Folk and Popular Culture Regions

Folk and Popular Culture Regions

How do cultures vary geographically? Some cultures exhibit major material and nonmaterial variations from place to place with minor variations over time. Others display less difference from region to region but change rapidly over time. For this reason, the theme of culture region is particularly well suited to the study of cultural difference. Formal culture regions can be delineated on the basis of both material and nonmaterial elements.

Material Folk Culture Regions

Material Folk Culture Regions

Although folk culture has largely vanished from the United States and Canada, vestiges remain in various areas of both countries. Figure 2.1 shows culture regions in which the material artifacts of 13 different North American folk cultures survive in some abundance, but even these artifacts are disappearing. Each region possesses many distinctive relics of material culture.

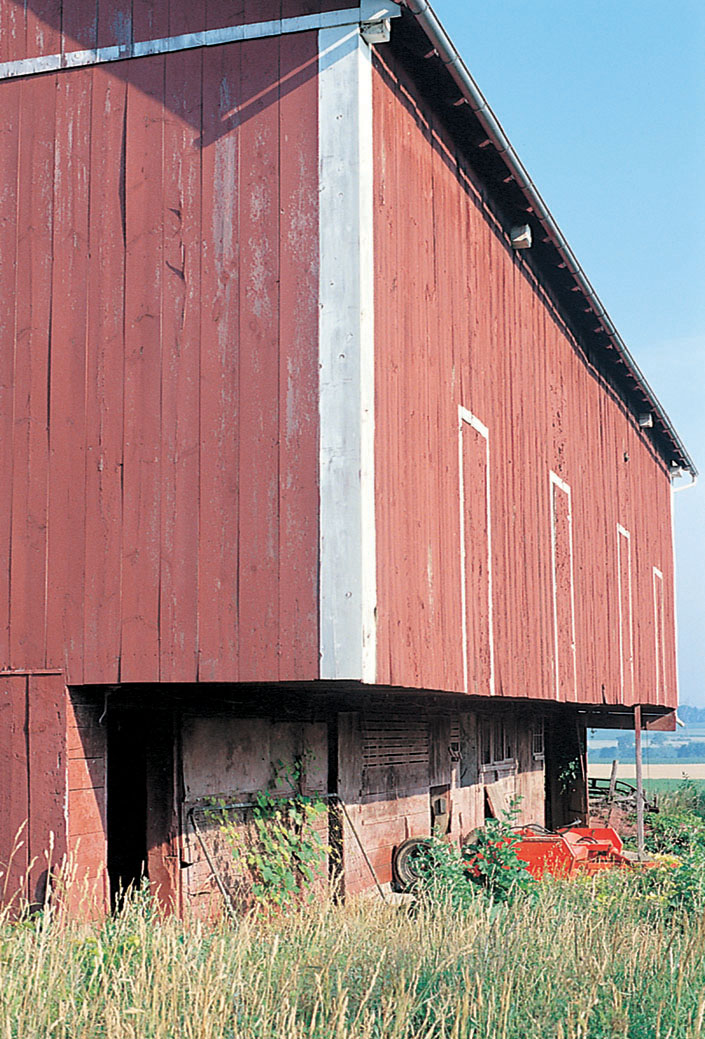

For example, the strongly Germanic Pennsylvanian folk culture region features an unusual Swiss-German type of barn, distinguished by an overhanging upper-level “forebay” on one side (Figure 2.3). In contrast, barns are usually attached to the rear of houses in the Yankee folk region. This region is also distinguished by an elaborate form of traditional gravestone art featuring “winged death heads.” This motif is most commonly found on graves dating from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. In their earliest forms these carvings depicted Death as a gruesome skull and bones in various formations. However, by the early nineteenth century, they were modified to resemble cherub faces with elaborate wings on either side.

Thinking Geographically

Question

How did the idea of this barn come from Switzerland to central Pennsylvania? Why would the extended-forebay design be useful to farmers who were fattening cattle?

