Religious Culture Regions

Religious Culture Regions

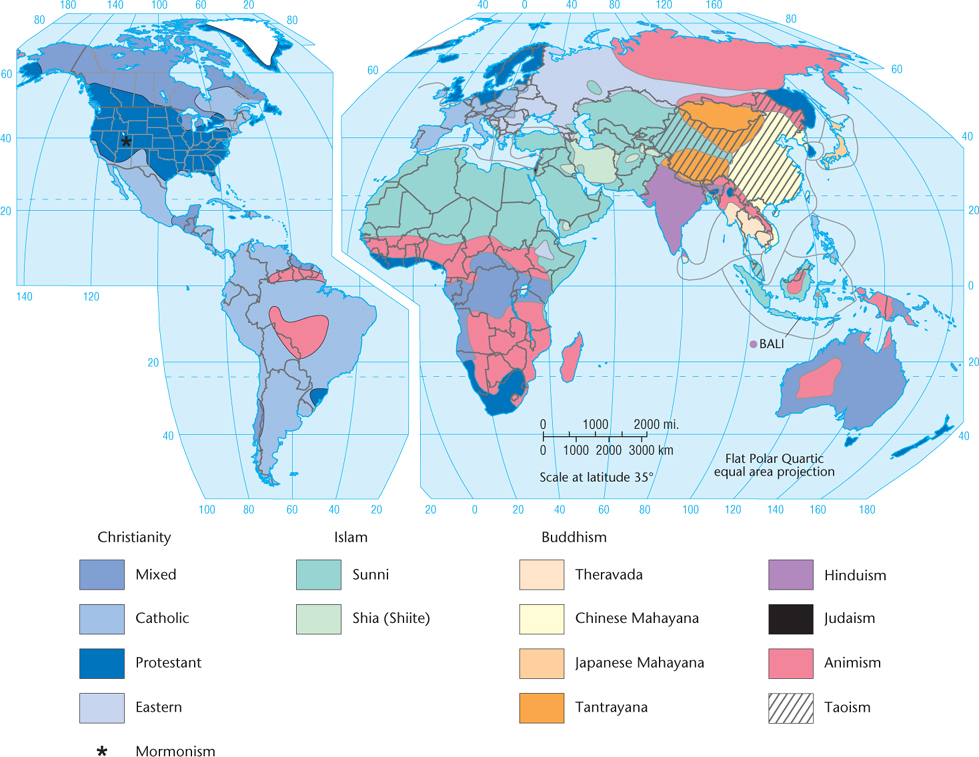

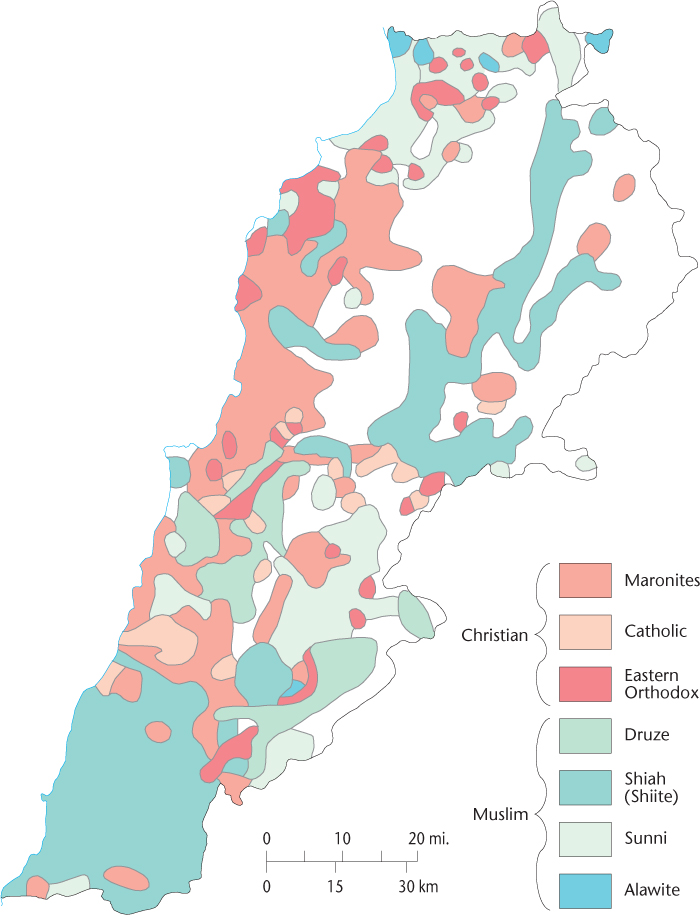

What is the spatial patterning of religious faiths? Because religion, like all of culture, has a strong territorial tie, religious culture regions abound. The most basic kind of formal religious culture region depicts the spatial distribution of organized religions (Figure 7.2). Some parts of the world exhibit an exceedingly complicated pattern of religious adherence, and the boundaries of formal religious culture regions, like most cultural borders, are rarely sharp (Figure 7.3). Persons of different faiths often live in the same province or town.

182

Major Religions

Thinking Geographically

Question 7.2

What kinds of areas are dominantly animist? How does this relate to patterns of language and the distribution of indigenous peoples?

179

Thinking Geographically

Question 7.3

What is the impact of the concentration of Muslims in the southern part of Lebanon, along the border with Israel?

Judaism

Judaism

Judaism is a 4000-year-old religion and the first major monotheistic faith to arise in southwestern Asia. It is the parent religion of Christianity and is also closely related to Islam. Jews believe in one God who created humankind for the purpose of bestowing kindness on them. As with Islam and Christianity, people are rewarded for their faith, are punished for violating God’s commandments, and can atone for their sins. The Jewish holy book, or Torah, comprises the first five books of the Hebrew Bible. In contrast to the other monotheistic faiths, Judaism is not proselytic and has remained an ethnic religion through most of its existence.

Judaism has split into a variety of subgroups, partly as a result of the Diaspora, a term that refers to the forced dispersal of the Jews from Palestine in Roman times and the subsequent loss of contact among the various colonies. Jews, scattered to many parts of the Roman Empire, became a minority group wherever they went. In later times, they spread throughout much of Europe, North Africa, and Arabia. Those Jews who lived in Germany and France before migrating to central and eastern Europe are known as the Ashkenazim; those who never left the Middle East and North Africa are called Mizrachim; and those from Spain and Portugal are known as Sephardim. Spain expelled its Sephardic Jews in 1492, the same year that Christopher Columbus set sail for the New World. It was not until the quincentennial of both events, in 1992, that the Spanish government issued an official apology for the expulsion.

The late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries witnessed large-scale Ashkenazic migration from Europe to America. The Holocaust that befell European Judaism during the Nazi years involved the systematic murder of perhaps a third of the world’s Jewish population, mainly Ashkenazim. Europe ceased to be the primary homeland of Judaism, and many of the survivors fled overseas, mainly to the Americas and later to the newly created state of Israel. Today, Judaism has about 13 million adherents throughout the world. At present, roughly 6.5 million, or about half, live in North America, and slightly more than 5 million live in Israel.

