Seeing History: Portraying Soldiers in World War I

Printed Page 857

Important Events

During World War I, photography captured the reality of life for soldiers in the trenches and riveted the public’s attention. Because weaponry was so powerful, censorship in all combatant countries prevented the worst images—such as body parts lying around a battlefield or hanging from trees—from being printed. Some people created images that only suggested what war was like and tried to stir patriotism in heroic posters, while others, like Jules Amar, showed designs for prosthetics to add to veterans’ bodies. Soldiers themselves also portrayed life at the front in a variety of artistic ways.

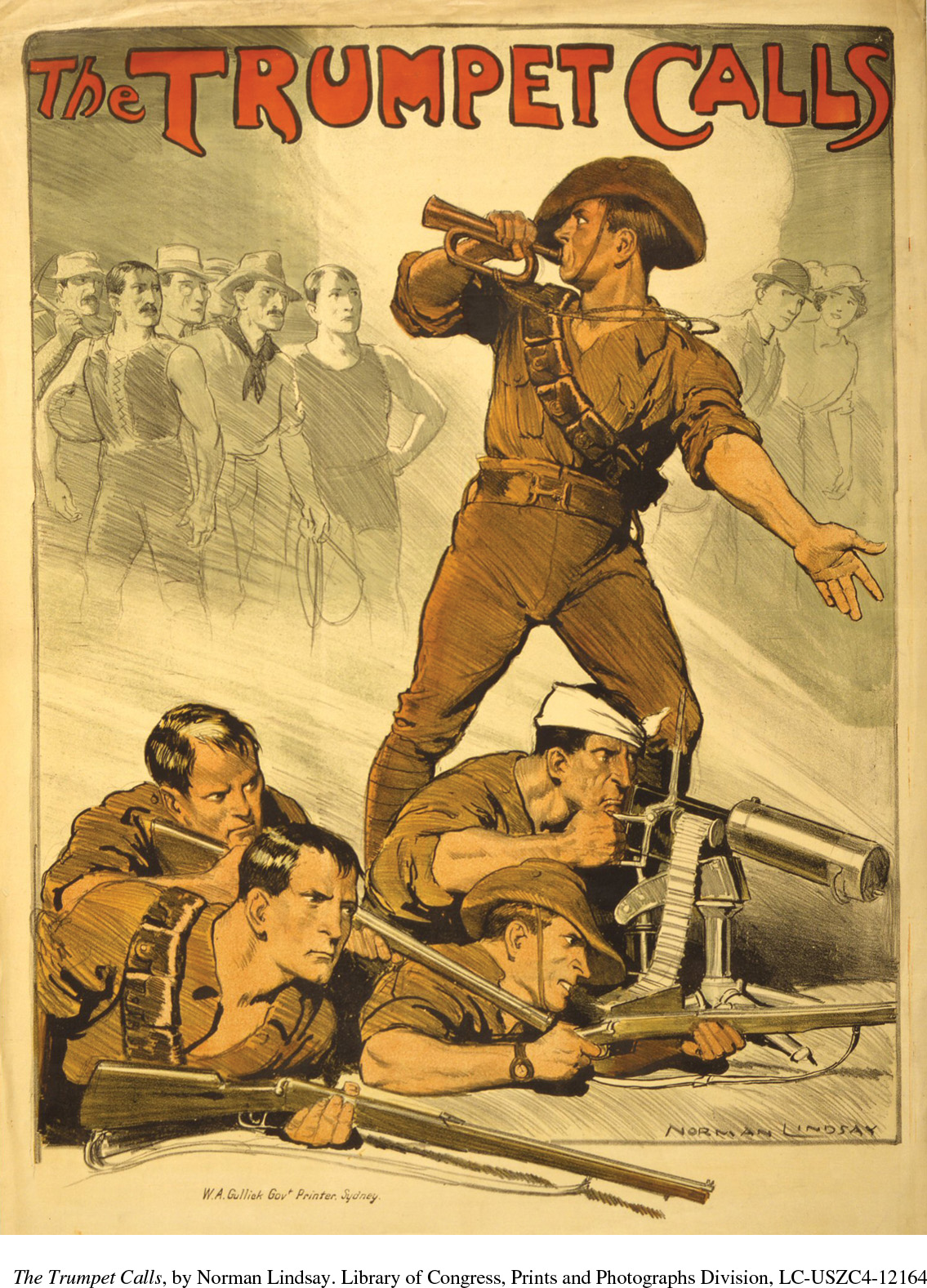

Visual propaganda was crucial in mobilizing civilian populations to join the military; work overtime on the home front; and willingly sacrifice food, health, and even their lives. Propaganda specialists who had promoted the arms buildups before the war now joined with graphic artists to produce emotionally compelling images, often of a savage enemy threatening helpless white women and their children. Celebrated Australian artist Norman Lindsay excelled in this genre as in others. The poster shown here, “The Trumpet Calls” (1918), suggested the transformation of ordinary men into muscular, brave soldiers. Indeed, Australian soldiers fought in large numbers in some of World War I’s most celebrated battles, including the battle of Gallipoli (1915), and, like soldiers from every country, became symbols of patriotism and national strength as a result.