33

The Upland South is noted in part for the abundance of a variety of distinctive house types built using notched-log construction. The African-American folk region displays such features as the “scraped-earth” cemetery, from which all grass is laboriously removed to expose the bare ground (Figure 2.4); the banjo, an instrument of African origin; and head kerchiefs worn by women. Stone grist mills with large sails to generate wind power for the grinding of grain help to characterize the Québec French folk region, as does the popularity of pétanque, a bowling game played with small metal balls. The Mormon folk culture region is identifiable by its farm villages clustered in checkerboard patterns and by the presence of distinctive derricks (lifting devices) used to loose-stack hay in agricultural fields. This gathering technique contrasts with baling methods more commonly used outside the Mormon folk culture region. The Western Plains ranch folk culture produced such material items as the beef wheel, a windlass (winch) used during butchering (Figure 2.5). These examples of material artifacts are only a few of the many that survive from various folk regions.

Thinking Geographically

Question

Would removing the vegetation in a cemetery have originally had a practical purpose? Why or why not?

Thinking Geographically

Question

How does this apparatus show the characteristic of folk culture of developing tools to meet an immediate need? Would this tool have been advertised? How do you know?

Folk Food Regions

Folk Food Regions

Perhaps no other aspect of folk culture endures as abundantly as traditional foods. In Latin America, for example, folk cultures remain vivid and vital in many regions, with diverse culinary traditions. Each displays distinctive choices of food and methods of preparation. For example, Mexican cuisine features abundant use of chile peppers and maize tortillas in cooking; the Caribbean areas offer combined rice-bean dishes and various rum drinks; in the Amazonian region, monkey and caiman are favored foods; Brazilian fare is distinguished by cuzcuz (cooked grain) and sugarcane brandy. These and other Latin American foods derive from American Indians, Africans, Spaniards, and Portuguese.

Is Popular Culture Placeless?

Is Popular Culture Placeless?

placelessness A spatial standardization that diminishes regional variety; may result from the spread of popular culture, which can diminish or destroy the uniqueness of place through cultural standardization on a local, national, or worldwide scale.

