Linguistic Culture Regions

Linguistic Culture Regions

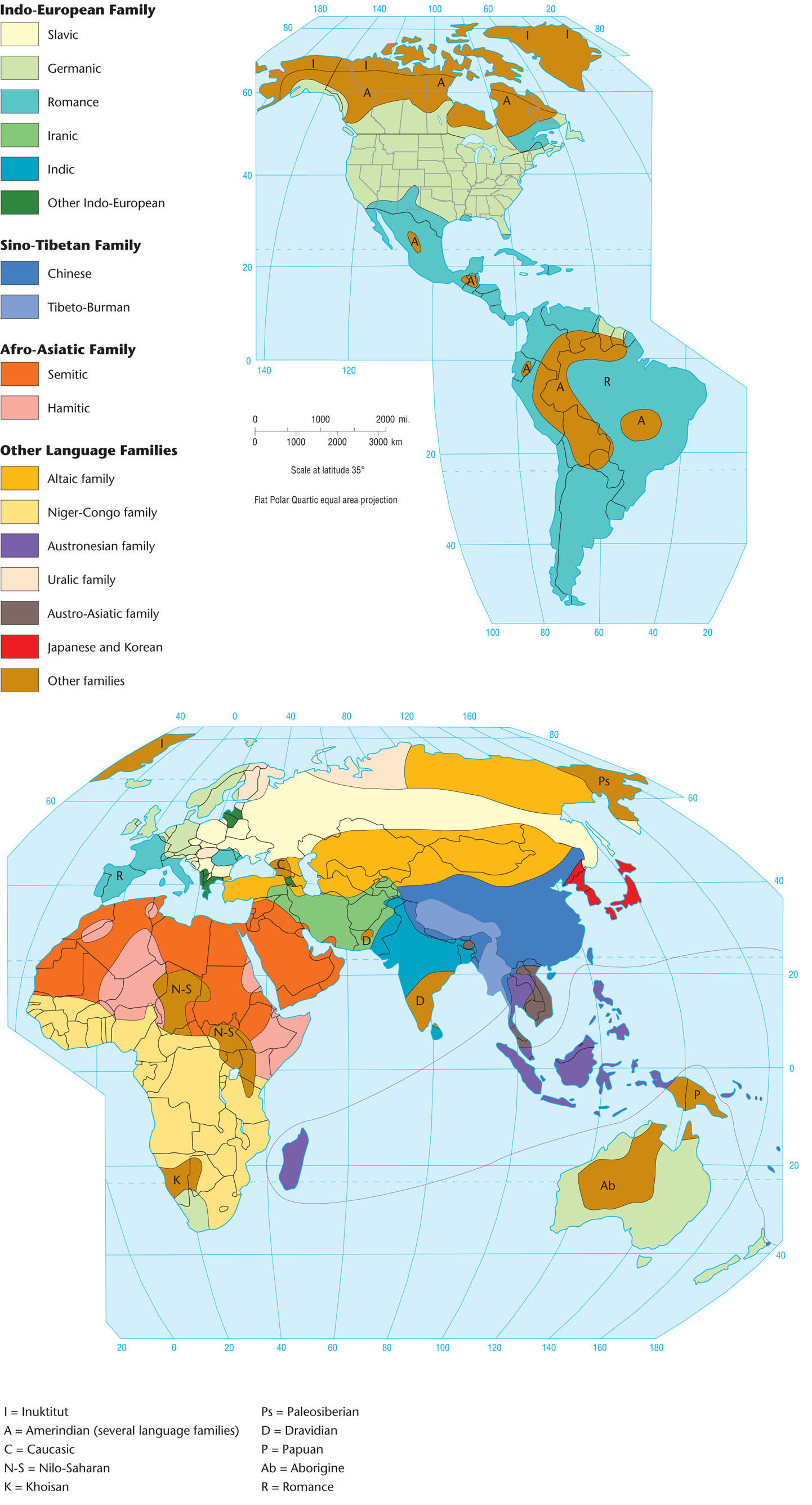

What is the geographical patterning of languages? Do various languages provide the basis for formal and functional culture regions? The spatial variation of speech is remarkably complicated, adding intricate patterns to the human mosaic (Figure 4.1). Because language is such a central component of culture, understanding the spatiality of language and how and why its patterns change over time provides a particularly valuable window into cultural geography. The logical place to begin our geographical study of language is with the regional theme.

