Culture Region

Culture Region

culture region A geographical unit based on characteristics and functions of culture.

Phrased as a question, the theme of culture region could be “How are people and their traits grouped or arranged geographically?” Places and regions provide the essence of geography. How and why are places alike or different? How do they mesh together into functioning spatial networks? How do their inhabitants perceive them and identify with them? These are central geographical questions. A culture region is a grouping of similar places or the functional union of places to form a spatial unit.

Maps provide an essential tool for describing and revealing culture regions. If, as is often said, one picture is worth a thousand words, then a well-prepared map is worth at least 10,000 words to the geographer. No description in words can rival a map’s revealing force. Maps are valuable tools particularly because they so concisely portray spatial patterns in culture.

Geographers recognize three types of regions: formal, functional, and vernacular.

Formal Culture Regions

Formal Culture Regions A formal culture region is an area inhabited by people who have one or more traits in common, such as language, religion, or a system of livelihood. It is an area, therefore, that is relatively homogeneous with regard to one or more cultural traits. Geographers use this concept to map spatial differences throughout the world. For example, an Arabic-language formal region can be drawn on a map of languages and would include the areas where Arabic is spoken, rather than, say, English or Hindi or Mandarin. Similarly, a wheat-farming formal region would include the parts of the world where wheat is a major crop (look again at Figure 1.2).

formal culture region A cultural region inhabited by people who have one or more cultural traits in common.