Christianity

Christianity

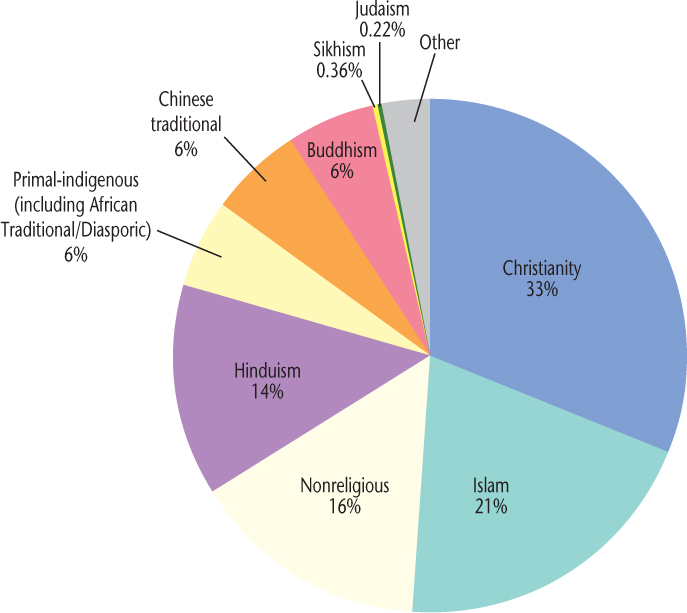

Christianity, a proselytic faith, is the world’s largest religion, both in area covered and in number of adherents, claiming about a third of the global population (Figure 7.4). Christians are monotheistic, believing that God is a Trinity consisting of three persons: the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. Jesus Christ is believed to be the incarnate Son of God who was given to humankind for the sake of human redemption some 2000 years ago. Through Jesus’ death and resurrection, all of humanity is offered redemption from sin and provided eternal life in heaven and a relationship with God.

Thinking Geographically

Question 7.4

Why does Hinduism, an ethnic religion, have such a large number of adherents?

Christianity, Islam, and Judaism are the world’s three great monotheisms and share a common culture hearth in southwestern Asia (see Figure 7.12). All three religions venerate the patriarch Abraham and thus can be called Abrahamic religions. Because Judaism is the parent religion of Christianity, the two faiths share many elements, including the Torah, the first five books of what Christians call the Old Testament (which forms part of the Christian Bible or holy book); prayer; and a clergy. This is the basis for the term Judeo-Christian, which is used to describe beliefs and practices shared by the two faiths. Because Jesus was born into the Jewish faith, many Christians still accord Jews a special status as a chosen people and see Christianity as the natural continuation or fulfillment of Judaism.

179

Christianity has long been fragmented into separate branches (see Figure 7.2). The major division is three-fold, made up of Roman Catholics, Protestants, and Eastern Christians. Western Christianity, which now includes Catholics and Protestants, was initially identified with Rome and the Latin-speaking areas that are largely congruent with modern western Europe, whereas the Eastern Church dominated the Greek world from Constantinople (now the city of Istanbul, Turkey). Belonging to the Eastern group are the Armenian Church, reputedly the oldest in the Christian faith and today centered among a people of the Caucasus region; the Coptic Church, originally the religion of Christian Egyptians and still today a minority faith there, as well as being the dominant church among the highland people of Ethiopia; the Maronites, Semitic descendants of seventh-century heretics who disagreed with some of early Christianity’s beliefs and retreated to a mountain refuge in Lebanon (see Figure 7.3); the Nestorians, who live in the mountains of the Middle East and in India’s Kerala state; and Eastern Orthodoxy, originally centered in Greek-speaking areas. After converting many Slavic groups, Eastern Orthodoxy is today composed of a variety of national churches, such as Russian, Greek, Ukrainian, and Serbian Orthodoxy, with a collective membership of some 300 million (Figure 7.5).

Thinking Geographically

Question 7.5

How do the height and durability of this structure demonstrate its importance?

Western Christianity splintered, most notably with the emergence of Protestantism in the Reformation of the 1400s and 1500s. As with other religious reformation movements, Protestantism sought to overcome what were viewed to be wrong practices of Roman Catholicism, such as the need for priestly or saintly mediation between humans and God, while still staying within the general framework of Christianity. Since then, the Roman Catholic Church, which alone included 1.2 billion people at the end of 2010, or about 15 percent of humanity, has remained unified; but Protestantism, from its beginnings, tended to divide into a rich array of sects, which together have a total membership today of about 593 million worldwide.

