Linguistic Landscapes

Linguistic Landscapes

In what ways are languages visible and, as a result, part of the cultural landscape? Road signs, billboards, graffiti, placards, and other publicly displayed writings not only reveal the locally dominant language but also can be a visual index to bilingualism, linguistic oppression of minorities, and other facets of linguistic geography (Figure 4.16). Furthermore, differences in writing systems render some linguistic landscapes illegible to those not familiar with these forms of writing (Figure 4.17 below).

Thinking Geographically

Question

What part of this sign is international and understandable to speakers of any language? Why would it have been included?

Thinking Geographically

Question

How does the use of a script like this create unity within the area that uses it? How does it create barriers to diffusion between its region and the rest of the world?

Messages

Messages

Linguistic landscapes send messages, both friendly and hostile. Often these messages have a political content and deal with power, domination, subjugation, or freedom. In Turkey, for example, until recently Kurdish-speaking minorities were not allowed to broadcast music or television programs in Kurdish, to publish books in Kurdish, or even to give their children Kurdish names. Because Turkey wishes to join the European Union, these minority language restrictions have come under intense outside scrutiny. In 2002, Turkey reformed its legal restrictions to allow the Kurdish language to be used in daily life but not in public education. The Canadian province of Québec, similarly, has tried to eliminate English-language signs. French-speaking immigrants settled Québec, and its official language is French, in contrast to Canada’s policy of bilingualism in English and French. By 2003, in most regions of Ireland, formerly English-only place name signs have been modified to reflect the country’s dual official languages of Irish (Gaeilge) and English. Irish place names are listed first, with the more recent English place names listed second. In specially designated Irish culture preservation regions of the country (known as Gaeltachts), only Gaeilge appears on place name signs, while English has no legal status at all. The suppression of minority languages and moves to reinstate them in the landscape offer an indication of the social and political status of minority populations more generally.

112

Other types of writing, such as gang-related graffiti, can denote ownership of territory or send messages to others that they are not welcome (Figure 4.18). Only those who understand the specific gang symbols used will be able to decipher the message. Misreading such writing can have dangerous consequences for those who stray into unfriendly territory. In this way, gang symbols can be understood as a dialect that is particular to a subculture and transmitted through symbols or a highly stylized script.

Thinking Geographically

Question

How is gang use of stylized script in their graffiti similar to the effect of languages written in unique kinds of script?

Toponyms

Toponyms

toponym A place name, usually consisting of two parts, the generic and the specific.

Language and culture also intersect in the names that people place on the land, whether they are given to settlements, terrain features, streams, or various other aspects of their surroundings. These place names, or toponyms, often directly reflect the spatial patterns of language, dialect, and ethnicity. Toponyms become part of the cultural landscape when they appear on signs and placards. Toponyms can be very revealing, because, as geographer Stephen Jett said, they often provide insights into “linguistic origins, diffusion, habitat, and environmental perception.” Many place names consist of two parts—the generic and the specific. For example, in the American place names Huntsville, Harrisburg, Ohio River, Newfound Gap, and Cape Hatteras, the specific segments are Hunts-, Harris-, Ohio, Newfound, and Hatteras. The generic parts, which tell what kind of place is being described, are -ville, -burg, River, Gap, and Cape.

113

Types of Toponyms

descriptive toponym A place name that describes a physical feature or environmental characteristic of a place.

commemorative toponym A place name that honors a famous or important person.

manufactured toponym A place name that is made up, often by early founders of a settlement or an influential member of a community.

Types of Toponyms Geographers classify toponyms into several types when studying their origins and the cultures that conceived them. Table 4.4 provides examples of some common types of toponyms found on the cultural landscape. One type is a descriptive toponym, which describes some physical feature or environmental characteristic of a place—for example, the Rocky Mountains. Sometimes, rather than being named for a physical feature, places are named to honor a famous person. An example of this type of commemorative toponym is the Hudson River, which was named for explorer Henry Hudson. Another type of place name is a manufactured toponym, or one that has simply been made up. An example of this form of place naming occurred in Truth or Consequences, Arizona, in the 1950s, when a popular radio program by the same name challenged towns to rename themselves after the program. The first that did so won the right to have the radio show broadcast live from their town. In this way, a town once called Hot Springs became known as Truth or Consequences and has remained so ever since.

Table 4.4:

Types of Toponyms

| Type of Toponym | Origin | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Commemorative | Honors a famous or important person |

|

| Commendatory | Praises some physical or environmental characteristic |

|

| Descriptive | Describes a physical feature or environmental characteristic |

|

| Incident related | Recalls an historic event |

|

| Manufactured | Made-up or coined |

|

| Mistaken | Traceable to an historic error in identification or translation |

|

| Possessive | Indicates an historic claim to ownership or control of a place |

|

| Shift | Relocated from another place, often settlers’ homeland |

|

114

Generic Toponyms of the United States

Generic Toponyms of the United States

generic toponym The descriptive part of many place names, often repeated throughout a cultural area.

