14.3 Determining the Money Supply

Without banks, there would be no chequeable deposits, so the quantity of currency in circulation would equal the money supply. In that case, the money supply would be solely determined by whoever controls government minting and printing presses. But banks do exist, and through their creation of chequeable deposits they affect the money supply in two ways. First, banks remove some currency from circulation: dollar bills that are sitting in bank vaults, as opposed to sitting in people’s wallets, aren’t part of the money supply. Second, and much more importantly, banks create money by accepting deposits and making loans—

How Banks Create Money

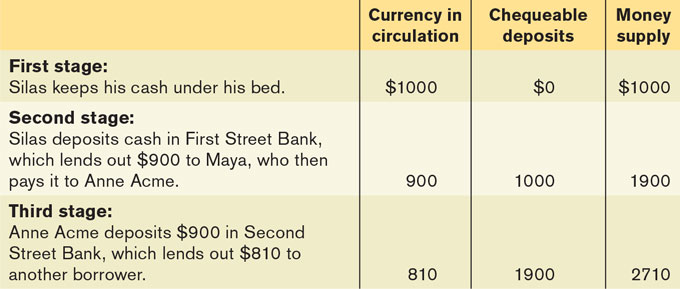

To see how banks create money, let’s examine what happens when someone decides to deposit currency in a bank. Consider the example of Silas, a miser, who keeps a shoebox full of cash under his bed. Suppose Silas realizes that it would be safer, as well as more convenient, to deposit that cash in the bank and to use his debit card when shopping. Assume that he deposits $1000 into a chequeable account at First Street Bank. What effect will Silas’s actions have on the money supply?

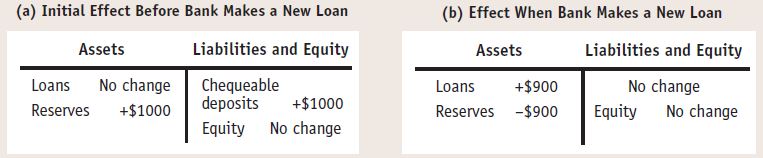

Figure 14-5a shows the initial effect of his deposit. First Street Bank credits Silas with $1000 in his account, so the economy’s chequeable deposits rise by $1000. Meanwhile, Silas’s cash goes into the vault, raising First Street’s reserves by $1000 as well.

This initial transaction has no effect on the money supply. Currency in circulation, part of the money supply, falls by $1000; chequeable deposits, also part of the money supply, rise by the same amount.

But this is not the end of the story because First Street Bank can now lend out part of Silas’s deposit. Assume that it holds 10% of Silas’s deposit—

So by putting $900 of Silas’s cash back into circulation by lending it to Maya, First Street Bank has, in fact, increased the money supply. That is, the sum of currency in circulation and chequeable deposits has risen by $900 compared to what it had been when Silas’s cash was still under his bed. Although Silas is still the owner of $1000, now in the form of a chequeable deposit, Maya has the use of $900 in cash from her borrowings.

And this may not be the end of the story. Suppose that Maya uses her cash to buy a television and a DVD player from Acme Merchandise. What does Anne Acme, the store’s owner, do with the cash? If she holds on to it, the money supply doesn’t increase any further. But suppose she deposits the $900 into a chequeable deposit—

Assume that Second Street Bank, like First Street Bank, keeps 10% of any bank deposit in reserves and lends out the rest. Then it will keep $90 in reserves and lend out $810 of Anne’s deposit to another borrower, further increasing the money supply.

Table 14-1 shows the process of money creation we have described so far. At first the money supply consists only of Silas’s $1000. After he deposits the cash into a chequeable deposit and the bank makes a loan, the money supply rises to $1900. After the second deposit and the second loan, the money supply rises to $2710. And the process will, of course, continue from there. (Although we have considered the case in which Silas places his cash in a chequeable deposit, the results would be the same if he put it into any type of near-

This process of money creation may sound familiar. In Chapter 11 we described the multiplier process: an initial increase in real GDP leads to a rise in consumer spending, which leads to a further rise in real GDP, which leads to a further rise in consumer spending, and so on. What we have here is another kind of multiplier—

Reserves, Bank Deposits, and the Money Multiplier

In tracing out the effect of Silas’s deposit in Table 14-1, we assumed that the funds a bank lends out always end up being deposited either in the same bank or in another bank—

In reality, some of these loaned funds may be held by borrowers in their wallets and not deposited in a bank, meaning that some of the loaned amount “leaks” out of the banking system. Such leaks reduce the size of the money multiplier, just as leaks of real income into savings reduce the size of the real GDP multiplier. (Bear in mind, however, that the “leak” here comes from the fact that borrowers keep some of their funds in currency, rather than the fact that consumers save some of their income.)

