Art, Ideas, and Religion in a Technocratic Society

Printed Page 947

Important EventsArt, Ideas, and Religion in a Technocratic Society

Cultural trends developed alongside the march of consumer society and technological breakthroughs. A new style in the visual arts was called pop art. It featured images from everyday life and employed the glossy techniques and products of what these artists called admass, or mass advertising. Like advertising itself, art leadership passed from Europe to the United States. U.S. pop artist Robert Rauschenberg, for example, made collages from comic strips, magazine clippings, and fabric to fulfill his vision that “a picture is more like the real world when it’s made out of the real world.” Maverick American artists such as Andy Warhol made pop art a financial success with their parodies of modern commercialism. Through images of actress Marilyn Monroe and former first lady Jacqueline Kennedy, Warhol showed, for example, how depictions of women were used to sell everything mass culture had to offer in the 1960s and 1970s. He portrayed Campbell’s soup cans as they appeared in advertisements and sold these works as elite artistic creations.

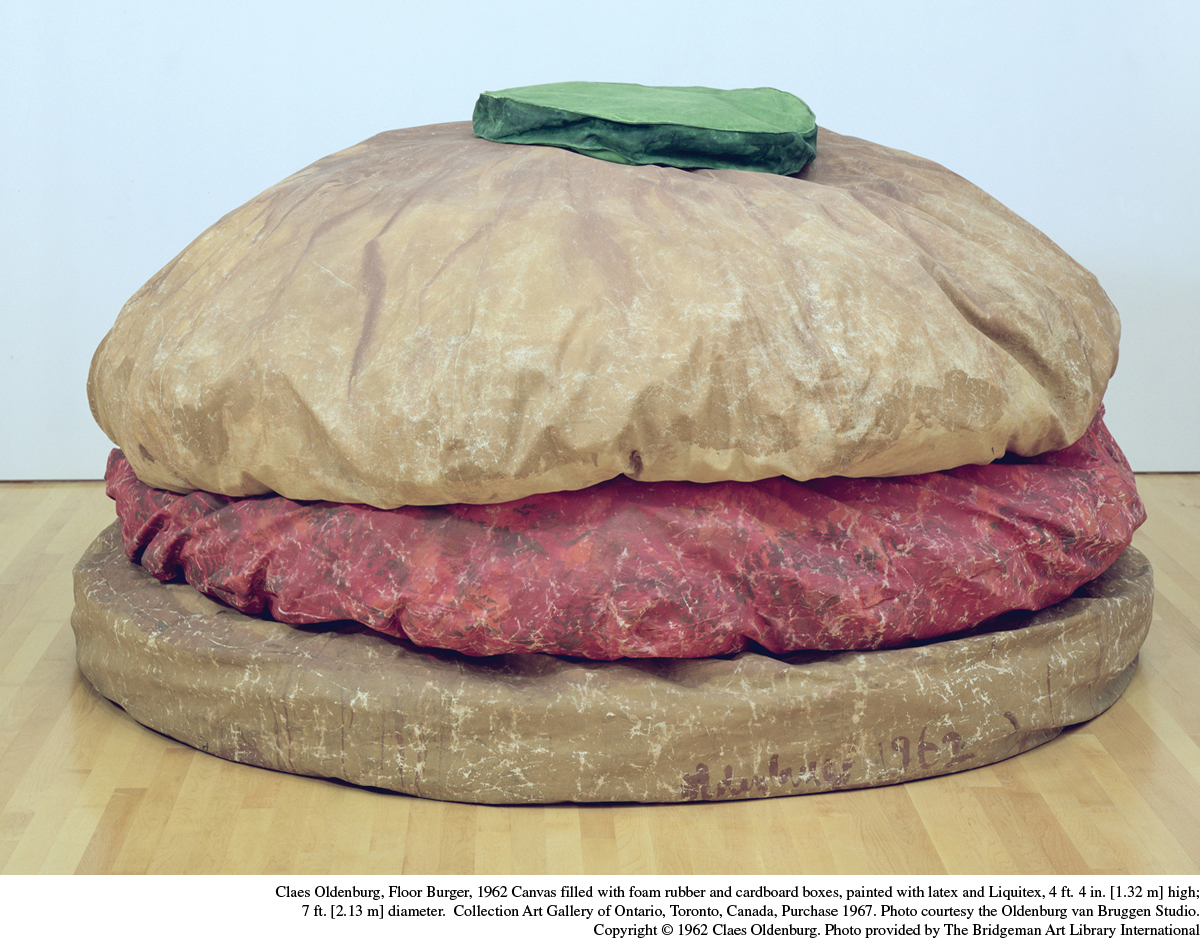

Swedish-born artist Claes Oldenburg portrayed the grotesque aspects of ordinary consumer products in Floor Burger (1962) and Lipstick Ascending on Caterpillar Tractor (1967). Capturing this mocking world of art, German artist Sigmar Polke did cartoon-like drawings of products and of those who craved them. The Swiss sculptor Jean Tinguely used rusted parts of old machines—the junk of industrial society—to make fountains that could move. His partner Niki de Saint Phalle then decorated them with huge, gaudy figures—many of them inspired by the folk traditions of the Caribbean and Africa. Their colorful, mobile fountains adorned main squares in Stockholm, Paris, and other cities.

The American composer John Cage worked in a similar vein when he added to his musical scores sounds produced by such everyday items as combs, pieces of wood, and radio noise. Buddhist influence led Cage to incorporate silence in music and to compose by randomly tossing coins and then choosing notes by the corresponding numbers in the ancient Chinese I Ching (Book of Changes). These techniques continued the trend away from classical melody that had begun with modernism. Other composers, called minimalists, simplified music by featuring repetition and sustained notes instead of producing the lush melodies of nineteenth-century symphonies and piano music. Estonian composer Arvo Pärt wrote minimalist pieces in the 1970s using only three or four notes in total; he called this style “starvation” music to emphasize the lack of both freedom and goods in the Soviet bloc. Improved recording technology and mass marketing brought music of all varieties to a wider home audience than ever before.