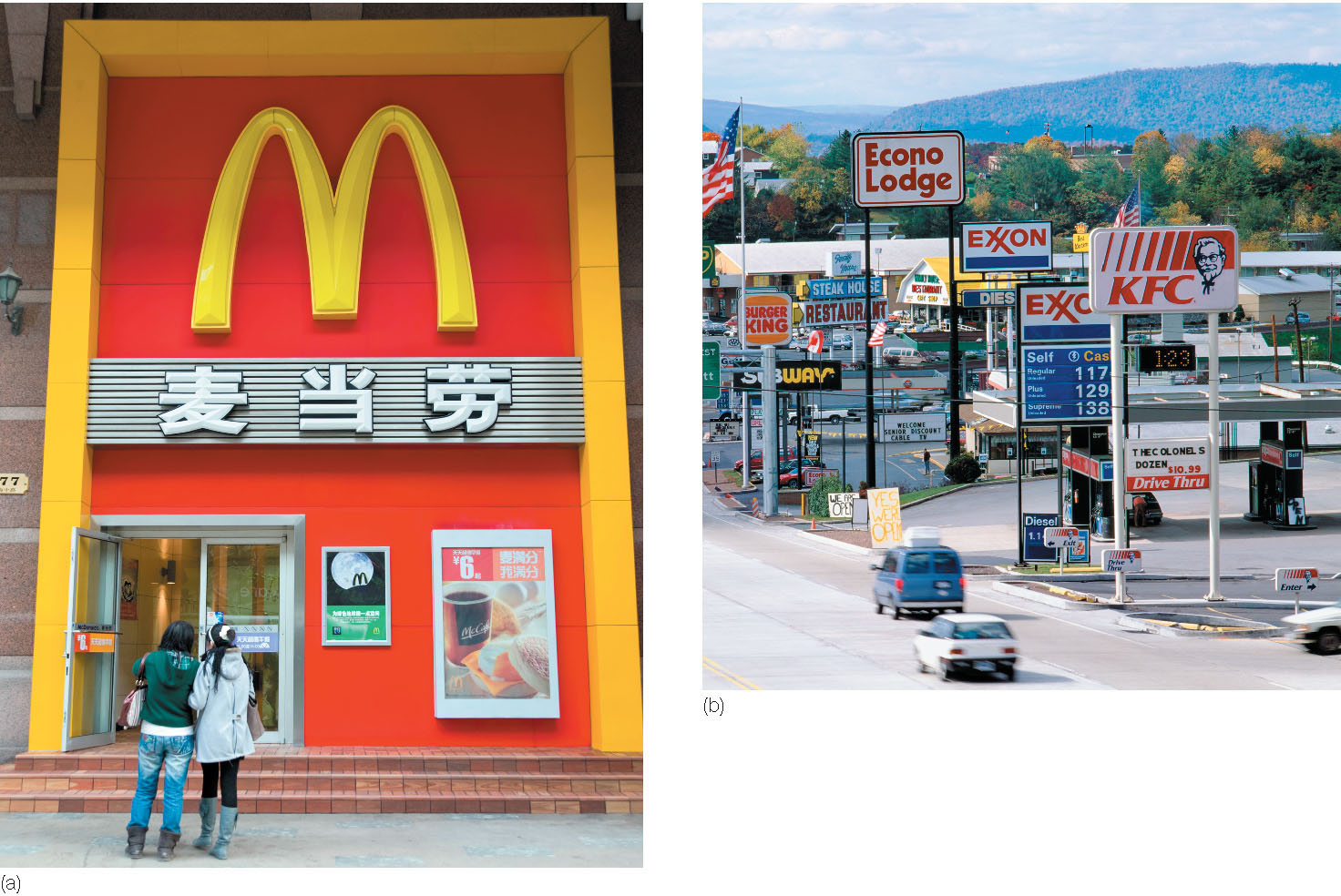

Superficially at least, popular culture varies less from place to place than does folk culture. In fact, Canadian geographer Edward Relph goes so far as to propose that popular culture produces a profound placelessness, a spatial standardization that diminishes regional variety and demeans the humanspirit. Others observe that one place seems pretty much like another, each robbed of its unique character by the pervasive influence of a continental or even worldwide popular culture (Figure 2.6). When compared with regions and places produced by folk culture, rich in their uniqueness (Figure 2.7), the geographical face of popular culture often seems expressionless. The greater mobility of people in popular culture weakens attachments to place and compounds the problem of placelessness. Moreover, the spread of McDonald’s, Starbucks, CNN, shopping malls, and much else further adds to the sense of placelessness.

Thinking Geographically

Question

Guess where these two photos were taken.

Thinking Geographically

Question

How can you tell that this is not a popular culture landscape?