Excess reserves are a bank’s reserves over and above its desired reserves.

But let’s set that complication aside for a moment and consider how the money supply is determined in a “chequeable-

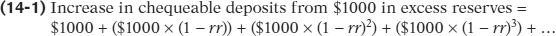

Now suppose that for some reason a bank suddenly finds itself with $1000 in excess reserves. What happens? The answer is that the bank will lend out that $1000, which will end up as a chequeable deposit somewhere in the banking system, launching a money multiplier process very similar to the process shown in Table 14-1.

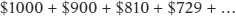

In the first stage, the bank lends out its excess reserves of $1000, which becomes a chequeable deposit somewhere. The bank that receives the $1000 deposit keeps 10%, or $100, as reserves and lends out the remaining 90%, or $900, which again becomes a chequeable deposit somewhere. The bank receiving this $900 deposit again keeps 10%, which is $90, as reserves and lends out the remaining $810. The bank receiving this $810 keeps $81 in reserves and lends out the remaining $729, and so on. As a result of this process, the total increase in chequeable deposits is equal to a sum that looks like:

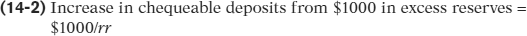

We’ll use the symbol rr for the reserve ratio. More generally, the total increase in chequeable deposits that is generated when a bank lends out $1000 in excess reserves is:

As we saw in Chapter 11, an infinite series of this form can be simplified to:

Given a reserve ratio of 10%, or 0.1, a $1000 increase in excess reserves will increase the total value of chequeable deposits by $1000/0.1 = $10 000. In fact, in a chequeable-

The Money Multiplier in Reality

In reality, the determination of the money supply is more complicated than our simple model suggests because it depends not only on the ratio of reserves to bank deposits but also on the fraction of the money supply that individuals choose to hold in the form of currency. In fact, we already saw this in our example of Silas depositing the cash under his bed: when he chose to hold a chequeable deposit instead of currency, he set in motion an increase in the money supply.

The monetary base is the sum of currency in circulation and bank reserves.

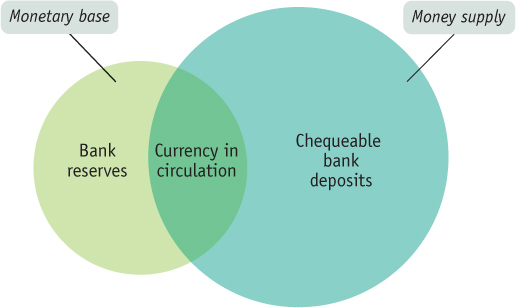

To define the money multiplier in practice, it’s important to recognize that the Bank of Canada controls the sum of bank reserves and currency in circulation, called the monetary base, but it does not control the allocation of that sum between bank reserves and currency in circulation. Consider Silas and his deposit one more time: by taking the cash from under his bed and depositing it in a bank, he reduced the quantity of currency in circulation but increased bank reserves by an equal amount—

The monetary base is different from the money supply in two ways. First, bank reserves, which are part of the monetary base, aren’t considered part of the money supply. A $10 bill in someone’s wallet is considered money because it’s available for an individual to spend, but a $10 bill held as bank reserves in a bank vault or deposited at the Bank of Canada isn’t considered part of the money supply because it’s not available for spending. Second, chequeable deposits, which are part of the money supply because they are available for spending, aren’t part of the monetary base.

Figure 14-6 shows the two concepts schematically. The circle on the left represents the monetary base, consisting of bank reserves plus currency in circulation. The circle on the right represents the money supply, consisting mainly of currency in circulation plus chequeable or near-

The money multiplier is the ratio of the money supply to the monetary base.

