16.4 Deflation

Before World War II, deflation—a falling aggregate price level—

Why is deflation a problem? And why is it hard to end?

Debt Deflation

Deflation, like inflation, produces both winners and losers—

Debt deflation is the reduction in aggregate demand arising from the increase in the real burden of outstanding debt caused by deflation.

In a famous analysis at the beginning of the Great Depression, Irving Fisher (who first analyzed the Fisher effect of expected inflation on interest rates, described in Chapter 10) claimed that the effects of deflation on borrowers and lenders can worsen an economic slump. Deflation, in effect, takes real resources away from borrowers and redistributes them to lenders. Fisher argued that borrowers, who lose from deflation, are typically short of cash and will be forced to cut their spending sharply when their debt burden rises. Lenders, however, are unlikely to increase spending sharply when the values of the loans they own rise. The overall effect, said Fisher, is that deflation reduces aggregate demand, and the resulting leftward shift of the AD (aggregate demand) curve deepens the economic slump, which, in a vicious circle, may lead to further deflation. The effect of deflation in reducing aggregate demand, known as debt deflation, probably played a significant role in the Great Depression.

Effects of Expected Deflation

Like expected inflation, expected deflation affects the nominal interest rate. Look back at Figure 10-7, which demonstrated how expected inflation affects the equilibrium interest rate. In Figure 10-7, the equilibrium nominal interest rate is 4% if the expected inflation rate is 0%. Clearly, if the expected inflation rate is −3%—if the public expects deflation at 3% per year—the equilibrium nominal interest rate will be 1%.

But what would happen if the expected rate of inflation is −5%? Would the nominal interest rate fall to −1%, in which lenders are paying borrowers 1% on their debt? No. Nobody would lend money at a negative nominal rate of interest because they could do better by simply holding cash. This illustrates what economists call the zero bound on the nominal interest rate: it cannot go below zero.

There is a zero bound on the nominal interest rate: it cannot go below zero.

This zero bound can limit the effectiveness of monetary policy. Suppose the economy is depressed, with output below potential output and the unemployment rate above the natural rate. Normally the central bank can respond by cutting interest rates so as to increase aggregate demand. If the nominal interest rate is already zero, however, the central bank cannot push it down any further. Banks refuse to lend and consumers and firms refuse to spend because, with a negative inflation rate and a 0% nominal interest rate, holding cash yields a positive real return: with falling prices, a given amount of cash buys more over time. Any further increases in the monetary base will either be held in bank vaults or held as cash by individuals and firms, without being spent.

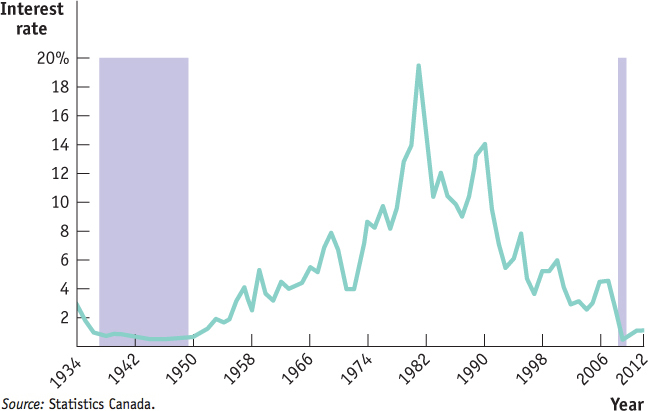

A situation in which conventional monetary policy to fight a slump—cutting interest rates—can’t be used because nominal interest rates are up against the zero bound is known as a liquidity trap. A liquidity trap can occur whenever there is a sharp reduction in demand for loanable funds—which is exactly what happened during the Great Depression. Figure 16-13 shows the interest rate on short-term Canadian government debt from 1934 to the end of 2012. As you can see, from the mid-1930s until World War II brought a full economic recovery, the Canadian economy was either close to or up against the zero bound. After World War II, when inflation became the norm around the world, the zero bound largely vanished as a problem as the public came to expect inflation rather than deflation.

Source: Statistics Canada.

The economy is in a liquidity trap when conventional monetary policy is ineffective because nominal interest rates are up against the zero bound.