34

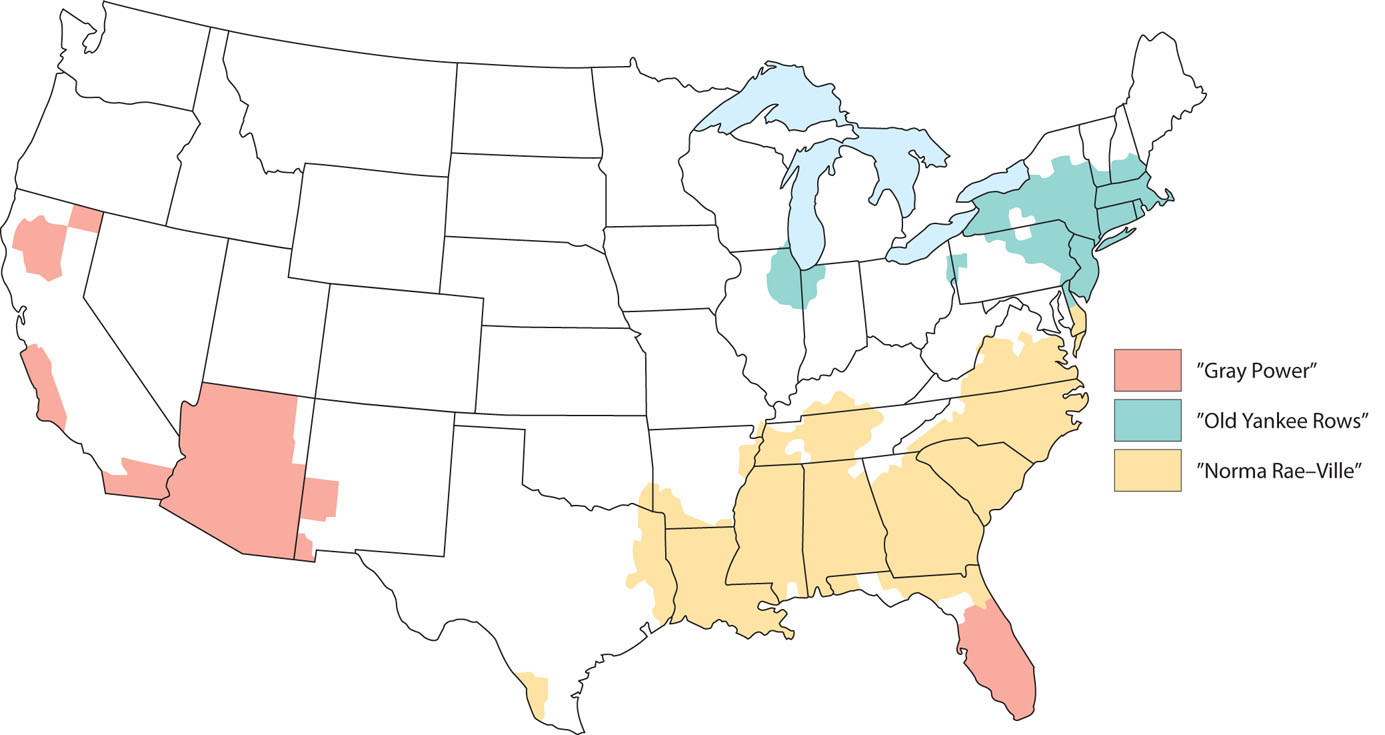

Is popular culture truly regionless and placeless? Many cultural geographers are cautious about making such a sweeping generalization. Geographer Michael Weiss, for example, argues in his book The Clustering of America that “American society has become increasingly fragmented” and identifies 40 “lifestyle clusters” based on postal zip codes. “Those five digits can indicate the kinds of magazines you read, the meals you serve at dinner,” and what political party you support. “Tell me someone’s zip code and I can predict what they eat, drink, drive—even think.” The lifestyle clusters, each of which is a formal culture region, bear Weiss’s colorful names—such as “Gray Power” (upper-middle-class retirement areas), “Old Yankee Rows” (older ethnic neighborhoods of the Northeast), and “Norma Rae–Ville” (lower- and middle-class southern mill towns, named for the Sally Field movie about the tribulations of a union organizer in a textile manufacturing town) (Figure 2.8). Old Yankee Rowers, for example, typically have a high school education, enjoy bowling and ice hockey, and are three times as likely as the average American to live in a row house or duplex. Residents of Norma Rae–Ville are mostly nonunion factory workers, have trouble earning a living, and consume twice as much canned stew as the national average. In short, a whole panoply of popular subcultures exist in America and the world at large, each possessing its own belief system, spokespeople, dress code, and lifestyle.

Thinking Geographically

Question

Are these regions accurately described? What would you change?

35

Reflecting on Geography

Question

Do you live in a “placeless” place in “nowhere USA”? If not, how is a distinctive regional form of popular culture reflected in your region?