Now we can formally define the money multiplier: it’s the ratio of the money supply to the monetary base. The (actual) money multiplier in Canada, using M1 as our measure of money, has fluctuated between 6.1 and 9.1 from August 2003 to August 2012, with the average being 7.3. On the other hand, using M2+ as our measure of the money supply, during this period, the money multiplier fluctuated between 18.9 and 22.8, with the average being 20.7. How do these numbers compare with our money multiplier formula? The voluntary reserve ratio in Canada during the same time horizon was about 0.04 (i.e., 4%). That implies a money multiplier in a chequeable-

That describes what happened during normal times, when the economy was not in a crisis. But during “abnormal” times, the money multiplier can fall dramatically. Take the U.S. as an example. Usually the money multiplier in the United States, using M1 as the measure of money, fluctuates between 1.5 and 3.0. During the U.S. recession of 2007–2009, it fell to about 0.7. What happened? As we explain later in this chapter, and at greater length in Chapter 17, a very abnormal situation developed when Lehman Brothers, a key financial institution in the U.S., failed in September 2008. The American banks, seeing few opportunities for safe, profitable lending, began parking large sums at the Federal Reserve, the U.S. central bank, in the form of deposits—

MULTIPLYING MONEY DOWN

In our hypothetical example illustrating how banks create money, we described Silas the miser taking the currency from under his bed and turning it into a chequeable deposit. This led to an increase in the money supply, as banks engaged in successive waves of lending backed by Silas’s funds. It follows that if something happened to make Silas revert to old habits, taking his money out of the bank and putting it back under his bed, the result would be less lending and, ultimately, a decline in the money supply. That’s exactly what happened as a result of the bank runs of the 1930s in the U.S.

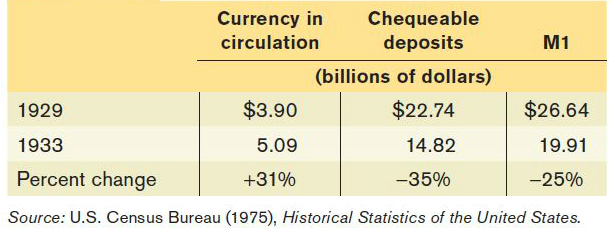

Table 14-2 shows what happened between 1929 and 1933, as bank failures shook the public’s confidence in the American banking system. The second column shows the public’s holdings of currency. This increased sharply, as many Americans decided that money under the bed was safer than money in the bank after all. The third column shows the value of chequeable deposits. This fell sharply, through the multiplier process we have just analyzed, when individuals pulled their cash out of banks. Loans also fell because banks that survived the waves of bank runs increased their excess reserves, just in case another wave began. The fourth column shows the value of M1, the first of the monetary aggregates we described earlier. It fell sharply because the total reduction in chequeable or near-

Quick Review

Banks create money when they lend out excess reserves, generating a multiplier effect on the money supply.

In a chequeable-

deposits- only system, the money supply would be equal to bank reserves divided by the reserve ratio. In reality, however, the public holds some funds as cash rather than in chequeable deposits, which reduces the size of the multiplier. The monetary base, equal to bank reserves plus currency in circulation, overlaps but is not equal to the money supply. The money multiplier is equal to the money supply divided by the monetary base.

Check Your Understanding 14-3

CHECK YOUR UNDERSTANDING 14-3

Assume that total reserves are equal to $200 and total chequeable deposits are equal to $1000. Also assume that the public does not hold any currency. Now suppose that the required reserve ratio falls from 20% to 10%. Trace out how this leads to an expansion in bank deposits.

Since they only have to hold $100 in reserves, instead of $200, banks now lend out $100 of their reserves. Whoever borrows the $100 will deposit it in a bank, which will lend out $100 × (1 – rr) = $100 × 0.9 = $90. Whoever borrows the $90 will put it into a bank, which will lend out $90 × 0.9 = $81, and so on. Overall, deposits will increase by $100/0.1 = $1000.

Take the example of Silas depositing his $1000 in cash into First Street Bank and assume that the required reserve ratio is 10%. But now assume that each time someone receives a bank loan, he or she keeps half the loan in cash. Trace out the resulting expansion in the money supply.

Silas puts $1000 in the bank, of which the bank lends out $1000 × (1 – rr) = $1000 × 0.9 = $900. Whoever borrows the $900 will keep $450 in cash and deposit $450 in a bank. The bank will lend out $450 × 0.9 = $405. Whoever borrows the $405 will keep $202.50 in cash and deposit $202.50 in a bank. The bank will lend out $202.50 × 0.9 = $182.25, and so on. Overall, this leads to an increase in deposits of $1000 + $450 + $202.50 + … But it decreases the amount of currency in circulation: the amount of cash is reduced by the $1000 Silas puts into the bank. This is offset, but not fully, by the amount of cash held by each borrower. The amount of currency in circulation therefore changes by –$1000 + $450 + $202.50 + … The money supply therefore increases by the sum of the increase in deposits and the change in currency in circulation, which is $1000 – $1000 + $450 + $450 + $202.50 + $202.50 + … and so on.