| Genetic "Vital Statistics" | |

|---|---|

|

Genome size: |

12 Mb |

|

Chromosomes: |

n = 16 |

|

Number of genes: |

6000 |

|

Percentage with human homologs: |

25% |

|

Average gene size: |

1.5 kb, 0.03 intron/gene |

|

Transposons: |

Small proportion of DNA |

|

Genome sequenced in: |

1996 |

Saccharomyces cerevisiae

Key organism for studying:

Genomics

Systems biology

Genetic control of cell cycle

Signal transduction

Recombination

Mating type

Mitochondrial inheritance

Gene interaction; two-

hybrid

The ascomycete S. cerevisiae, alias “baker’s yeast,” “budding yeast,” or simply “yeast,” has been the basis of the baking and brewing industries since antiquity. In nature, it probably grows on the surfaces of plants, using exudates as nutrients, although its precise niche is still a mystery. Although laboratory strains are mostly haploid, cells in nature can be diploid or polyploid. In approximately 70 years of genetic research, yeast has become “the E. coli of the eukaryotes.” Because it is haploid and unicellular, and forms compact colonies on plates, it can be treated in much the same way as a bacterium. However, it has eukaryotic meiosis, cell cycle, and mitochondria, and these features have been at the center of the yeast success story.

Special features

As a model organism, yeast combines the best of two worlds: it has much of the convenience of a bacterium, but with the key features of a eukaryote. Yeast cells are small (10 μm) and complete their cell cycle in just 90 minutes, allowing them to be produced in huge numbers in a short time. Like bacteria, yeast can be grown in large batches in a liquid medium that is continuously shaken. And, like bacteria, yeast produces visible colonies when plated on agar medium, can be screened for mutations, and can be replica plated. In typical eukaryotic manner, yeast has a mitotic celldivision cycle, undergoes meiosis, and contains mitochondria housing a small unique genome. Yeast cells can respire anaerobically by using the fermentation cycle and hence can do without mitochondria, allowing mitochondrial mutants to be viable.

Genetic analysis

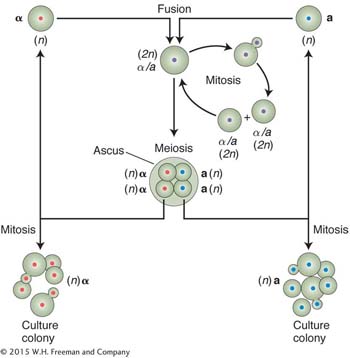

Performing crosses in yeast is quite straightforward. Strains of opposite mating type are simply mixed on an appropriate medium. The resulting a/α diploids are induced to undergo meiosis by using a special sporulation medium. Investigators can isolate ascospores from a single tetrad by using a machine called a micromanipulator. They also have the option of synthesizing a/a or α/α diploids for special purposes or creating partial diploids by using specially engineered plasmids.

Because a huge array of yeast mutants and DNA constructs are available within the research community, special-

The availability of both haploid and diploid cells provides flexibility for mutational studies. Haploid cells are convenient for large-

Life Cycle

Yeast is a unicellular species with a very simple life cycle consisting of sexual and asexual phases. The asexual phase can be haploid or diploid. A cell divides asexually by budding: a mother cell throws off a bud into which is passed one of the nuclei that result from mitosis. For sexual reproduction, there are two mating types, determined by the alleles MATα and MATa. When haploid cells of different mating type unite, they form a diploid cell, which can divide mitotically or undergo meiotic division. The products of meiosis are a nonlinear tetrad of four ascospores.

Total length of life cycle: 90 minutes to complete cell cycle

Techniques of Genetic Manipulation

|

Standard mutagenesis: |

|

|

Chemicals and radiation |

Random somatic mutations |

|

Transposons |

Random somatic insertions |

|

Transgenesis: |

|

|

Integrative plasmid |

Inserts by homologous recombination |

|

Replicative plasmid |

Can replicate autonomously (2μ or ARS origin of replication) |

|

Yeast artificial chromosome |

Replicates and segregates as a chromosome |

|

Shuttle vector |

Can replicate in yeast or E. coli |

|

Targeted gene knockouts: |

|

|

Gene replacement |

Homologous recombination replaces wild- |

Genetic engineering

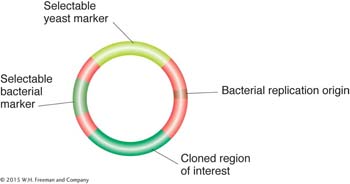

Transgenesis. Budding yeast provides more opportunities for genetic manipulation than any other eukaryote (see Chapter 10). Exogenous DNA is taken up easily by cells whose cell walls have been partly removed by enzyme digestion or abrasion. Various types of vectors are available. For a plasmid to replicate free of the chromosomes, it must contain a normal yeast replication origin (ARS) or a replication origin from a 2-

A simple yeast vector. This type of vector is called a yeast integrative plasmid (YIp).

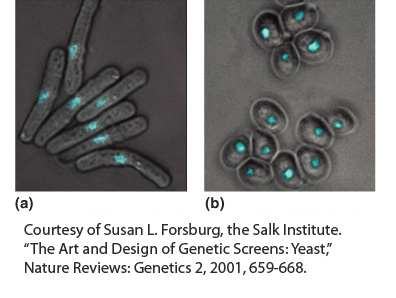

Targeted knockouts. Transposon mutagenesis (transposon tagging) can be accomplished by introducing yeast DNA into E. coli on a shuttle vector; the bacterial transposons integrate into the yeast DNA, knocking out gene function. The shuttle vector is then transferred back into yeast, and the tagged mutants replace wild-

Main contributions

Thanks to a combination of good genetics and good biochemistry, yeast studies have made substantial contributions to our understanding of the genetic control of cell processes.

Cell cycle. The identification of cell-

Recombination. Many of the key ideas for the current molecular models of crossing over (such as the double-

Gene interactions. Yeast has led the way in the study of gene interactions. The techniques of traditional genetics have been used to reveal patterns of epistasis and suppression, which suggest gene interactions (see Chapter 6). The two-

Mitochondrial genetics. Mutants with defective mitochondria are recognizable as very small colonies called “petites.” The availability of these petites and other mitochondrial mutants enabled the first detailed analysis of mitochondrial genome structure and function in any organism.

Genetics of mating type. Yeast MAT alleles were the first mating-

Other areas of contribution

Genetics of switching between yeast-

like and filamentous growth Genetics of senescence