Popular Food and Drink

Popular Food and Drink

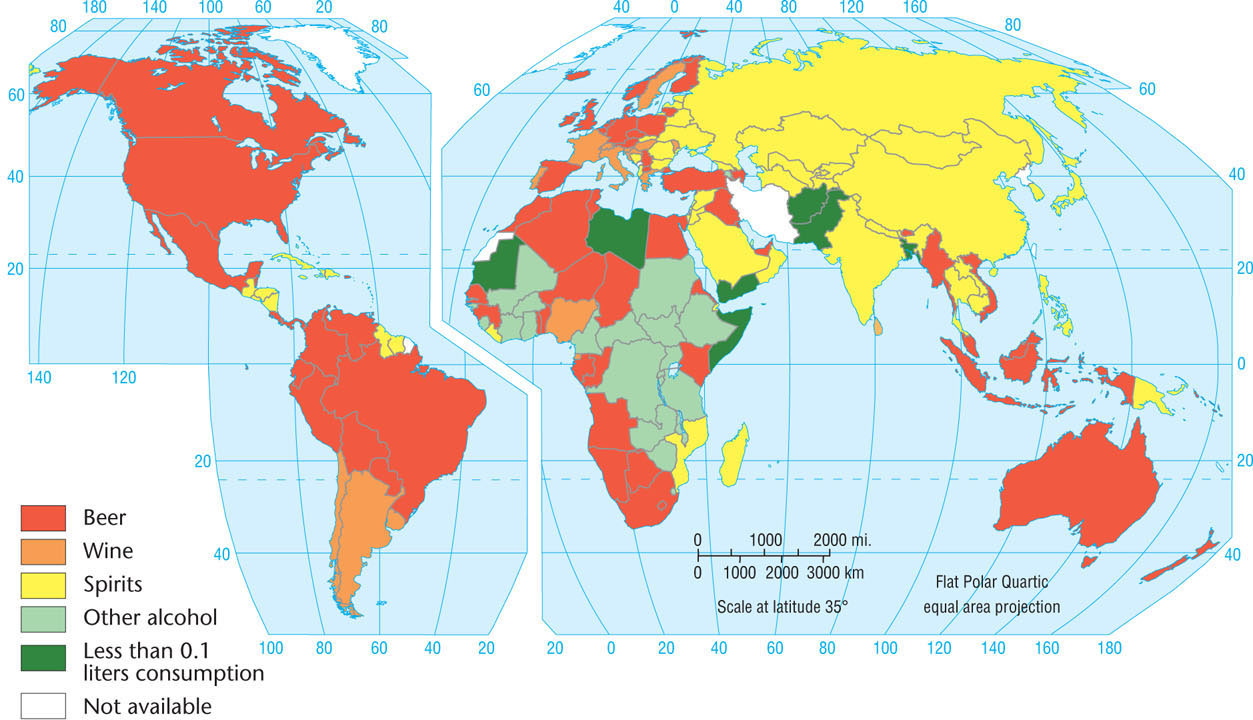

A persistent formal regionalization of popular culture is vividly revealed by what foods and beverages are consumed, which varies markedly from one part of a country to another and throughout different parts of the world. Figure 2.9 illustrates this variation in regard to alcoholic beverage preference. Differences in beverage choice can be attributed to differing cultural influences, including religious taboos regarding the consumption of alcohol. Patterns in beverage choice are also linked to patterns of economic development in many parts of the world. People in less developed regions may choose to consume “other” forms of alcohol (see map key) that can be made cheaply using local ingredients.

Thinking Geographically

Question

Why do you think that a preference for wine drinking is concentrated mainly in Western and Southern Europe and in the southern portion of South America?

Variations in beverage consumption are notable between regions in the United States as well. The highest per capita levels of U.S. beer consumption occur in the West, with the notable exception of Mormon Utah. Whiskey made from corn, manufactured both legally and illegally, has been a traditional southern alcoholic beverage, whereas wine is more common in California.

Foods consumed by members of the North American popular culture also vary from place to place. In the South, grits, barbecued pork and beef, fried chicken, and hamburgers are far more popular than elsewhere in the United States, whereas more pizza and submarine sandwiches are consumed in the North, the destination for many Italian immigrants. Contrasting food styles have developed as part of regionalized pop culture but can also often be traced to immigrant populations who, like the Italians in the Northeast, settled in these areas in times past. Figure 2.10 illustrates examples of foods that have become well known in various popular culture regions across the United States. One of these regional specialties, fried green tomatoes, became nationally famous following the release of a 1991 movie by the same name that depicts a cinematic view of Southern life.

Thinking Geographically

Question

Can you think of other popular regional foods that you have encountered in places you have lived or traveled?

36

The spread of global brands such as Coca-Cola and Kentucky Fried Chicken would seem to indicate increasing homogenization of food and beverage consumption. Yet many studies show that such brands have different meanings in different places around the world. Coca-Cola may represent modernization and progress in one place and foreign domination in another. Sometimes multinational corporations have to change their foods and beverages to suit local cultural preferences. For example, in Mumbai, India, McDonald’s has had to add local-style sauces to its menus. Rather than a simple one-way process of “Americanizing” Indian food preferences, local consumers are “Indianizing” McDonald’s.