179

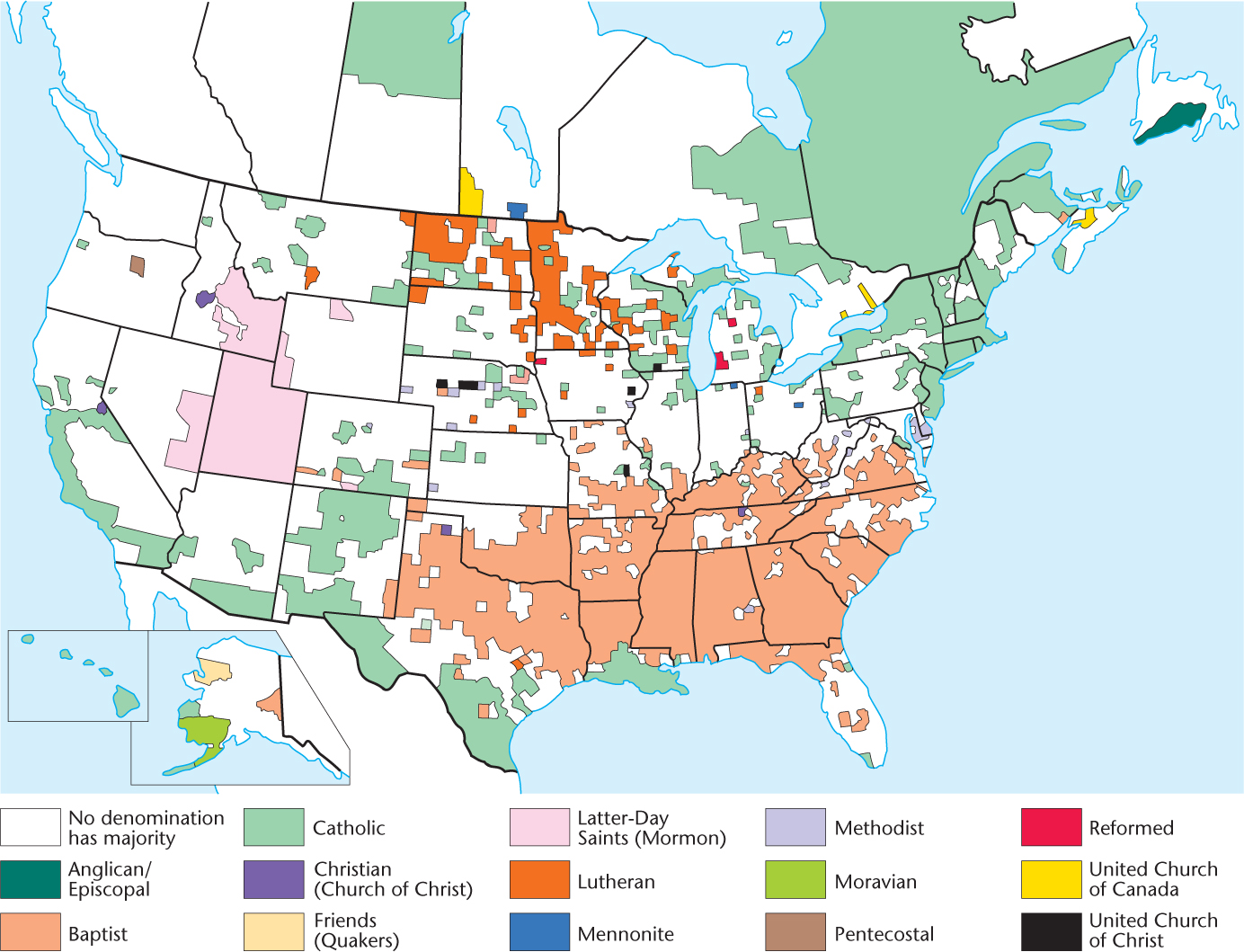

In the United States and Canada, the denominational map vividly reflects the fragmentation of Western Christianity and the resulting complex pattern of religious culture regions (Figure 7.6). Numerous denominations imported from Europe were later augmented by Christian denominations developed in America. The American frontier was a breeding ground for new religious groups, as individualistic pioneer sentiment found expression in splinter Protestant denominations. Today, in many parts of the country, even a relatively small community may contain the churches of half a dozen religious groups. As a result, we find today about 2000 different religious denominations and cults in the United States alone. In a broad Bible Belt across the South, Baptist and other conservative fundamentalist denominations dominate, and Utah is at the core of the Mormon realm. A Lutheran belt stretches from Wisconsin westward through Minnesota and the Dakotas, and Roman Catholicism dominates southern Louisiana, the southwestern borderland, and the heavily industrialized areas of the Northeast. The Midwest is a thoroughly mixed zone, although Methodism is the largest single denomination.