Languages

Thinking Geographically

Question

In what types of areas do indigenous languages (shown in brown as “Other families” on the map) survive?

The Basics of Language

The Basics of Language

dialect A distinctive local or regional variant of a language that remains mutually intelligible to speakers of other dialects of that language.

Separate languages are those that cannot be mutually understood. In other words, a monolingual speaker of one language cannot comprehend the speaker of another. Dialects, by contrast, are mutually comprehensible variant forms of a language. A speaker of English, for example, can generally understand that language’s various dialects, whether the speaker comes from Australia, Scotland, or Mississippi. Nevertheless, a dialect is distinctive enough in vocabulary and pronunciation to label its speaker as hailing from one place or another or even from a particular city. About 6000 languages and many more dialects are spoken in the world today.

96

pidgin A composite language consisting of a small vocabulary borrowed from the linguistic groups involved in trade and commerce.

creole A language derived from a pidgin language that has acquired a fuller vocabulary and become the native language of its speakers.

When different linguistic groups come into contact, a pidgin language, characterized by a very small vocabulary derived from the languages of the groups in contact, often results. Pidgins primarily serve the purposes of trade and commerce: they facilitate exchange at a basic level but do not have complex vocabulary or grammatical structure. An example is Tok Pisin, meaning “talk business.” Tok Pisin is a largely English-derived pidgin spoken in Papua New Guinea, where it has become the official national language in a country where many native Papuan tongues are spoken. Although New Guinea pidgin is not readily intelligible to a speaker of Standard English, certain common words such as gut bai (“good-bye”), tenkyu (“thank you”), and haumas (“how much”) reflect the influence of English. When pidgin languages acquire fuller vocabularies and become native languages of their speakers, they are called creole languages. Obviously, deciding precisely when a pidgin becomes a creole language has at least as much to do with a group’s political and social recognition as it does with what are, in practice, fuzzy boundaries between language forms.

lingua franca A language of communication and commerce used widely where it is not a mother tongue.

bilingualism The ability to speak two languages fluently.

Another response to the need for speakers of different languages to communicate with each other is the elevation of one existing language to the status of a lingua franca. A lingua franca is a language of communication and commerce spoken across a wide area where it is not a mother tongue. Swahili enjoys lingua franca status in much of East Africa, where inhabitants speak a number of other regional languages and dialects. English is fast becoming a global lingua franca. Finally, regions that have linguistically mixed populations may be characterized by bilingualism, which is the ability to speak two languages with fluency. For example, along the U.S.–Mexican border, so many residents speak both English and Spanish (with varying degrees of fluidity) that bilingualism in practice—even if not in policy—means there is no need for a lingua franca.