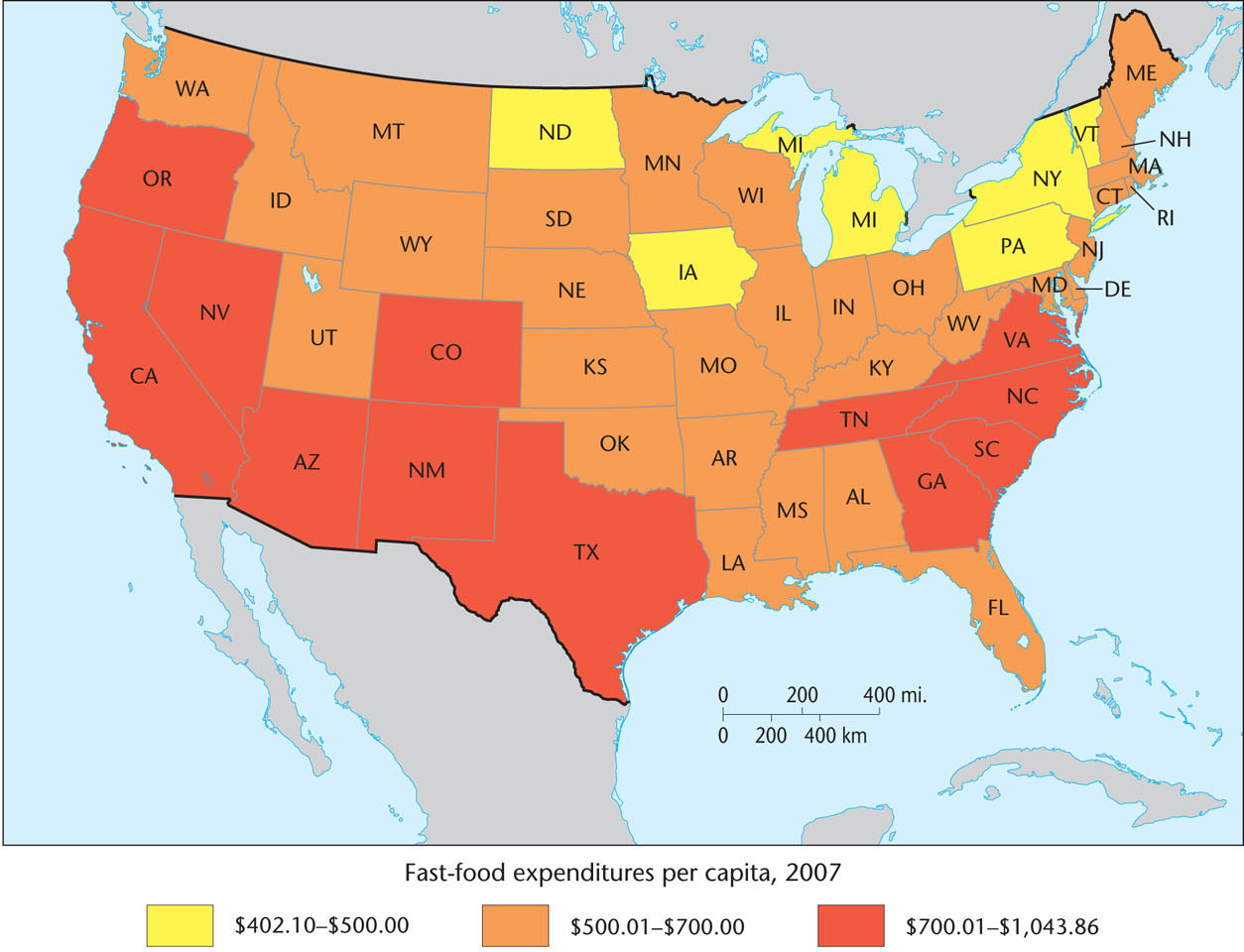

Fast food might seem to epitomize popular culture, yet its importance varies greatly even within the United States. Figure 2.11 shows that fast-food consumption dominates in the Southwest and West, while most of the country’s middle section partakes of (comparatively) less fast food. Such differences undermine the geographical uniformity or placelessness supposedly created by popular culture. Music provides another example.

Thinking Geographically

Question

What factors do you think might influence the fast-food consumption patterns revealed by this map?