Generic toponyms are of greater potential value to the cultural geographer than specific names because they appear again and again throughout a culture region. There are literally thousands of generic place names, and every culture or subculture has its own distinctive set of them. They are particularly valuable both in tracing the spread of a culture and in reconstructing culture regions of the past. Sometimes generic toponyms provide information about changes people wrought long ago in their physical surroundings.

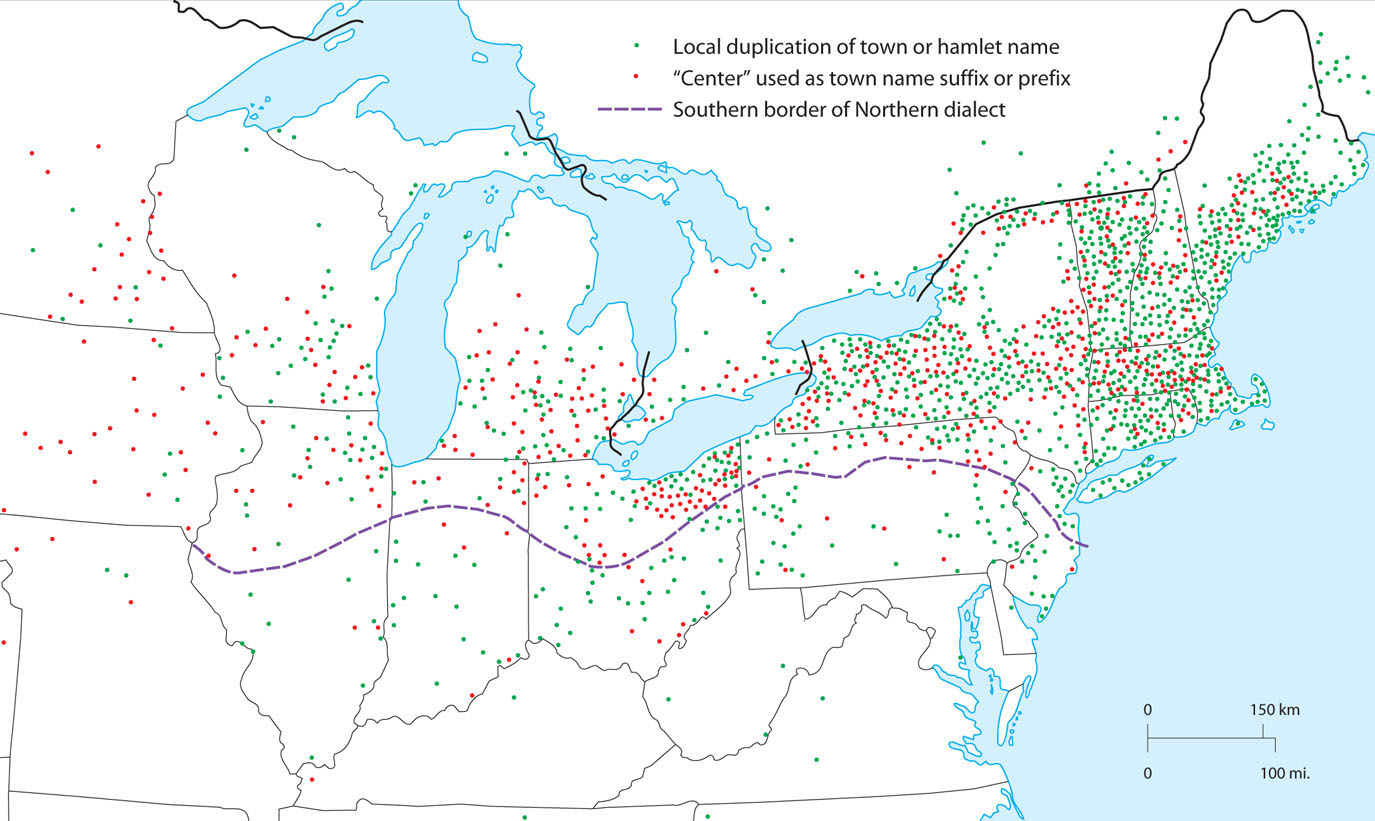

The three dialects of the eastern United States (see Figure 4.6)—Northern, Midland, and Southern—illustrate the value of generic toponyms in cultural geographical detective work. For example, New Englanders, speakers of the Northern dialect, often used the terms Center and Corners in the names of the towns or hamlets. Outlying settlements frequently bear the prefix East, West, North, or South, with the specific name of the township as the suffix. Thus, in Randolph Township, Orange County, Vermont, we find settlements named Randolph Center, South Randolph, East Randolph, and North Randolph. A few miles away lies Hewetts Corners.

