Dealing with a Natural Monopoly

Breaking up a monopoly that isn’t natural is clearly a good idea: the gains to consumers outweigh the loss to the producer. But it’s not so clear whether a natural monopoly, one in which large producers have lower average total costs than small producers, should be broken up, because this would raise average total cost. For example, a town government that tried to prevent a single company from dominating local gas supply—

Yet even in the case of a natural monopoly, a profit-

What can public policy do about this? There are two common answers.

Public Ownership

With public ownership of a monopoly, the good is supplied by the government or by a firm owned by the government.

In many countries, the preferred answer to the problem of natural monopoly has been public ownership. Instead of allowing a private monopolist to control an industry, the government establishes a public agency to provide the good and protect consumers’ interests.

The advantage of public ownership, in principle, is that a publicly owned natural monopoly can set prices based on the criterion of efficiency rather than profit maximization. In a perfectly competitive industry, profit-

Experience suggests, however, that public ownership as a solution to the problem of natural monopoly often works badly in practice. One reason is that publicly owned firms are often less eager than private companies to keep costs down or offer high-

Regulation

Price regulation limits the price that a monopolist is allowed to charge.

In the United States, the more common answer has been to leave the industry in private hands but subject it to regulation. In particular, most local utilities, like electricity, telephone service, natural gas, and so on, are covered by price regulation that limits the prices they can charge.

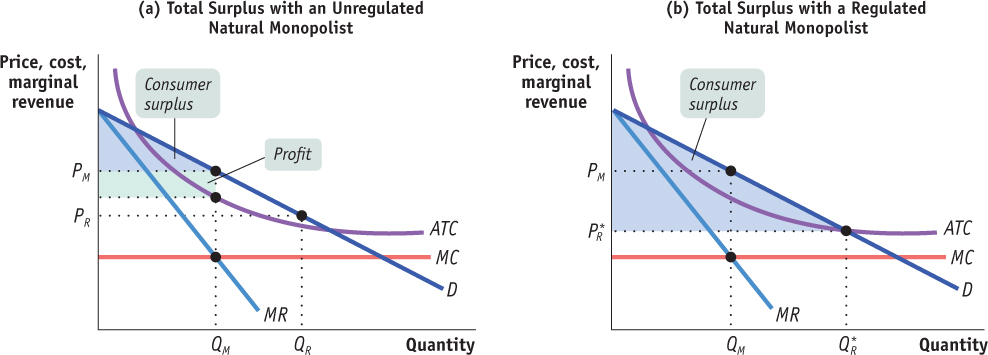

Figure 62.2 shows an example of price regulation of a natural monopoly—

| Figure 62.2 | Unregulated and Regulated Natural Monopoly |

Panel (a) illustrates a case of natural monopoly without regulation. The unregulated natural monopolist chooses the monopoly output QM and charges the price PM. Since the monopolist receives a price greater than average total cost, she or he earns a profit, represented by the green-

Now suppose that regulators impose a price ceiling on local gas deliveries—

AP® Exam Tip

You may be asked to explain what happens to consumer surplus, producer surplus, and deadweight loss when a monopoly is regulated. Remember that a regulated price equal to the average total cost is the lowest price that would not cause the firm to take losses and eventually close.

Does the company have an incentive to produce that quantity? Yes. If the price the monopolist can charge is fixed at PR by regulators, the firm can sell any quantity between zero and QR for the same price, PR. Because it doesn’t have to lower its price to sell more (up to QR), there is no price effect to bring marginal revenue below price, so the regulated price becomes the marginal revenue for the monopoly just like the market price is the marginal revenue for a perfectly competitive firm. With marginal revenue being above marginal cost and price exceeding average cost, the firm expands output to meet the quantity demanded, QR. This policy has appeal because at the regulated price, the monopolist produces more at a lower price.

If regulators pursued allocative efficiency by setting a price ceiling equal to marginal cost, the monopolist would not be willing to produce at all in the long run, because it would be producing at a loss. That is, the price ceiling has to be set high enough to allow the firm to cover its average total cost. Panel (b) shows a situation in which regulators have pushed the price down as far as possible, at the level where the average total cost curve crosses the demand curve. At any lower price the firm loses money. The price here, P*R, is the best regulated price: the monopolist is just willing to operate and produces Q*R, the quantity demanded at that price. Consumers and society gain as a result.

The welfare effects of this regulation can be seen by comparing the shaded areas in the two panels of Figure 62.2. Consumer surplus is increased by the regulation, with the gains coming from two sources. First, profit is eliminated and added instead to consumer surplus. Second, the larger output and lower price leads to an overall welfare gain—

Must Monopoly Be Controlled?

Sometimes the cure is worse than the disease. Some economists have argued that the best solution, even in the case of a natural monopoly, may be to live with it. The case for doing nothing is that attempts to control monopoly, one way or another, will do more harm than good.

The following FYI describes the case of cable television, a natural monopoly that has been alternately regulated and deregulated as politicians change their minds about the appropriate policy.

Cable Dilemmas

Cable Dilemmas

Most price regulation in the United States goes back a long way: electricity, local phone service, water, and gas have been regulated in most places for generations. But cable television is a relatively new industry. Until the late 1970s, only rural areas too remote to support local broadcast stations were served by cable. After 1972, new technology and looser rules made it profitable to offer cable service to major metropolitan areas; new networks like HBO and CNN emerged to take advantage of the possibilities.

Until recently, local cable TV was a natural monopoly: running cable through a town entails large fixed costs that don’t depend on how many people actually subscribe. Having more than one cable company would involve a lot of wasteful duplication. But if the local cable company is a monopoly, should its prices be regulated?

At first, most local governments thought so, and cable TV was subject to price regulation. In 1984, however, Congress passed a law prohibiting most local governments from regulating cable prices. (The law was the result both of widespread skepticism about whether price regulation was actually a good idea and of intensive lobbying by the cable companies.)

After the law went into effect, however, cable television rates increased sharply. The resulting consumer backlash led to a new law, in 1992, which once again allowed local governments to set limits on cable prices.

Was the second round of regulation a success? As measured by the prices of “basic” cable service, it was: after rising rapidly during the period of deregulation, the cost of basic service leveled off.

However, price regulation in cable applies only to “basic” service. Cable operators can try to evade the restrictions by charging more for premium channels like HBO or by offering fewer channels in the “basic” package. So some skeptics have questioned whether current regulation has actually been effective.

Yet technological change has begun providing relief to consumers in some areas. Although cable TV is a natural monopoly, there is now another means of delivering video programs to homes: over a high-