Popular Music

Popular Music

Popular culture has spawned many styles of music, all of which reveal geographical patterns in levels of acceptance. Country music provides a good example of this phenomenon. Country music began to develop in the southern United States in the 1920s, incorporating aspects of several folk music traditions as well as cowboy music. Since that time, the popularity of country music has grown immensely, spreading to all 50 states and throughout the world. However, a distinct regional quality in the popularity of country music within the United States can still be observed. Geographer Ben Marsh illustrated this geographic pattern by creating a map based on state-name mentions in country music lyrics as a measure of the musical style’s popularity in those states (Figure 2.12, below).

Thinking Geographically

Question

How do you think a cartogram showing frequency of state-name mentions in rap/hip-hop lyrics might differ from the cartogram of state names in country music lyrics?

37

The cartogram suggests (by relative state size) that country music’s popularity is highest in and around its original southern source region. Tennessee, with its capital, Nashville, is the long-time heart of the country-music industry. The popularity of country music extends from this Tennessee core outward through the American South. Notice that the states in the northern tier of the country receive many fewer state-name mentions, indicating the corresponding lower level of country music’s popularity in that region.

Vernacular Culture Regions

Vernacular Culture Regions

A vernacular culture region is the product of the spatial perception of the population at large—a composite of the mental maps of the people. Such regions vary greatly in size, from small districts covering only part of a city or town to huge, multistate areas. Like most other geographical regions, they often overlap and usually have poorly defined borders.

vernacular culture region A culture region perceived to exist by its inhabitants; based in the collective spatial perception of the population at large; bearing a generally accepted name or nickname, such as Dixie.