Thinking Geographically

Question 7.6

How does the pattern in the Midwest and Great Plains relate to the presence of ethnic islands? (See Figure 5.7)

179

Today, Christianity is geographically widespread and highly diverse in its local interpretation. Although it is not as fast-growing as Islam, intense missionary efforts strive to increase the number of adherents. Because of this proselytic work, Africa and Asia are the fastest-growing regions for Christianity.

Islam

Islam

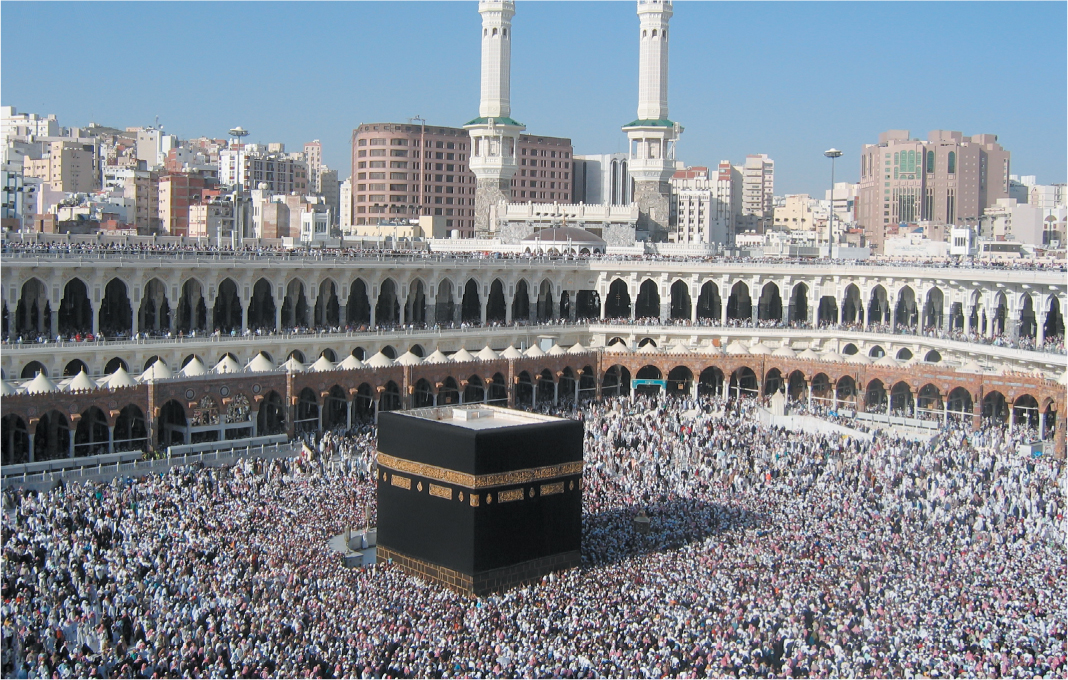

Islam, another great proselytic faith, claims approximately 1.6 billion followers, largely in the desert belt of Asia and northern Africa and in the humid tropics as far east as Indonesia and the southern Philippines (see Figures 7.2 and 7.4). Adherents of Islam, known as Muslims—literally, “those who submit to the will of God”—are monotheists and worship one absolute God known as Allah. Islam was founded by Muhammad, considered to be the last and most important in a long line of prophets. The word of Allah is believed to have been revealed to Muhammad by the angel Gabriel (Jibrail) beginning in a.d. 610 of the Christian calendar in the Arabian city of Mecca (Figure 7.7). The Qur’an (Koran), Islam’s holy book, is the text of these revelations and also serves as the basis of Islamic law, or sharia. Most Muslims consider both Jews and Christians to be, like themselves, “people of the Book,” and all three religions share beliefs in heaven, hell, and the resurrection of the dead. Many biblical figures familiar to Jews and Christians, such as Moses, Abraham, Mary, and Jesus, are also venerated as prophets in Islam. Adherents to Islam are expected to profess belief in Allah, the one God whose prophet was Muhammad; pray five times daily at established times; give alms, or zakat, to the poor; fast from dawn to sunset in the holy month of Ramadan; and make at least one pilgrimage, if possible, to the sacred city of Mecca in Saudi Arabia. These duties are known as the Five Pillars of the faith.