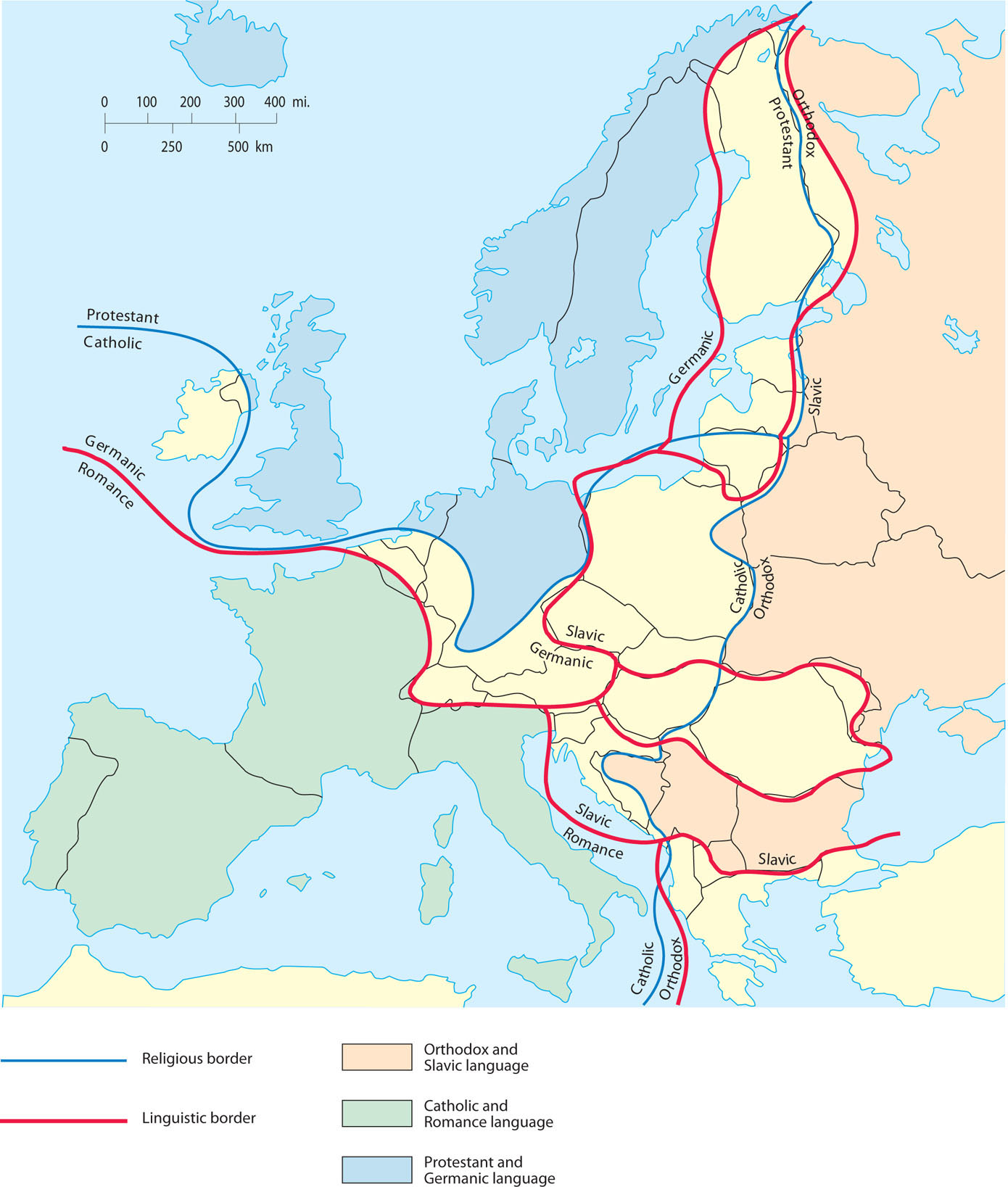

The examples of Arabic speech and of wheat cultivation represent the concept of formal culture region at its simplest level. Each is based on a single cultural trait. More commonly, formal culture regions depend on multiple related traits (Figure 1.3). Thus, an Inuit (Eskimo) culture region might be based on language, religion, economy, social organization, and type of dwellings. The region would reflect the spatial distribution of these five Inuit cultural traits. Districts in which all five of these traits are present would be part of the culture region. Similarly, Europe can be subdivided into several multitrait regions (Figure 1.4).

Thinking Geographically

Question

What evidence suggests changes in this region?

Thinking Geographically

Question

What does this teach us about boundaries between cultures?

5

Formal culture regions are the geographer’s somewhat arbitrary creations. No two cultural traits have the same distribution, and the territorial extent of a culture region depends on what and how many defining traits are used (see Figure 1.4). Why five Inuit traits, not four or six? Why not foods instead of (or in addition to) dwelling types? Consider, for example, Greeks and Turks, who differ in language and religion. Formal regions defined on the basis of speech and religious faith would separate these two groups. However, Greeks and Turks hold many other cultural traits in common. Both groups are monotheistic, worshipping a single god. In both groups, male supremacy and patriarchal families are the rule. Both enjoy certain folk foods, such as shish kebab. Whether Greeks and Turks are placed in the same formal region or in different ones depends entirely on how the geographer chooses to define the region. That choice in turn depends on the specific purpose of research or teaching that the region is designed to serve. Thus, an infinite number of formal regions can be created. It is unlikely that any two geographers would use exactly the same distinguishing criteria or place cultural boundaries in precisely the same location.

6

border zone The area where different regions meet and sometimes overlap.

core-periphery A concept based on the tendency of both formal and functional culture regions to consist of a core, in which defining traits are purest or functions are headquartered, and a periphery that is tributary and displays fewer of the defining traits.

The geographer who identifies a formal region must locate borders. Because cultures overlap and mix, such boundaries are rarely sharp, even if only a single cultural trait is mapped. For this reason, we find border zones rather than lines. These zones broaden with each additional trait that is considered because no two traits have the same spatial distribution. As a result, instead of having clear borders, formal regions reveal a center or core where the defining traits are all present. Moving away from the central core, the characteristics weaken and disappear. Thus, many formal regions display a core-periphery pattern in which the region can be divided into two sections, one near the center, where the particular attributes that define the region (in this case, language and religion) are strong, and other portions of the region farther away from the core, called the periphery, where those attributes are weaker.

In a real sense, then, the human world is chaotic. No matter how closely related two elements of culture seem to be, careful investigation always shows that they do not cover exactly the same area. This is true regardless of what degree of detail is involved. What does this chaos mean to cultural geographers? First, it tells us that every cultural trait is spatially unique and that the explanation for each spatial variation differs in some degree from all others. Second, it means that culture changes continually throughout an area and that every inhabited place on Earth has a unique combination of cultural features. No place is exactly like another.

Does this cultural uniqueness of each place prevent geographers from seeking explanatory theories? Does it doom them to explaining each locale separately? The answer must be no. The fact that no two hills or rocks, no two planets or stars, no two trees or flowers are identical has not prevented geologists, astronomers, and botanists from formulating theories and explanations based on generalizations.

Functional Culture Regions

functional culture region A cultural area that functions as a unit politically, socially, or economically.

node A central point in a functional culture region where functions are coordinated and directed.

