Cold War Consumerism and Shifting Gender Norms

Printed Page 927

Important EventsCold War Consumerism and Shifting Gender Norms

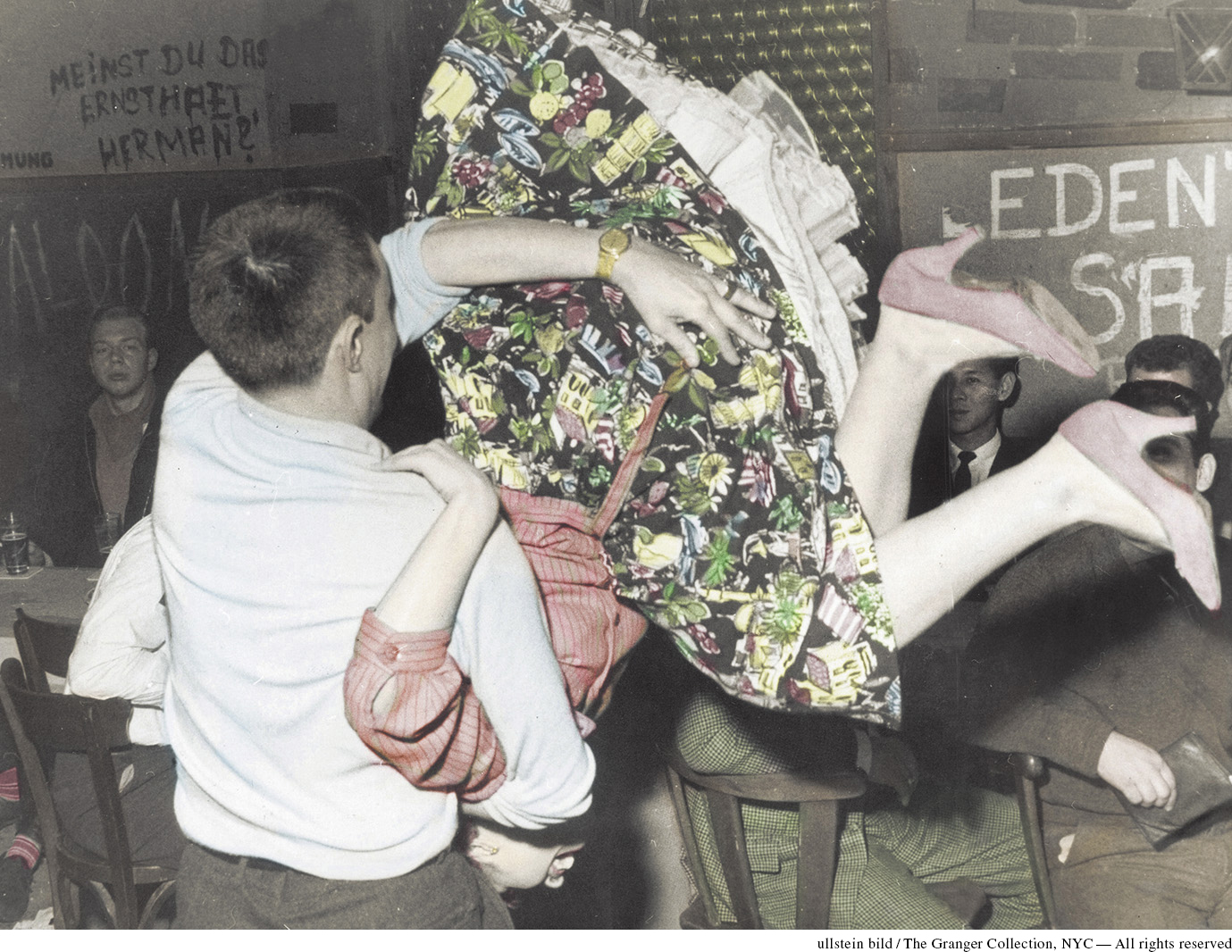

Government spending on Europe’s reconstruction and welfare after World War II helped prevent the kind of upheaval that had followed World War I. Meanwhile, the rising birthrate and bustling youth culture led to an upsurge in consumer spending that created jobs for veterans. Nonetheless, the war had affected men’s roles and sense of themselves. Young men who had missed World War II adopted the rough, violent style of soldiers, and roaming gangs posed as tough military types. While Soviet youth admired aviator aces, elsewhere groups such as the “teddy boys” in England (named after their Edwardian style of dressing) and the gamberros (“hooligans”) in Spain took their cues from pop culture in rock-and-roll music and film. (See “Document 27.3: Popular Culture, Youth Consumerism, and the Birth of the Generation Gap.”)

