sometimes nightmarish inner life of individuals.

Irish writer James Joyce portrayed this interior self built on memories and sensations, many of them from the war. Joyce’s Ulysses (1922) illuminates the fast-moving inner lives of its characters in the course of a single day. In one of the most celebrated passages in Ulysses, a long interior monologue traces a woman’s lifetime of erotic and emotional sensations. The technique of using a character’s thoughts to propel a story was called stream of consciousness. Virginia Woolf, too, used this technique in her novel Mrs. Dalloway (1925). For Woolf, the war had dissolved the solid society from which absorbing stories and fascinating characters were once fashioned. Her characters experience fragmented conversations and incomplete relationships. Woolf’s novel Orlando also reflected the postwar attention to women. In the novel, the hero Orlando lives hundreds of years and in the course of his long life is eventually transformed into a woman.

There was another side to the postwar story, however—one based on the promise of technology. Before the war, avant-garde artists had celebrated the new, the futuristic, the utopian. After the war, like Jules Amar crafting prostheses for shattered limbs, many postwar artists were optimistic that technology could make an entire wounded society whole. The aim of art, observed one of them, “is not to decorate our life but to organize it.” German artists, calling themselves the Bauhaus (after the idea of a craft association, or Bauhütte), created streamlined office buildings and designed functional furniture and utensils, many of them inspired by forms from “untainted” East Asia and Africa. Russian artists, temporarily caught up in the communist experiment, optimistically wrote novels about cement factories and created ballets about steel.

Artists fascinated by technology and machinery were drawn to the most modern of all countries—the United States. Hollywood films, glossy advertisements, and the bustling metropolis of New York tempted careworn Europeans. They loved films about the Wild West or the supposedly carefree “modern girl.” They were especially attracted to jazz, the improvisational music developed by African Americans. Performers like Josephine Baker (1906–1975) and Louis Armstrong (1901–1971) became international sensations when they toured Europe’s capital cities. Like jazz, the New York skyscraper pointed to the future, not to the grim wartime past.