Thinking Geographically

Question 7.7

How would gatherings like this help to spread ideas, as well as diseases?

Although not as severely fragmented as Christianity, Islam, too, has split into separate groups. Two major divisions prevail. Shiite Muslims, 5 to 20 percent of the Islamic total in diverse subgroups (based on differing estimates), form the majority in Iran and Iraq. Shiites believe that Ali, who was Muhammad’s son-in-law, should have succeeded Muhammad. Sunni Muslims, who represent the Islamic orthodoxy (the word Sunni comes from sunnah, meaning tradition), form the large majority worldwide (see Figure 7.2). Islam has not undergone a reformation parallel to that undergone by Christianity with Protestantism. However, liberal movements within Sunni and Shiite Islam do have reformation as their goal.

Islam’s strength is greatest in the Arabic-speaking lands in Southwest Asia and North Africa, but the world’s largest Islamic population is found in Indonesia. Other large clusters live in Pakistan, India, Bangladesh, and western China. Because of successful conversion efforts in non-Muslim areas and high birth rates in predominantly Muslim areas, Islam is the fastest-growing world religion.

Hinduism

Hinduism

Hinduism, a religion closely tied to India and its ancient culture, claims about 900 million to 1 billion adherents (see Figures 7.2 and 7.4). Hinduism is a decidedly polytheistic religion. Although Hindus recognize one supreme god, Brahman, it is his many manifestations that are worshipped directly. Some principal Hindu deities include Vishnu, Shiva, and the mother goddess Devi. Ganesha, the elephant-headed god depicted in Figure 7.8 , is often revered by Hindu university students because Ganesha is the god of wisdom, intelligence, and education. Believing that no one faith has a monopoly on the truth, most Hindus are notably tolerant of other religions.

Thinking Geographically

Question 7.8

What other examples can you cite of students’ regard for a figure, whether religious or other, in their quest for success?

179

Hindus strive to locate the harmonious and eternal truth, dharma, that is within each human being. Social divisions, or castes, separate Hindu society into four major categories, or varna, based on occupational categories: priests (Brahmins), warriors (Kshatriyas), merchants and artisans (Vaishyas), and workers (Shudras). Castes are related to dharma inasmuch as dharma implies a set of rules for each varna that regulate their behaviors with regard to eating, marriage, and use of space. All Hindus also share a belief in reincarnation, the idea that although the physical body may die, the soul lives on and is reborn in another body. Related to this is the notion of karma. Karma can be viewed almost as a causal law, which holds that what an individual experiences in this life is a direct result of that individual’s thoughts and deeds in a past life. Likewise, all thoughts and deeds, both good and bad, affect an individual’s future lives. Ultimately moksha, or liberation of the soul from the cycle of death and rebirth, will occur when the worldly bonds of the material self fall away and one’s pure essence is freed. Ahimsa, or the principle of nonviolence, involves veneration of all forms of life. This implies a principle of noninjury to all sentient creatures, which is why many Hindus are vegetarians.

Hinduism has splintered into diverse groups, some of which are so distinctive as to be regarded as separate religions. Jainism, for instance, is an ancient outgrowth of Hinduism, claiming perhaps 6 million adherents, almost all of whom live in India, and traces its roots back more than 25 centuries. Although they reject Hindu scriptures, rituals, and priesthood, the Jains share the Hindu belief in ahimsa and reincarnation. Jains adhere to a strict asceticism, a practice involving self-denial and austerity. For example, they practice veganism, a form of vegetarianism that prohibits the consumption of all animal-based products, including milk and eggs. Sikhism, by contrast, arose much later, in the 1500s, in an attempt to unify Hinduism and Islam. Centered in the Punjab state of northwestern India, where the Golden Temple at Amritsar serves as the principal shrine, Sikhism has an estimated 30 million followers. Sikhs are monotheistic and have their own holy book, the Adi Granth.