97

Language Families

Language Families

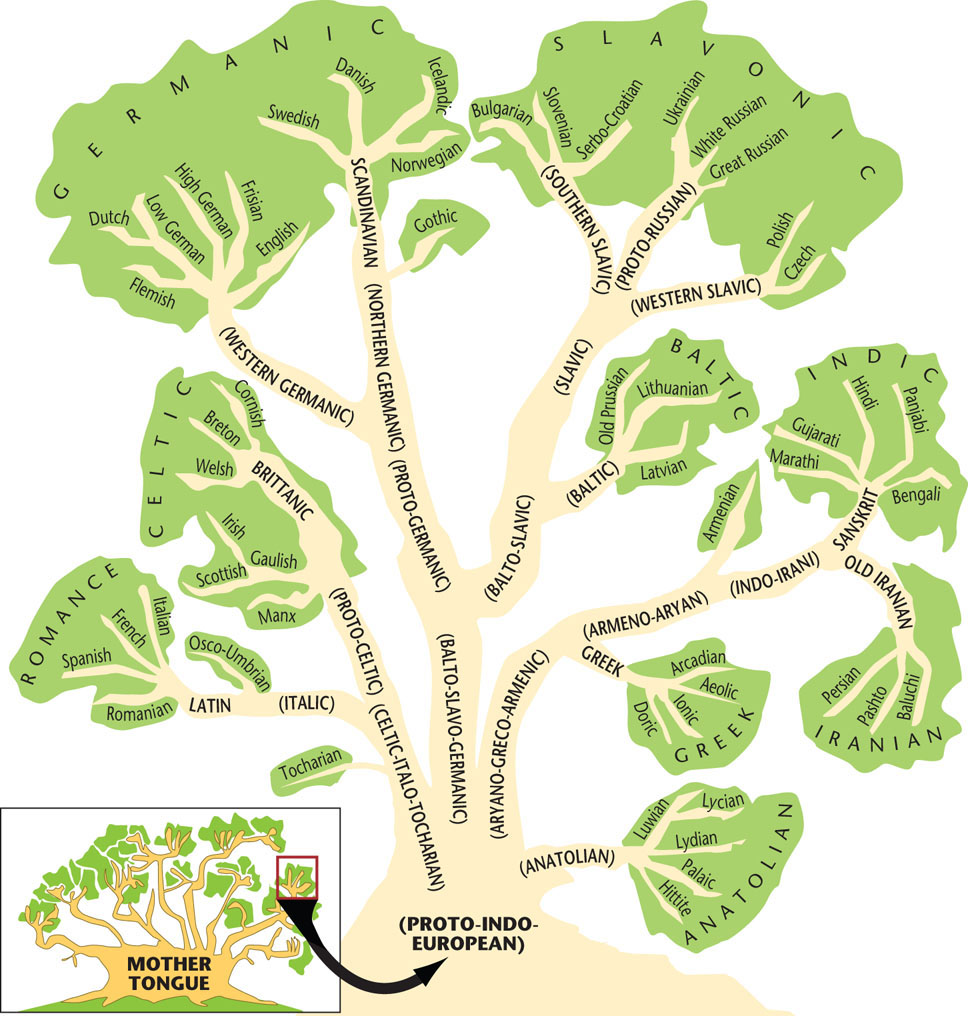

language family A group of related languages derived from a common ancestor.

One way in which geolinguists often simplify the mapping of languages is by grouping them into language families: tongues that are related and share a common ancestor. Words are simply arbitrary sounds associated with certain meanings. Thus, when words in different languages are alike in both sound and meaning, they may well be related. Over time, languages interact with one another, borrowing words, imposing themselves through conquest, or organically diverging from a common ground. Languages and their interrelations can thus be graphically depicted as a tree with various branches (Figure 4.2). This classification makes the complicated linguistic mosaic a bit easier to comprehend.

Thinking Geographically

Question

Why is a tree a useful metaphor for the relationship between languages? What are its weaknesses?

Indo-European Language Family

Indo-European Language Family The largest and most widespread language family is Indo-European, which is spoken on all of the continents and is dominant in Europe, Russia, North and South America, Australia, and parts of southwestern Asia and India (see Figure 4.1). Romance, Slavic, Germanic, Indic, Celtic, and Iranic are all Indo-European subfamilies. These subfamilies are in turn divided into individual languages. For example, English is a Germanic Indo-European language. Seven Indo-European tongues, including English, are among the 10 most spoken languages in the world as classified by numbers of native speakers (Table 4.1).