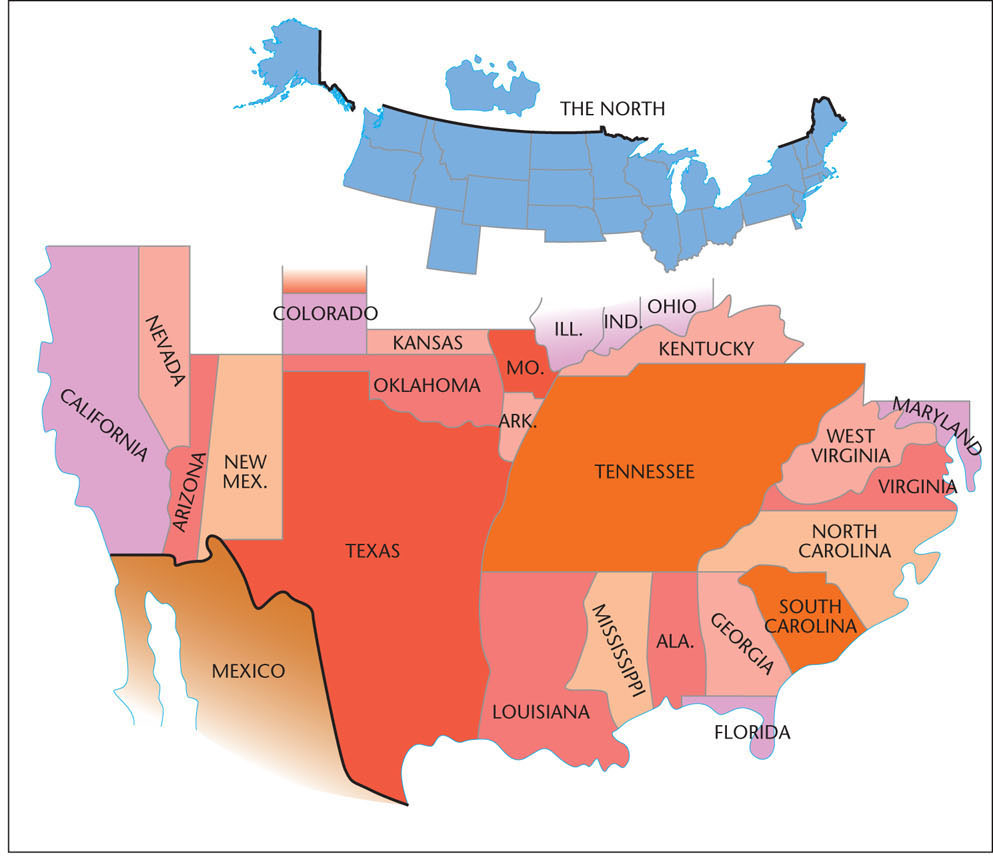

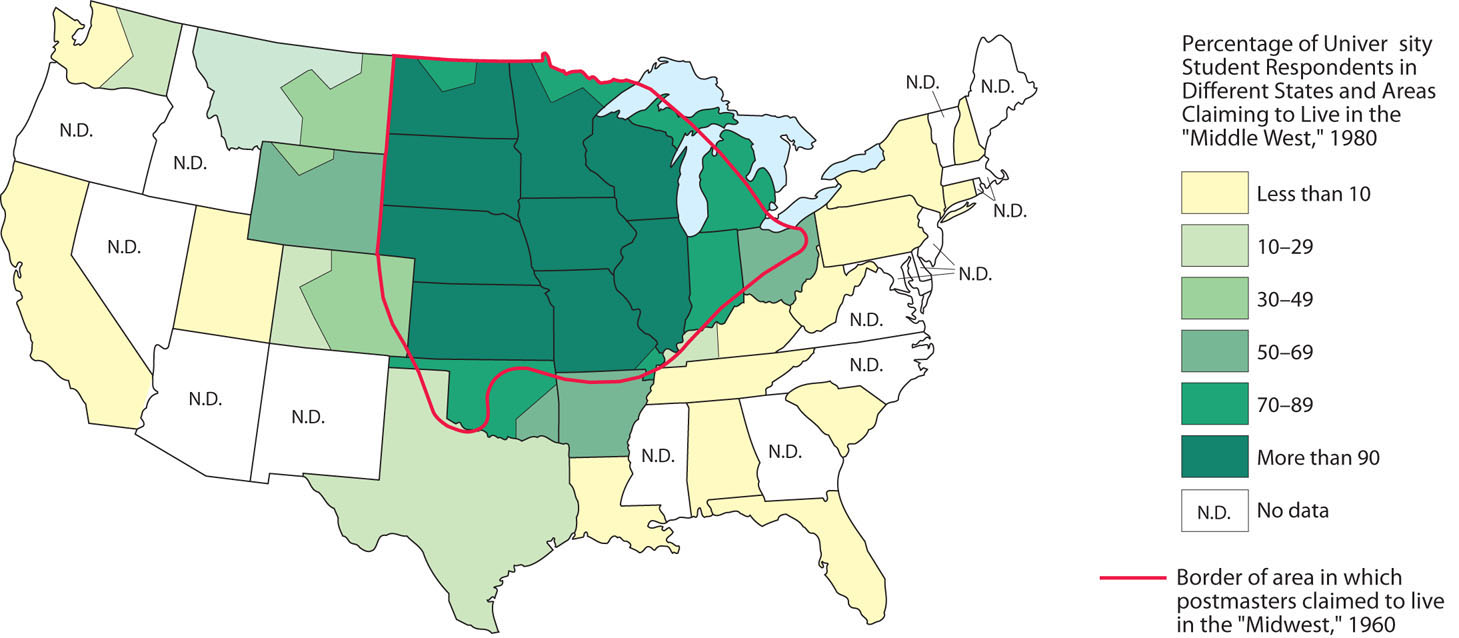

Almost every part of the industrialized Western world offers examples of vernacular regions based in the popular culture. Figure 2.13 shows some sizable vernacular regions in North America. Geographer Wilbur Zelinsky compiled these regions by determining the most common name for businesses appearing in the white pages of urban telephone directories. One curious feature of the map is the sizable populous district—in New York, Ontario, eastern Ohio, and western Pennsylvania—where no regional affiliation is perceived. Using a different source of information, geographer Joseph Brownell sought to delimit the popular “Midwest” in 1960 (Figure 2.14). He sent out questionnaires to postal employees in the midsection of the United States, from the Appalachians to the Rockies, asking each whether, in his or her opinion, the community lay in the “Midwest.” The results identified a vernacular region in which the residents considered themselves midwesterners. A similar survey done almost 30 years later, using student respondents, revealed a core-periphery pattern for the Midwest (see Figure #). As befits an element of popular culture, the vernacular region is often perpetuated by the mass media, especially radio and television.

Thinking Geographically

Question

Why are names containing “West” more widespread than those containing “East”? What might account for the areas where no region name is perceived?

Thinking Geographically

Question

Why would such a vernacular region remain fairly stable?

38

39

40