The leader of rock-and-roll style was the American singer Elvis Presley. Sporting slicked-back hair and an aviator-style jacket, Presley bucked his hips and sang sexual lyrics to screaming and devoted fans. Rock-and-roll concerts and movies galvanized youth across Europe, including the Soviet bloc, where teens demanded the production of blue jeans and leather jackets. In a German nightclub late in the 1950s, members of a British rock group of Elvis fans called the Quarrymen performed, yelling at and fighting with one another as part of their show. They would soon become known as the Beatles. Rebellious young American film stars like James Dean in Rebel Without a Cause (1955) created the beginnings of a postwar youth culture in which the ideal was to be a bad boy. The rebellious and rough masculine style appeared also in literature, for example in James Watson’s autobiography, The Double Helix (1968), in which he described how he and Francis Crick had discovered the structure of the DNA molecule by stealing other people’s findings. American “beat” poets and writers vehemently rejected the traditional ideals of the upright male breadwinner, family man, and responsible achiever. The 1953 inaugural issue of the American magazine Playboy, and the hundreds of magazines that imitated it across Europe, presented the modern man as sexually aggressive and independent of dull domestic life—just as he had been in the war. The definition of men’s citizenship had come to include not just political and economic rights but also sexual freedom outside the restrictions of marriage.

In contrast, Western society promoted a postwar model for women that differed from their wartime roles, adopting instead the fascist notion of women’s inferiority. Rather than being essential workers and heads of families in the absence of their men, postwar women were to symbolize the return to normalcy by leading a domestic and submissive life at home. Late in the 1940s, the fashion house of Christian Dior launched a clothing style called the “new look.” It featured pinched waists, tightly fitting bodices, and voluminous skirts. This restoration of the nineteenth-century female silhouette invited a renewal of clearly defined gender roles. Women’s magazines publicized the new look and urged women to give up ambitions for themselves. Even in the hard-pressed Soviet Union, domesticity flourished; recipes for homemade face creams, for example, passed from woman to woman, and beauty parlors did a brisk business. In the West, household products such as refrigerators and washing machines raised standards for housekeeping by giving women the means to be “perfect” housewives.

However, new-look propaganda did not necessarily mesh with reality or even with all social norms. Dressmaking fabric was still being rationed in the late 1940s; even in the next decade, women could not always get enough of it to make voluminous skirts. In Europe, where people had barely enough to eat, the underwear needed for new-look contours simply did not exist—although for many, unfortunately, the semistarved look was not achieved by choice. Moreover, European women continued to work outside the home after the war; indeed, mature women and mothers were working more than ever before—especially in the Soviet bloc. Across the Soviet sphere consumer goods were always in short supply, but opinion makers stressed to these women the importance of a tasteful and up-to-date domestic interior. East and West, the female workforce was going through a profound revolution as it gradually became populated by wives and mothers who would hold jobs all their lives despite being bombarded with images of nineteenth-century femininity.

The advertising business presided over the creation of these cultural messages as part of both the return of consumerism and the cold war. Guided by marketing experts, western Europeans imitated Americans by drinking Coca-Cola; using American detergents, toothpaste, and soap; and driving some forty million motorized vehicles, including motorbikes, cars, buses, and trucks. While many Europeans embraced American business practices, the cold war was ever present: the Communist Party in France led a successful campaign to ban Coca-Cola for a time in the 1950s, and tastemakers in the Soviet sphere initiated competing products and styles.

Radio remained the most influential medium in the 1950s, carrying much of the postwar consumer advertising and making the connection between cold war and consumerism. Even as the number of radios in homes grew steadily, television loomed on the horizon. In the United States, two-thirds of the population had TV sets in the early 1950s, while in Britain only one-fifth did. Only in the 1960s did television become an important consumer item for most Europeans. In radio and television, though, both East and West tried to exceed the other in advertising their values. Russian programs stressed a uniform Communist culture, often emphasizing the importance of family values and practical, if aesthetically pleasing, household tips for women. (See “Seeing History: The Soviet System and Consumer Goods.”) The United States, by contrast, promoted debate about current affairs and filled the airwaves with advertising for consumer goods. The cold war was thus a consumer as well as a military phenomenon.