Table 4.1:

Languages Spoken at Home in the United States

| Language | Family | Speakers (in millions) | Main Areas Where Spoken |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese (all dialects) | Sino-Tibetan | 1,213 | China, Taiwan, Singapore |

| Spanish | Indo-European | 329 | Spain, Latin America, southwestern United States |

| English | Indo-European | 328 | British Isles, Anglo-America, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, Philippines, former British colonies in tropical Asia and Africa |

| Arabic (all dialects) | Afro-Asiatic | 221 | Middle East, North Africa |

| Hindi, Urdu | Indo-European | 182 | Northern India, Pakistan |

| Bengali | Indo-European | 181 | Bangladesh, eastern India |

| Portuguese | Indo-European | 178 | Portugal, Brazil, southern Africa |

| Russian | Indo-European | 144 | Russia, Kazakhstan, parts of Ukraine, other former Soviet republics |

| Japanese | Japanese and Korean | 122 | Japan |

| German (standard) | Indo-European | 90 | Germany, Austria, Switzerland, Luxembourg, eastern France, northern Italy |

| *Native speakers means the language is their mother tongue. | |||

| (Source: Lewis, M. Paul [ed.], 2009. Ethnologue: Languages of the World, 16th ed. Dallas, TX: SIL International. Online version: http://www.ethnologue.com.) | |||

Comparing the vocabularies of various Indo-European tongues reveals their kinship. For example, the English word mother is similar to the Polish matka, the Greek meter, the Spanish madre, the Farsi madar in Iran, and the Sinhalese mava in Sri Lanka. Such similarities demonstrate that these languages have a common ancestral tongue.

Sino-Tibetan Family

Sino-Tibetan Family Sino-Tibetan is another of the major language families of the world and is second only to Indo-European in numbers of native speakers. The Sino-Tibetan region extends throughout most of China and Southeast Asia (see Figure 4.1). The two language branches that make up this group, Sino- and Tibeto-Burman, are believed to have a common origin some 6000 years ago in the Himalayan Plateau; speakers of the two language groups subsequently moved along the great Asian rivers that originate in this area. Sino refers to China and in this context indicates the various languages spoken by more than 1.2 billion people in China. Han Chinese (Mandarin) is spoken in a variety of dialects and serves as the official language of China. The nearly 400 languages and dialects that make up the Burmese and Tibetan branch of this language family border the Chinese language region on the south and west. Other East Asian languages, such as Vietnamese, have been heavily influenced by contact with the Chinese and their languages, although it is not clear that they are linguistically related to Chinese at all.

98

Afro-Asiatic Family

Afro-Asiatic Family The third major language family is the Afro-Asiatic. It consists of two major divisions: Semitic and Hamitic. The Semitic languages cover the area from the Arabian Peninsula and the Tigris-Euphrates river valley of Iraq westward through Syria and North Africa to the Atlantic Ocean. Despite the considerable size of this region, there are fewer speakers of the Semitic languages than you might expect because most of the areas that Semites inhabit are sparsely populated deserts. Arabic is by far the most widespread Semitic language and has the greatest number of native speakers, about 221 million. Although many different dialects of Arabic are spoken, there is only one written form.

polyglot A mixture of languages.

Hebrew, which is closely related to Arabic, is another Semitic tongue. For many centuries, Hebrew was a “dead” language, used only in religious ceremonies by millions of Jews throughout the world. With the creation of the state of Israel in 1948, a common language was needed to unite the immigrant Jews, who spoke the languages of their many different countries of origin. Hebrew was revived as the official national language of what otherwise would have been a polyglot, or multilanguage, state (Figure 4.3). Amharic, a third major Semitic tongue, today claims 18 million speakers in the mountains of East Africa.

Thinking Geographically

Question

What examples of signs in more than one language can you find in your community?

Smaller numbers of people who speak Hamitic languages share North and East Africa with the speakers of Semitic languages. Like the Semitic languages, these tongues originated in Asia but today are spoken almost exclusively in Africa by the Berbers of Morocco and Algeria, the Tuaregs of the Sahara, and the Cushites of East Africa.