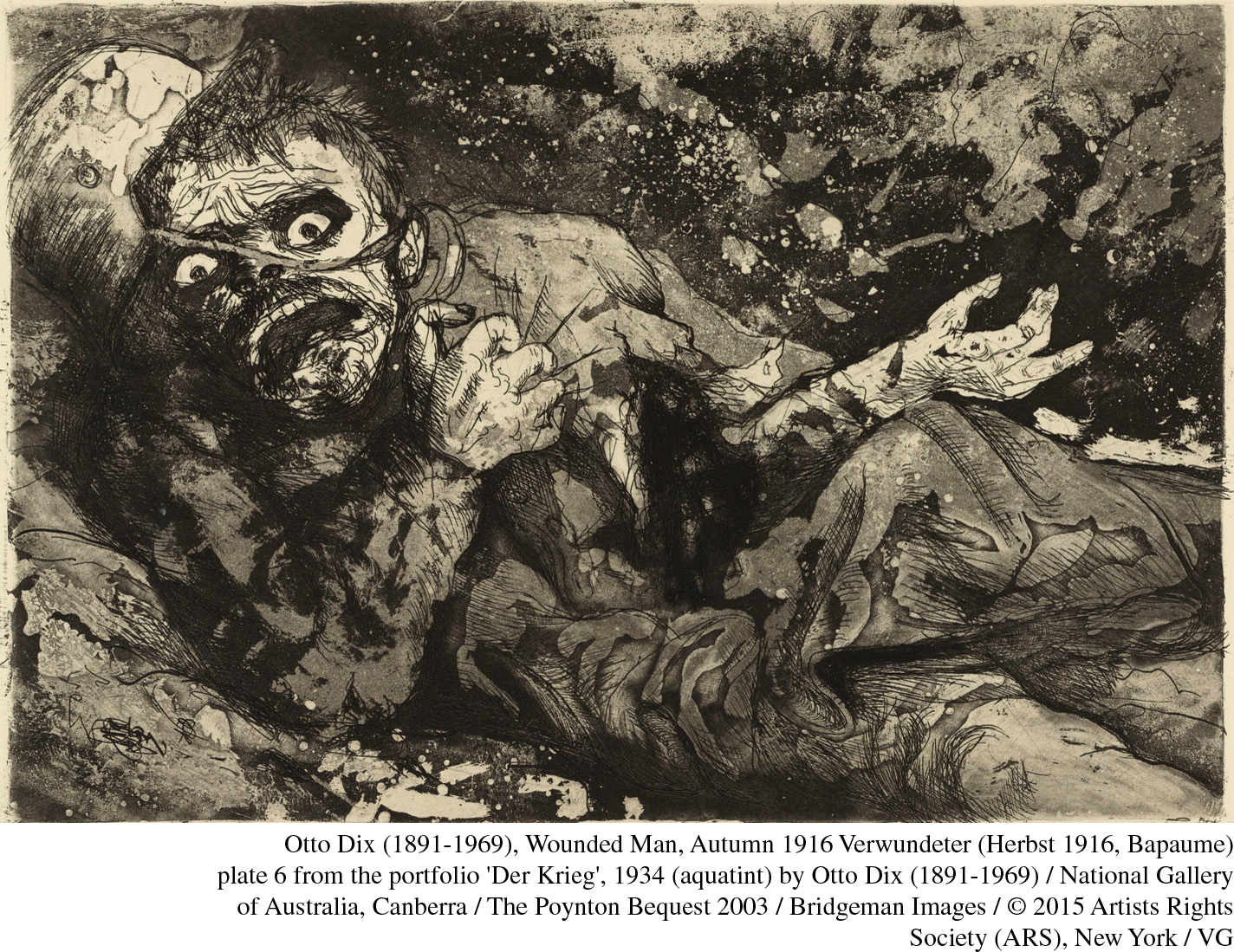

German artilleryman and artist Otto Dix was one of thousands of wartime volunteers, and his depictions of soldiers’ reality was starkly different. Asked why he had signed up for the war, he replied: “I had to experience how someone beside me suddenly falls over and is dead and the bullet has hit him squarely. I had to experience that quite directly. I wanted it. I’m therefore not a pacifist at all—or am I? Perhaps I was an inquisitive person.” His etching Wounded Soldier (completed in 1916 at the battle of the Somme and published in 1924) captures another side of war, one that many soldiers recalled in their postwar nightmares. Australian nurses described a similar reality for the wounded men in their diaries. As one put it more emotionally, “[I] shall not describe their wounds, they were too awful. One loses sight of all the honour and the glory in the work we are doing.” Another said that she only wished the wounded who would eventually die had been “killed outright,” so great was their agony. Competing visions of war shaped postwar culture and almost immediately influenced the course of politics.

Question to Consider

Compare these visual depictions of soldiers, the motivations that might have led to their production, and the effects they might have had on the viewing public. Which image do you think more powerful, and why?