Consumer Surplus, Producer Surplus, and Efficiency

Markets are a remarkably effective way to organize economic activity: under the right conditions, they can make society as well off as possible given the available resources. The concepts of consumer and producer surplus can help us deepen our understanding of why this is so.

The Gains from Trade

Let’s return to the market for used textbooks, but now consider a much bigger market—

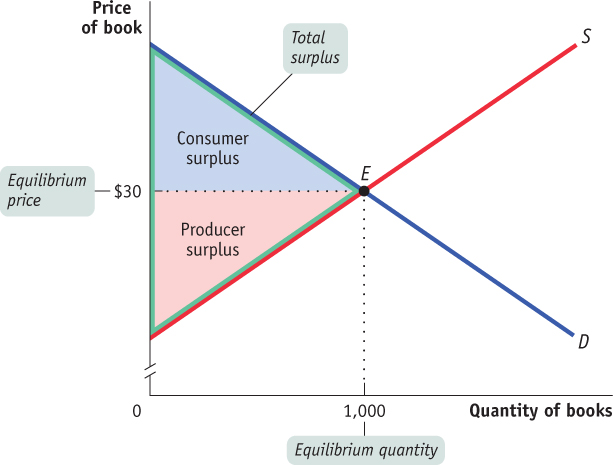

| Figure 50.1 | Total Surplus |

Total surplus is the total net gain to consumers and producers from trading in a market. It is the sum of producer and consumer surplus.

As we have drawn the curves, the market reaches equilibrium at a price of $30 per book, and 1,000 books are bought and sold at that price. The two shaded triangles show the consumer surplus (blue) and the producer surplus (pink) generated by this market. The sum of consumer and producer surplus, the total net gain to consumers and producers from trading in a market, is known as total surplus.

The striking thing about this picture is that both consumers and producers gain—

But are we as well off as we could be? This brings us to the question of the efficiency of markets.

The Efficiency of Markets

A market is efficient if, once the market has produced its gains from trade, there is no way to make some people better off without making other people worse off. Note that market equilibrium is just one way of deciding who consumes a good and who sells a good. To better understand how markets promote efficiency, let’s examine some alternatives. Consider the example of kidney transplants discussed earlier in an FYI box. There is no market for kidneys, and available kidneys currently go to whoever has been on the waiting list the longest. Of course, those who have been waiting the longest aren’t necessarily those who would benefit the most from a new kidney.

Similarly, imagine a committee charged with improving on the market equilibrium by deciding who gets and who gives up a used textbook. The committee’s ultimate goal would be to bypass the market outcome and come up with another arrangement that would increase total surplus.

Let’s consider three approaches the committee could take:

It could reallocate consumption among consumers.

It could reallocate sales among sellers.

It could change the quantity traded.

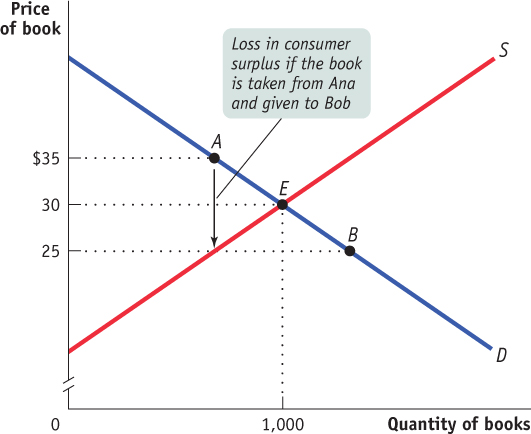

The Reallocation of Consumption Among Consumers The committee might try to increase total surplus by selling the used books to different consumers. Figure 50.2 shows why this will result in lower surplus compared to the market equilibrium outcome. Points A and B show the positions on the demand curve of two potential buyers of used books, Ana and Bob. As we can see from the figure, Ana is willing to pay $35 for a book, but Bob is willing to pay only $25. Since the market equilibrium price is $30, under the market outcome Ana gets a book and Bob does not.

| Figure 50.2 | Reallocating Consumption Lowers Consumer Surplus |

Now suppose the committee reallocates consumption. This would mean taking the book away from Ana and giving it to Bob. Since the book is worth $35 to Ana but only $25 to Bob, this change reduces total consumer surplus by $35 – $25 = $10. Moreover, this result doesn’t depend on which two students we pick. Every student who buys a book at the market equilibrium price has a willingness to pay of $30 or more, and every student who doesn’t buy a book has a willingness to pay of less than $30. So reallocating the good among consumers always means taking a book away from a student who values it more and giving it to one who values it less. This necessarily reduces total consumer surplus.

AP® Exam Tip

Anything that prevents the sale of a unit that would have occurred in market equilibrium reduces total surplus.