No standard set of beliefs prevails in Hinduism, and the faith takes many local forms. Hinduism includes very diverse peoples. This is partly a result of its former status as a proselytic religion. A Hindu majority on the Indonesian island of Bali suggests the religion’s former missionary activity (Figure 7.9). Today, most Hindus consider their religion an ethnic one, whereby one is acculturated into the Hindu community by birth; however, conversion to Hinduism is also allowed.

Thinking Geographically

Question 7.9

What other examples can you cite of a religion that formerly had a widespread following in an area but now exists only in pockets?

Buddhism

Buddhism

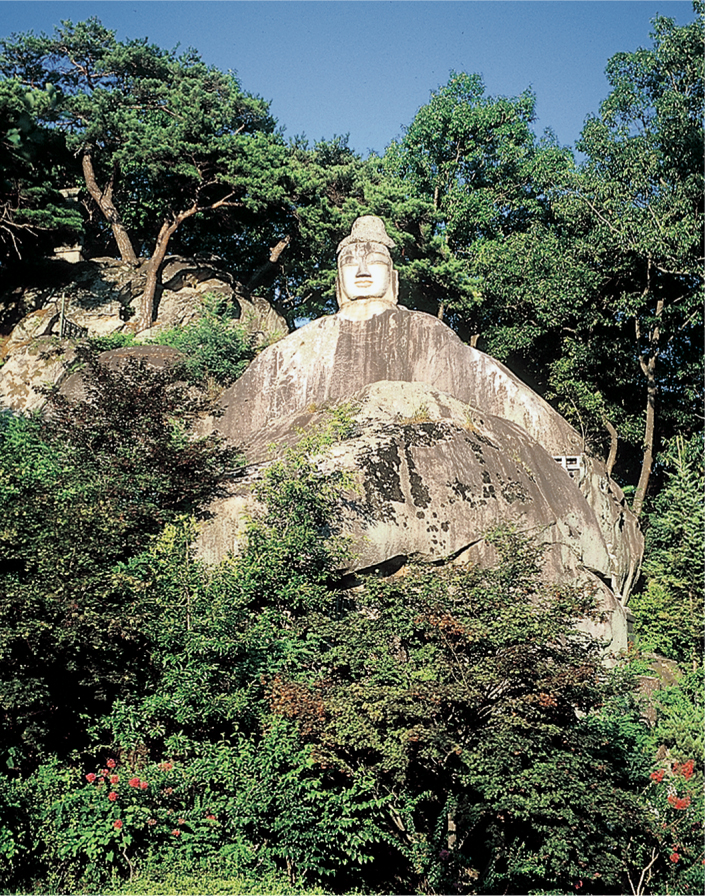

Hinduism is the parent religion of Buddhism, which began 25 centuries ago as a reform movement based on the teachings of Prince Siddhartha Gautama, “the awakened one” (Figure 7.10 , page 188). He promoted the four “noble truths”: life is full of suffering, desire is the cause of this suffering, cessation of suffering comes with the quelling of desire, and an “Eight-Fold Path” of proper personal conduct and meditation permits the individual to overcome desire. The resultant state of enlightenment is known as nirvana. Those few individuals who achieve nirvana are known as Buddhas. The status of Buddha is open to anyone regardless of social status, gender, or age. Because Buddhism derives from Hinduism, the two religions share many beliefs, such as dharma, reincarnation, and ahimsa. Buddhism and its parent religion, Hinduism, as well as the related faiths Jainism and Sikhism, are known as Dharmic religions.

Thinking Geographically

Question 7.10

From where would Buddhism have diffused to Korea?