Functional Culture Regions The hallmark of a formal culture region is cultural homogeneity. Moreover, it is abstract rather than concrete. By contrast, a functional culture region need not be culturally homogeneous; instead, it is an area that has been organized to function politically, socially, or economically as one unit. A city, an independent state, a precinct, a church diocese or parish, a trade area, a farm, and a Federal Reserve Bank district are all examples of functional culture regions. Functional culture regions have nodes, or central points where the functions are coordinated and directed. Examples of such nodes are city halls, national capitals, precinct voting places, parish churches, factories, and banks. In this sense, functional regions also possess a core-periphery configuration in common with formal culture regions.

7

Many functional regions have clearly defined borders. A metropolitan area is a functional region that includes all of the land under the jurisdiction of a particular urban government (Figure 1.5). The borders of this functional region may not be so apparent from a car window, but they will be clearly delineated on a regional map by a line distinguishing one jurisdiction from another. Similarly, each state in the United States and each Canadian province is a functional region, coordinated and directed from a capital, with government control extended over a fixed area with clearly defined borders.

Thinking Geographically

Question

Can you identify the border of this functional region? Why or why not?

Not all functional regions have fixed, precise borders, however. A good example is a daily newspaper’s circulation area. The node for the paper is the plant where it is produced. Every morning, trucks move out of the plant to distribute the paper throughout the city. The newspaper may have a sales area extending into the city’s suburbs, local bedroom communities, nearby towns, and rural areas. There its sales area overlaps with the sales territories of competing newspapers published in other cities. It would be futile to try to define exclusive borders for such an area. How would you draw a sales area boundary for The New York Times? Its Sunday edition is sold in some quantity even in California, thousands of miles from its node, and it is published simultaneously in different cities.