These generic usages and duplications are peculiar to New England, and we can locate areas settled by New Englanders as they migrated westward by looking for such place names in other parts of the country. A trail of “Centers” and name duplications extending westward from New England through upstate New York and Ontario and into the upper Midwest clearly indicates their path of migration and settlement (Figure 4.19). Toponymic evidence of New England exists in areas as far afield as Walworth County, Wisconsin, where Troy, Troy Center, East Troy, and Abels Corners are clustered; in Dufferin County, Ontario, where one finds places such as Mono Centre; and even in distant Alberta, near Edmonton, where the toponym Michigan Centre doubly suggests a particular cultural diffusion. Similarly, we can identify Midland American areas by such terms as Gap, Cove, Hollow, Knob (a low, rounded hill), and -burg, as in Stone Gap, Cades Cove, Stillhouse Hollow, Bald Knob, and Fredericksburg. We can recognize southern speech by such names as Bayou, Gully, and Store (for rural hamlets), as in Cypress Bayou, Gum Gully, and Halls Store.

Thinking Geographically

Question

Based on this trait, where was initial settlement by Yankees most common? What other landscape features might you find in those places?

115

Toponyms and Cultures of the Past

Toponyms and Cultures of the Past

Place names often survive long after the culture that produced them vanishes from an area, thereby preserving traces of the past. Australia abounds in Aborigine toponyms, even in areas from which the native peoples disappeared long ago (Figure 4.20). No toponyms are more permanently established than those identifying physical geographical features, such as rivers and mountains. Even the most absolute conquest, exterminating an aboriginal people, usually does not entirely destroy such names. Quite the contrary, in fact. Geographer R. D. K. Herman speaks of anticonquest, in which the defeated people finds its toponyms venerated and perpetuated by the conqueror, who at the same time denies the people any real power or cultural influence. The abundance of Native American toponyms in the United States provides an example. India, however, has recently decided to revert to traditional toponyms; many Indian place names had been Anglicized under British colonial rule (Figure 4.21).

Thinking Geographically

Question

What similar kinds of toponyms can you name in your region?

Thinking Geographically

Question

What other countries or cities changed their names after independence?

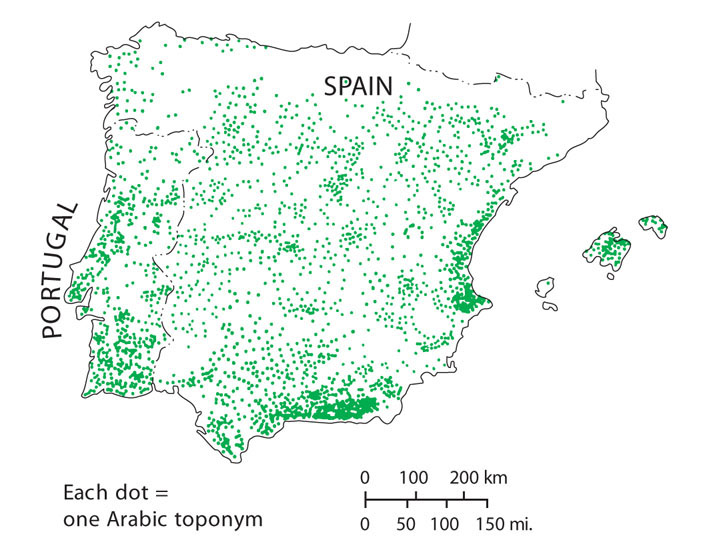

In Spain and Portugal, seven centuries of Moorish rule left behind a great many Arabic place names (Figure 4.22). An example is the prefix guada- on river names (as in Guadalquivir and Guadalupejo). The prefix is a corruption of the Arabic wadi, meaning “river” or “stream.” Thus, Guadalquivir, corrupted from Wadi-al-Kabir, means “the great river.” The frequent occurrence of Arabic names in any particular region or province of Spain reveals the remnants of Moorish cultural influence in that area. Many such names were brought to the Americas through Iberian conquest, so that Guadalajara, for example, appears on the map as an important Mexican city.

Thinking Geographically

Question

In what parts of Iberia did Moorish rule probably last longest? In what parts were the Moors particularly powerful?

New Zealand, too, offers some intriguing examples of the subtle messages that can be conveyed by archaic toponyms. The native Polynesian people of New Zealand are the Maori. As cultural geographer Hong-key Yoon has observed, the survival rate of Maori names for towns varies according to the size of its population. The smaller the town, the more likely it is to bear a Maori name. The four largest New Zealand cities all have European names, but of the 20 regional centers, with populations of 10,000 to 100,000, 40 percent have Maori names. Almost 60 percent of the towns with fewer than 10,000 inhabitants bear Maori toponyms. Similarly, whereas only 20 percent of New Zealand’s provinces have Maori names, 56 percent of the counties do. Nearly all streams, hills, and mountains retain Maori names. The implication is that the British settlement of New Zealand was largely an urban phenomenon.

116