179

Today, Buddhism is the most widespread religion in South and East Asia, dominating a culture region stretching from Sri Lanka to Japan and from Mongolia to Vietnam. In the process of its proselytic spread, particularly in China and Japan, Buddhism fused with native ethnic religions such as Confucianism, Taoism, and Shinto (sometimes called Shintoism) to form syncretic faiths that fall into the Mahayana division of Buddhism. Southern, or Theravada, Buddhism, dominant in Sri Lanka and mainland Southeast Asia, retains the greatest similarity to the religion’s original form, whereas a variation known as Tantrayana, or Lamaism, prevails in Tibet and Mongolia (see Figure 7.2). Buddhism’s tendency to merge with native religions, particularly in China, makes it difficult to determine the number of its adherents. Many estimates put the number of Buddhists at about 400 million. Although Buddhism in China has become mingled with local faiths to become part of a composite ethnic religion, elsewhere it remains one of the three great proselytic religions in the world, along with Christianity and Islam.

179

Taoic Religions

Taoic Religions

Confucianism, Shinto, and Taoism together make up the faiths that center on Tao, or the force that balances and orders the universe. Derived from the teachings of philosopher Kong Fu-tzu (551–479 b.c.), Confucianism was later promoted by China’s Han dynasty (206 b.c.–a.d. 220) as the official state philosophy. Thus, it has bureaucratic, ethical, and hierarchical overtones that have led some to question whether it is more a way of life than a religion in the proper sense. In China, Confucianism’s formalism is balanced by Taoism’s romanticism. Taoism, both an established religion and a philosophy, emphasizes the dynamic balance depicted by the Chinese yin/yang symbol. The “three jewels of Tao” are humility, compassion, and moderation. Shinto was once the state religion of Japan. Shinto has long been blended with Buddhism, as well as infused with a Confucian-derived legal system, but at its core Shinto is an animistic religion (see next section). Because Tao is found in nature, there is some overlap with the animistic faiths discussed next. In addition, because of their fluid nature, Taoic religions tend toward syncretism and have blended with other faiths, particularly Buddhism. People may simultaneously practice elements of all of these faiths. For these reasons, it is difficult to provide an exact number of adherents, although estimates hold there to be about 400 billion to 500 billion. Taoic religions center on East Asia (see Figure 7.2).

Animism/Shamanism

Animism/Shamanism

animist An adherent of animism, the idea that souls or spirits exist not only in humans but also in animals, plants, rocks, natural phenomena such as thunder, geographic features such as mountains or rivers, or other entities of the natural environment.

Peoples in diverse parts of the world often retain indigenous religions and are usually referred to collectively as animists (Figure 7.11). For the most part animists do not form organized or recognized religious groups but instead practice as ethnic religions common to clans or tribes. In addition, most animists follow oral, rather than written, traditions and thus do not have holy books. A tribal religious figure, called by some a shaman, usually serves as an intermediary between the people and the spirits.

Thinking Geographically

Question 7.11

What appeal do animistic religions have for modern people?

Currently numbering perhaps 230 million to 240 million, animists believe that nonhuman beings and inanimate objects possess spirits or souls. These spirits are believed to live in rocks and rivers, on mountain peaks and celestial bodies, in forests and swamps, and even in everyday objects. As such, objects are considered to be alive, and depending on the local beliefs, objects and animals may assume human forms or engage in human activities such as speech. For some animists, the objects in question do not actually possess spirits but rather are valued because they have a particular potency to serve as a link between a person and the omnipresent god. Followers of Wicca, a contemporary neopagan religion derived from pre-Christian European practices of reverence for the mother goddess and the horned god, worship the god and goddess who are thought to inhabit everything. Ritual tools used by Wiccans include the athame (dagger), boline (knife), and besom (broom), which are used in ceremonies to direct energy as practitioners communicate with the god and goddess.

Animistic elements can also pervade established religions. Japanese Shinto adherents worship kami, or spirits, that inhabit natural objects such as waterfalls and mountains. We should not classify such systems of belief as primitive or simple, because they can be extraordinarily complex. Even in places such as the United States, where the majority of the inhabitants would not see themselves as animists, such beliefs are pervasive. For example, many people in the United States believe that their pets possess souls that ascend to heaven on death.

179