The social sciences reached the peak of their prestige in the postindustrial era, often because of the increasing use of statistical models made possible by advanced electronic computations. Anthropology was among the most exciting of the social sciences, for it brought young university students information about societies that seemed untouched by modern technology and industry. Colorful ethnographic films revealed different lifestyles and seemingly exotic practices. While studying people who came to be called “the other,” students had their sense of freedom reinforced by the vision of going back to nature. Whatever their discipline, social scientists announced that, like technicians and engineers, their specialized methods and factual knowledge were key to managing the complexities of postindustrial society and setting policy for developing nations.

At the same time, the social sciences undermined Enlightenment beliefs that individuals had true freedom. French anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss (1908–2009) developed a theory called structuralism, which insisted that all societies function within controlling structures—kinship, for example. While challenging existentialism’s claim that humans could create a free existence, structuralism also attacked the social sciences’ faith in rationality. Lévi-Strauss’s book The Savage Mind (1966) demonstrated that people outside the West, even though they did not use scientific methods, had their own effective systems of problem solving. In the 1960s and 1970s, the findings of some social scientists additionally echoed concerns that technology and highly managed bureaucratic systems were creating a society in which people lacked individuality and freedom.

REVIEW QUESTION How did Western society and culture change in the postindustrial age?

Religious leaders and parishioners responded to the changing times in a variety of ways. Pope Paul VI (r. 1963–1978) opposed artificial birth control as it became more prevalent, while also becoming the first pontiff to carry out the global vision of Vatican II by visiting Africa, Asia, and South America. In some places, grassroots religious fervor surged in the face of advancing science. Growing numbers of U.S. Protestants, for example, joined sects that denied the validity of scientific discoveries such as the age of the universe and the evolution of the species. In western Europe, however, Christian churchgoing remained at a low ebb. In the 1970s, for example, only 10 percent of the British population went to religious services—about the same number that attended live soccer matches. Most striking was the changing composition of the Western religious public, with immigration of people from former colonies and other parts of the world. Mosques, Buddhist temples, and shrines to other creeds appeared in a greater number of cities and towns.