Chapter Introduction

Independent

Assortment of Genes

CHAPTER

3

LEARNING OUTCOMES

After completing this chapter, you will be able to

In diploids, design experiments to make a dihybrid and then self-

or testcross it. In diploids, analyze the progeny phenotypes of dihybrid selfs and testcrosses and, from these results, assess whether the two genes are assorting independently (which would suggest locations of different chromosomes).

In haploids, design experiments to make a transient diploid dihybrid AaBb and analyze its haploid progeny to assess whether the two genes are assorting independently.

In crosses involving independently assorting dihybrids, predict the genotypic ratios in meiotic products, genotypic ratios in progeny, and phenotypic ratios in progeny.

Use chi-

square analysis to test whether observed phenotypic ratios are an acceptable fit to those predicted by independent assortment. In diploids, design experiments to synthesize lines that are pure-

breeding (homozygous) for two or more genes. Interpret two-

gene independent assortment ratios in terms of chromosome behavior at meiosis. Analyze progeny ratios of dihybrids in terms of recombinant frequency (RF) and apply the diagnostic RF for independent assortment.

Extend the principles of two-

gene independent assortment to heterozygotes for three or more genes. Extend the principle of independent assortment to multiple genes that each contribute to a phenotype showing continuous distribution.

Apply the diagnostic criteria for assessing whether mutations are in genes in cytoplasmic organelles.

This chapter is about the principles at work when two or more cases of single-

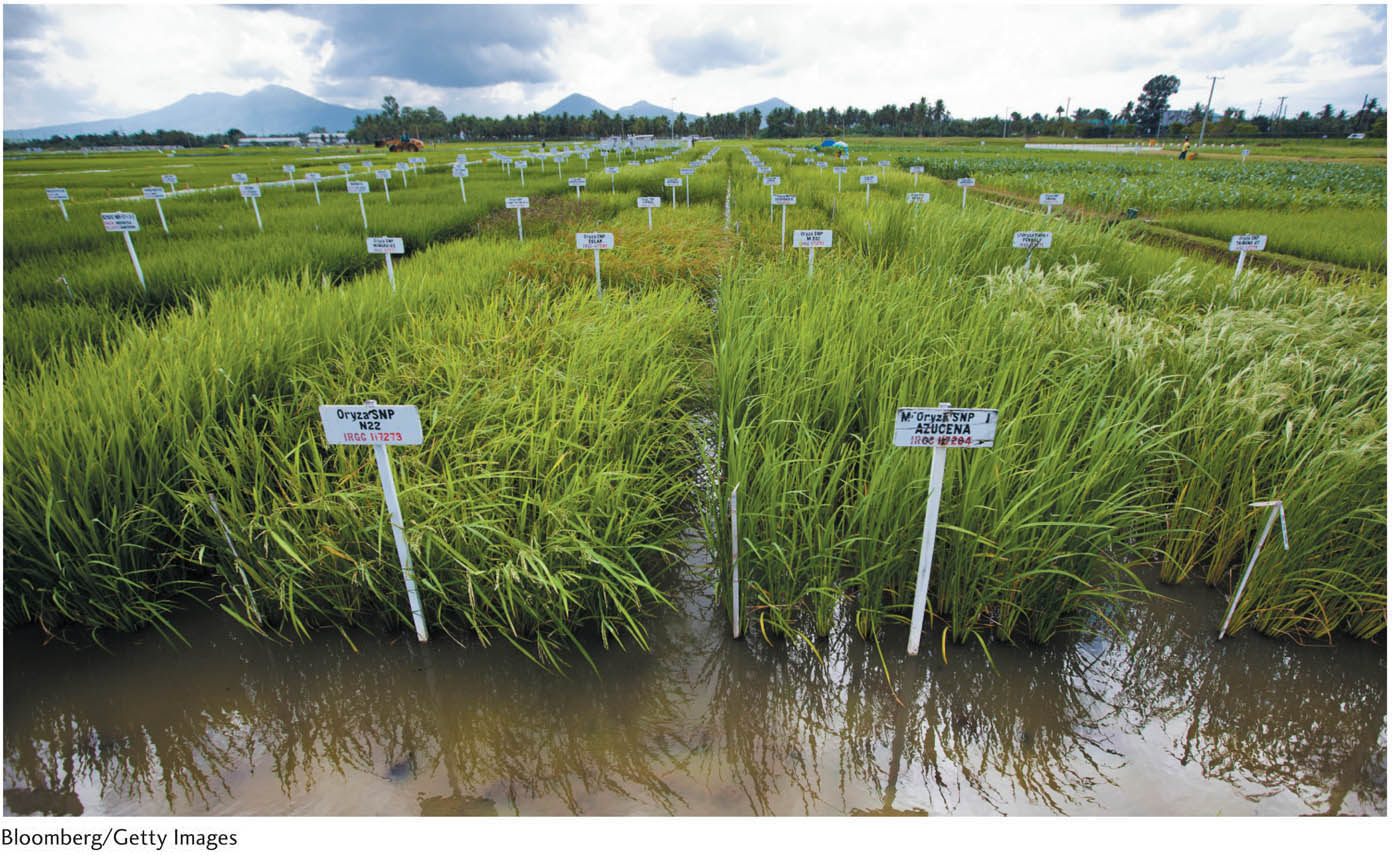

sd1. This recessive allele results in short stature, making the plant more resistant to “lodging,” or falling over, in wind and rain; it also increases the relative amount of the plant’s energy that is routed into the seed, the part that we eat.

se1. This recessive allele alters the plant’s requirement for a specific daylength, enabling it to be grown at different latitudes.

Xa4. This dominant allele confers resistance to the disease bacterial blight.

bph2. This allele confers resistance to brown plant hoppers (a type of insect).

Snb1. This allele confers tolerance to plant submersion after heavy rains.

To make a truly superior genotype, combining such alleles into one line is clearly desirable. To achieve such a combination, mutant lines must be intercrossed two at a time. For instance, a plant geneticist might start by crossing a strain homozygous for sd1 to another homozygous for Xa4. The F1 progeny of this cross would carry both mutations but in a heterozygous state. However, most agriculture uses pure lines, because they can be efficiently propagated and distributed to farmers. To obtain a pure-

This chapter explains how we can recognize independent assortment and how the principle of independent assortment can be used in strain construction, both in agriculture and in basic genetic research. (Chapter 4 covers the analogous principles applicable to heterozygous gene pairs on the same chromosome pair.)

We shall also see that independent assortment of an array of genes is also useful in providing a basic heritable mechanism for continuous phenotypes. These are properties such as height or weight that do not fall into distinct categories but are nevertheless often heavily influenced by multiple genes collectively called “polygenes.” We shall examine the role of independent assortment in the inheritance of continuous phenotypes influenced by such poly genes. We will see that independent assortment of polygenes can produce a continuous phenotypic distribution among progeny.

Lastly, we will introduce a different type of independent inheritance, that of genes in the organelles mitochondria and chloroplasts. Unlike nuclear chromosomes, these genes are inherited cytoplasmically and result in different patterns of inheritance than observed for nuclear genes and chromosomes. This pattern is independent of genes showing nuclear inheritance.

First, we examine the analytical procedures that pertain to the independent assortment of nuclear genes. These were first developed by the father of genetics, Gregor Mendel. So, again, we turn to his work as a prototypic example.