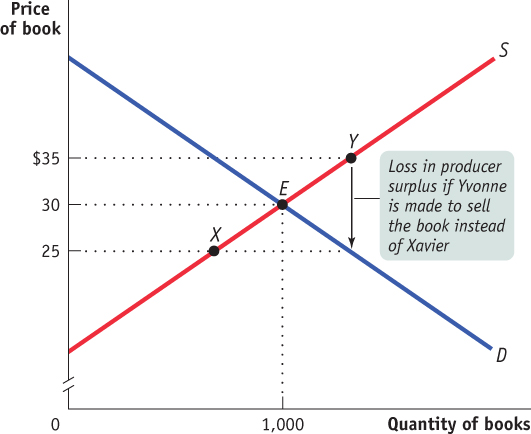

The Reallocation of Sales Among Sellers The committee might try to increase total surplus by altering who sells their books, taking sales away from sellers who would have sold their books in the market equilibrium and instead compelling those who would not have sold their books in the market equilibrium to sell them. Figure 50.3 shows why this will result in lower surplus. Here points X and Y show the positions on the supply curve of Xavier, who has a cost of $25, and Yvonne, who has a cost of $35. At the equilibrium market price of $30, Xavier would sell his book but Yvonne would not sell hers. If the committee reallocated sales, forcing Xavier to keep his book and Yvonne to sell hers, total producer surplus would be reduced by $35 – $25 = $10. Again, it doesn’t matter which two students we choose. Any student who sells a book at the market equilibrium price has a lower cost than any student who keeps a book. So reallocating sales among sellers necessarily increases total cost and reduces total producer surplus.

| Figure 50.3 | Reallocating Sales Lowers Producer Surplus |

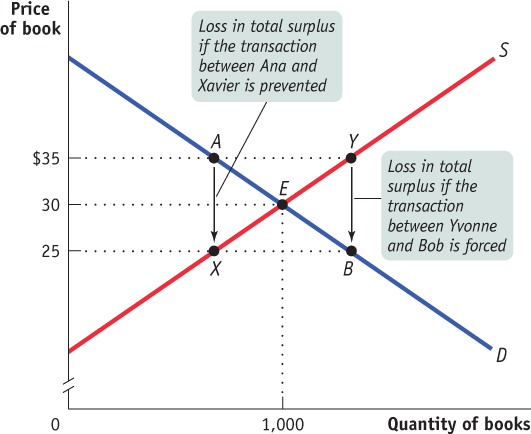

Changes in the Quantity Traded The committee might try to increase total surplus by compelling students to trade either more books or fewer books than the market equilibrium quantity. Figure 50.4 shows why this will result in lower surplus. It shows all four students: potential buyers Ana and Bob, and potential sellers Xavier and Yvonne. To reduce sales, the committee will have to prevent a transaction that would have occurred in the market equilibrium—

| Figure 50.4 | Changing the Quantity Lowers Total Surplus |

Finally, the committee might try to increase sales by forcing Yvonne, who would not have sold her book in the market equilibrium, to sell it to someone like Bob, who would not have bought a book in the market equilibrium. Because Yvonne’s cost is $35, but Bob is only willing to pay $25, this transaction reduces total surplus by $10. And once again it doesn’t matter which two students we pick—

The key point is that once this market is in equilibrium, there is no way to increase the gains from trade. Any other outcome reduces total surplus. We can summarize our results by stating that an efficient market performs four important functions:

It allocates consumption of the good to the potential buyers who most value it, as indicated by the fact that they have the highest willingness to pay.

It allocates sales to the potential sellers who most value the right to sell the good, as indicated by the fact that they have the lowest cost.

It ensures that every consumer who makes a purchase values the good more than every seller who makes a sale, so that all transactions are mutually beneficial.

It ensures that every potential buyer who doesn’t make a purchase values the good less than every potential seller who doesn’t make a sale, so that no mutually beneficial transactions are missed.

There are three caveats, however. First, although a market may be efficient, it isn’t necessarily fair. In fact, fairness, or equity, is often in conflict with efficiency. We’ll discuss this next.

The second caveat is that markets sometimes fail. Under some well-

Third, even when the market equilibrium maximizes total surplus, this does not mean that it results in the best outcome for every individual consumer and producer. Other things equal, each buyer would like to pay a lower price and each seller would like to receive a higher price. So if the government were to intervene in the market—

Equity and Efficiency

AP® Exam Tip

Be prepared to identify and provide examples of various taxes for the AP® exam. You may also be asked to determine how a change in taxes affects consumer and producer surplus.

It’s easy to get carried away with the idea that markets are always good and that economic policies that interfere with efficiency are bad. But that would be misguided because there is another factor to consider: society cares about equity, or what’s “fair.” There is often a trade-

In fact, the debate about equity and efficiency is at the core of most debates about taxation. Proponents of taxes that redistribute income from the rich to the poor often argue for the fairness of such redistributive taxes. Opponents of taxation often argue that phasing out certain taxes would make the economy more efficient.

A progressive tax rises more than in proportion to income.

A regressive tax rises less than in proportion to income.

A proportional tax rises in proportion to income.

Because taxes are ultimately paid out of income, economists classify taxes according to how they vary with the income of individuals. A tax that rises more than in proportion to income, so that high-