Other Major Language Families

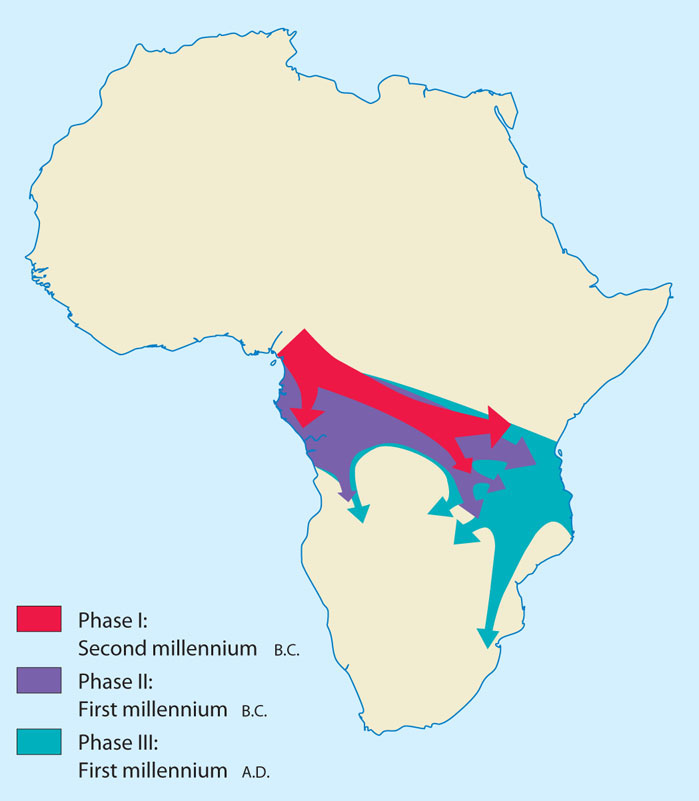

Other Major Language Families Most of the rest of the world’s population speak languages belonging to one of six remaining major families. The Niger-Congo language family, also called Niger-Kordofanian, dominates Africa south of the Sahara Desert. The greater part of the Niger-Congo culture region belongs to the Bantu subgroup. Both Niger-Congo and its Bantu constituent are fragmented into a great many different languages and dialects, including Swahili. The Bantu and their many related languages spread from what is now southeastern Nigeria about 4000 years ago, first west and then south in response to climate change and new agricultural techniques (Figure 4.4).

Thinking Geographically

Question

Compare this map with Figure 4.7. How far did the resulting Niger-Congo family extend? What language seems to have survived in a restricted region?

Flanking the Slavic Indo-Europeans on the north and south in Asia are the speakers of the Altaic language family, including Turkic, Mongolic, and several other subgroups. The Altaic homeland lies largely in the inhospitable deserts, tundra, and coniferous forests of northern and central Asia. Also occupying tundra and grassland areas adjacent to the Slavs is the Uralic family. Finnish and Hungarian are the two most widely spoken Uralic tongues, and both enjoy the status of official languages in their respective countries.

One of the most remarkable language families in terms of distribution is the Austronesian. Representatives of this group live mainly on tropical islands stretching from Madagascar, off the east coast of Africa, through Indonesia and the Pacific islands to Hawaii and Easter Island. This longitudinal span is more than half the distance around the world. The north-south, or latitudinal, range of this language area is bounded by Hawaii and Taiwan in the north and New Zealand in the south. The largest single language in this family is Malay-Indonesian, with 58 million native speakers, but the most widespread is Polynesian.

Japanese and Korean, with about 200 million speakers combined, probably form another Asian language family. The two perhaps have some link to the Altaic family, but even their kinship to each other remains controversial and unproven.

In Southeast Asia, the Vietnamese, Cambodians, Thais, and some tribal peoples of Malaysia and parts of India speak languages that constitute the Austro-Asiatic family. They occupy an area into which Sino-Tibetan, Indo-European, and Austronesian languages have all encroached.

Language’s Shifting Boundaries

Language’s Shifting Boundaries

Dialects, as well as the language families discussed previously, reveal a vivid geography. Their boundaries—what separates them from other dialects and languages—shift over time, both spatially and in terms of what elements they contain or discard.

99

isogloss The border of usage of an individual word or pronunciation.