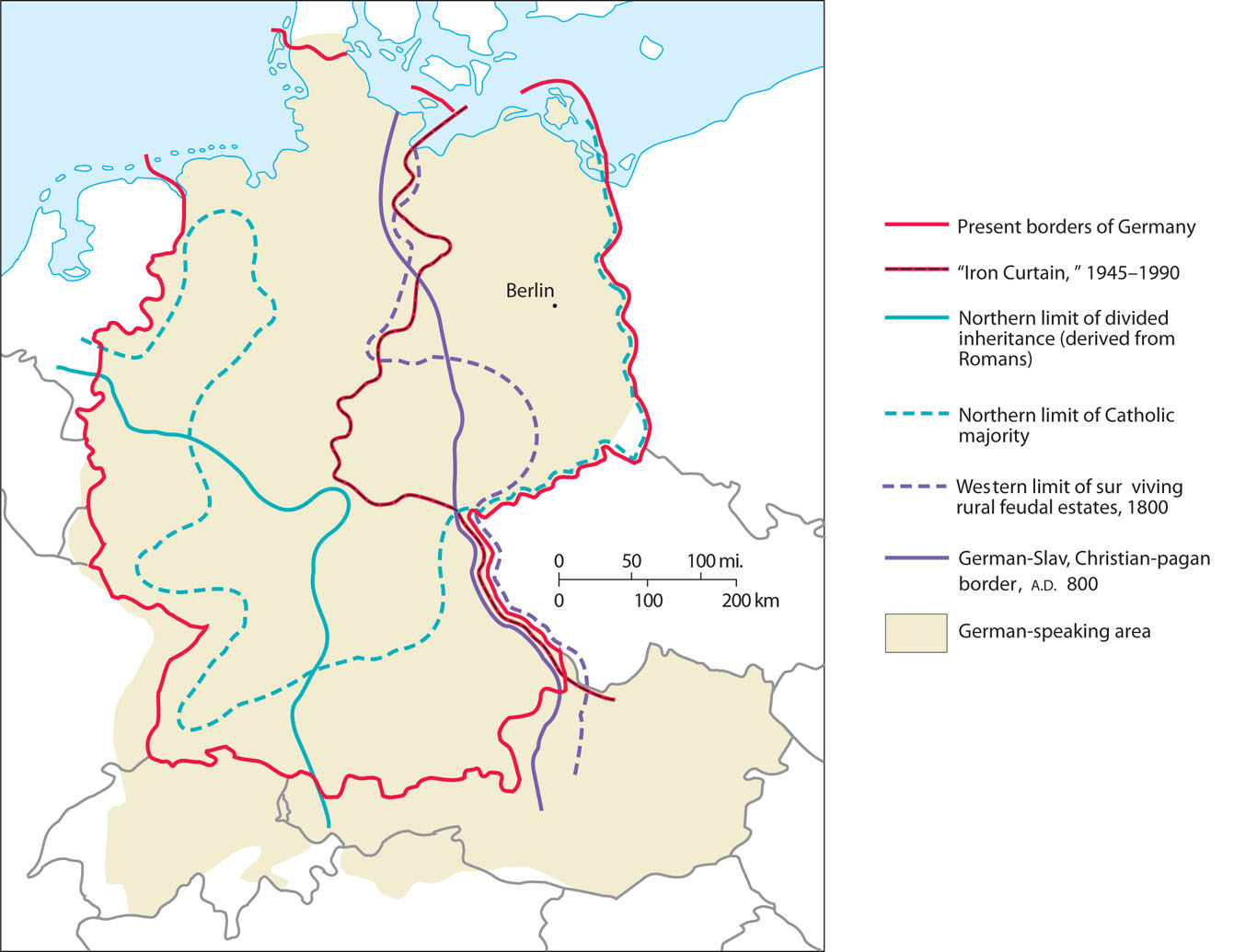

Functional culture regions generally do not coincide spatially with formal regions, and this disjuncture often creates problems for the functional region. Germany provides an example (Figure 1.6). As an independent state, Germany forms a functional region. Language provides a substantial basis for political unity. However, the formal region of the German language extends beyond the political borders of Germany and includes part or all of eight other independent states. More important, numerous formal regions have borders cutting through German territory. Some of these have endured for millennia, causing differences among northern, southern, eastern, and western Germans. These contrasts make the functioning of the German state more difficult and help explain why Germany has been politically fragmented more often than unified.

Thinking Geographically

Question

How might these sectional contrasts cause problems for modern Germany?

8

Vernacular Culture Regions

Vernacular Culture Regions A Vernacular Culture Region is one that is perceived to exist by its inhabitants, as evidenced by the widespread acceptance and use of a special regional name. Some vernacular culture regions are based on physical environmental features. For example, there are many regions called simply “the valley.” Wikipedia lists more than 30 different regions within the United States and Canada that are referred to as such, places as varied as the Sudbury Basin in Ontario and the Lehigh Valley in Pennsylvania. In the 1980s, “the valley” became synonymous with the San Fernando Valley in Southern California (Figure 1.7) and became associated with a type of landscape (suburban), a person (a white, teenage girl, called the “valley girl”), and a way of speaking (“Valspeak”).

Thinking Geographically

Question

Can you think of other examples of regions that are locally known as “the valley”?

vernacular culture region A cultural region perceived to exist by its inhabitants; based in the collective spatial perception of the population at large; bearing a generally accepted name or nickname (such as Dixie).

Examples of vernacular regions based on physical environmental features can be found outside of the United States and Canada as well. One such example is the Outback in Australia. For most people, “the Outback” conjures images of a wild and rugged place dominated by rocky red soil, exotic wildlife, and the majestic Uluru (or Ayers Rock) (Figure 1.8). This vernacular region loosely corresponds to certain climate zones, soil types, and terrain features. However, like other vernacular regions, the Outback is based more on popular perception than on these physical characteristics. Images of the Outback as a frontier, created in fiction and films like Crocodile Dundee, have generated a host of pop culture phenomena including foods (for example, “shrimp on the barbie”), clothing styles, and even well-known phrases like “G’day, mate!” Another global example of a vernacular region is the Riviera on the sunny northwest coast of the Mediterranean Sea (Figure 1.9). Although this region corresponds loosely to a particular climatic zone, it is imagined by most people as a region of affluence featuring yachts, casinos, and royalty.

Thinking Geographically

Question

Can you think of other vernacular regions based on physical environmental characteristics that are similar to the Outback in terms of their reputation for being a “rugged frontier”?

Thinking Geographically

Question

How do you think perceptions of the Riviera might differ between people who live or vacation there and people in the rest of the world?

Other vernacular culture regions find their basis in economic, political, or historical characteristics. Vernacular regions, like most regions, generally lack sharp borders, and the inhabitants of any given area may claim residence in more than one such region. They vary in scale from city neighborhoods to sizable parts of continents.

9

At a basic level, the vernacular culture region grows out of people’s sense of belonging and identification with a particular region. By contrast, many formal or functional culture regions lack this attribute and, as a result, are often far less meaningful for people. You’re more likely to hear people say, “we’re fighting to preserve ‘the valley’ from further urban development,” than to see people rally under the banner of “wheat-growing areas of the world!” Self-conscious regional identity can have major political and social ramifications.

Vernacular culture regions often lack the organization necessary for functional regions, although they may be centered on a single urban node, and they frequently do not display the cultural homogeneity that characterizes formal regions.

10