Geolinguists map dialects by using isoglosses, which indicate the spatial borders of individual words or pronunciations. The dialect boundaries between Latin American Spanish speakers using tú and those using vos are clearly defined in some areas, as shown on the map in Figure 4.5. The choice of tú or vos for the second-person singular carries with it a cultural indication. Vos represents a usage closer to the original Spanish but is considered by many in the Spanish-speaking world to be rather archaic and, in fact, has died out in Spain itself. In other regions, particularly throughout Argentina, vos has long been used by the media; often, it is considered to reflect the “standard” dialect and usage for the area in which it is used. Because certain words or dialects can fall out of fashion or simply become overwhelmed by an influx of new speakers, isogloss boundaries are rarely clear or stable over time. Indeed, in Central America, the media are increasingly using vos—long used in conversation in the region—thus ele vating vos to a more official status covering a larger territory. Because of this, geolinguists often disagree about how many dialects are present in an area or exactly where isogloss borders should be drawn. The language map of any place is a constantly shifting kaleidoscope.

Thinking Geographically

Question

Why do you think standard Spanish textbooks in the United States teach tú as the second-person singular form?

The dialects of American English provide another good example. By the time of the American Revolution at least three major dialects, corresponding to major culture regions, had developed in the eastern United States: the Northern, Midland, and Southern dialects (Figure 4.6). As the three subcultures expanded westward, their dialects spread and fragmented. Nevertheless, they retained much of their basic character, even beyond the Mississippi River. These culture regions have unusually stable boundaries. Even today, the “r-less” pronunciation of words such as car (“cah”) and storm (“stohm”), characteristic of the East Coast Midland regions, is readily discernible in the speech of its inhabitants.

Thinking Geographically

Question

What might have caused the Hoosier Apex and the Missouri Apex of Hill Southern speech to penetrate Indiana and Missouri, respectively?

100

Although we are sometimes led to believe that Americans are becoming more alike as a national culture overwhelms regional ones, the current status of American English dialects suggests otherwise. Linguistic divergence is still under way, and dialects continue to mutate on a regional level, just as they always have. Local variations in grammar and pronunciation proliferate, confounding the proponents of standardized speech and defying the homogenizing influence of the Internet, television, and other mass media.

Shifting language boundaries involve content, as well as spatial reach, and this too changes over time. Today, for example, some of the unique vocabulary of American English dialects is becoming old-fashioned. For instance, the term icebox, which was literally a wooden box with a compartment for ice that was used to cool food, was used widely throughout the United States to refer to the precursor of the refrigerator. Although the modern electric refrigerator is ubiquitous in the United States today, some people, particularly those of older generations and in the South, still use the term icebox. Many young people, by contrast, no longer say the entire word refrigerator, shortening it instead to fridge.

slang Words and phrases that are not part of a standard, recognized vocabulary for a given language but that are nonetheless used and understood by some of its speakers.

As illustrated by the birth of the new word fridge, slang terms are quite common in most languages, and American English is no exception. Slang refers to words and phrases that are not a part of a standard, recognized vocabulary for a given language but are nonetheless used and understood by some or most of its speakers.

Often, subcultures (for example, youth, street gangs, and users of certain Internet social networking or gaming sites), have their own slang that is used within that community but is not readily understood by nonmembers.

Slang words tend to be used for a period and then are discarded as newer terms replace them. For example, in the 1980s in the United States, awesome and rad(ical) were used to refer to things that were desirable or fantastic. These slang terms were popularized largely as a result of movies and other media that idealized the California culture of groups such as surfers and “Valley girls” and diffused it nationwide. Although many people today still recognize these words, the current generation of young people is adopting new slang terms emerging from hip-hop culture and other subgroups within the American population. Their children, in turn, will likely use yet another set of slang words to express themselves in the future.

101

In the United States today, many descendants of Spanish speakers have adapted their speech to include words and variants of words in both Spanish and English in a dialect known as Spanglish. Similarly, French and English have been blended together by certain cultural groups within the United States, Canada, and former French colonies like Cameroon to produce Franglais, or Franglish. This combination has been particularly notable among native English speakers and immigrant bilingual language learners in French-speaking regions of Canada like the province of Québec. The provincial government of Québec has officially discouraged such “incorrect” uses of the French language, but the new language blend appears to be persisting despite these admonishments.