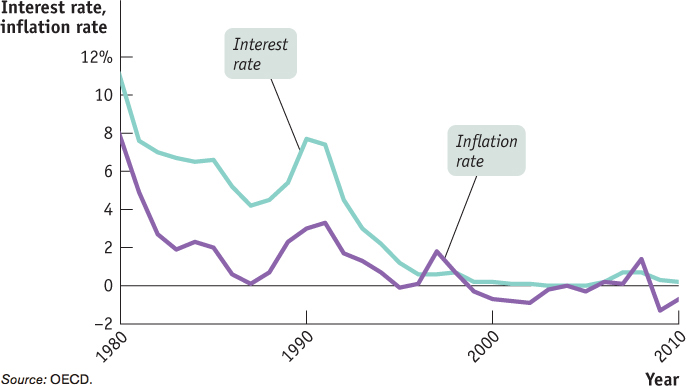

However, the recent history of the Japanese economy, shown in Figure 16-14, provides a modern illustration of the problem of deflation and the liquidity trap. Japan experienced a huge boom in the prices of both stocks and real estate in the late 1980s, then saw both bubbles burst. The result was a prolonged period of economic stagnation, the so-called Lost Decade, which gradually reduced the inflation rate and eventually led to persistent deflation. In an effort to fight the weakness of the economy, the Bank of Japan—the equivalent of the Bank of Canada—repeatedly cut interest rates. Eventually, it arrived at the ZIRP: the zero interest rate policy. The call money rate, the equivalent of the Bank of Canada’s bank rate, was literally set equal to zero. Because the economy was still depressed, it would have been desirable to cut interest rates even further. But that wasn’t possible: Japan was up against the zero bound.

Source: OECD.

In the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, the U.S. Federal Reserve also found itself up against the zero bound, with the interest rate on short-term U.S. government debt virtually at zero. As discussed in the following Economics in Action, this led to fears of a Japan-type trap and spurred the Fed to take some unconventional action.

THE U.S. DEFLATION SCARE OF 2010

Ever since the financial crisis of 2008, U.S. policy-makers have been worried about the possibility of “Japanification”—that is, they have worried that, like Japan since the 1990s, the United States might find itself stuck in a deflationary trap. Indeed, Ben Bernanke, the chairman of the U.S. Federal Reserve, studied Japan intensively before he went to the Fed and has sought to do better than his Japanese counterparts did.

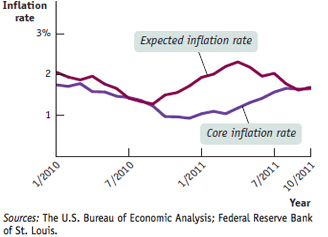

Sources: The U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis; Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

Fears of deflation were particularly intense in the summer and early fall of 2010. Figure 16-15 shows why, by tracking two numbers the Fed watches carefully when making policy. One of these numbers is the “core” inflation rate over the past year—the percentage rise in a measure of consumer prices (the personal consumption expenditure deflator) that excludes volatile food and energy prices. The Fed normally regards this core inflation rate as its best guide to underlying inflation and tries to keep it at around 2%. The other number is a measure of expected inflation derived by calculating the difference between the interest rate on ordinary government bonds and the rate on government bonds with the same term to maturity whose yield is protected against or indexed to inflation.

As you can see, by the late summer of 2010 both actual inflation and expected inflation were sliding to levels well below the Fed’s 2% target. Fed officials were worried, and they took action. In August 2010 Ben Bernanke gave a speech at the annual Fed meeting in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, signalling that he would take special actions to head off the deflationary threat. And in November the Fed, which normally buys only short-term government debt, began a program of long-term bond purchases, in the hope that this would give the economy a boost.

Figure 16-15 shows that Bernanke’s speech and the Fed’s action led to a major change in expectations, as investors’ fears of deflation ebbed. Actual inflation also picked up significantly.

What was far from clear, however, was whether the Fed had achieved more than a temporary reprieve. A year after Bernanke’s big speech, expected inflation was sagging again, and deflation fears were again on the rise.

Quick Review

Unexpected deflation helps lenders and hurts borrowers. This can lead to debt deflation, which has a contractionary effect on aggregate demand.

Deflation makes it more likely that interest rates will end up against the zero bound. When this happens, the economy is in a liquidity trap, and conventional monetary policy is ineffective.

Check Your Understanding 16-4

CHECK YOUR UNDERSTANDING 16-4

Why won’t anyone lend money at a negative nominal rate of interest? How can this pose problems for monetary policy?

If the nominal interest rate is negative, an individual is better off simply holding cash, which has a 0% nominal rate of return. If the options facing an individual are to lend and receive a negative nominal interest rate or to hold cash and receive a 0% nominal interest rate, the individual will hold cash. Such a scenario creates the possibility of a liquidity trap, in which monetary policy is ineffective because the nominal interest rate cannot fall below zero. Once the nominal interest rate falls to zero, further increases in the money supply will lead firms and individuals to simply hold the additional cash.

Licences to Print Money

People sometimes talk about profitable companies as having a “licence to print money.” Well, the British firm De La Rue actually does. In 1930, De La Rue, printer of items such as postage stamps, expanded into the money-printing business, producing banknotes for the then-government of China. Today it produces the currencies of about 150 countries.

De La Rue’s business received some unexpected attention in 2011 when Moammar Gadhafi, the dictator who had ruled Libya since 1969, was fighting to suppress a fierce popular uprising. To finance his efforts, he turned to seigniorage, ordering around $1.5 billion worth of Libyan dinars printed. But Libyan banknotes weren’t printed in Libya; they were printed in Britain at one of De La Rue’s facilities. The British Government, an enemy of the Gadhafi regime, seized the new banknotes before they could be flown to Libya, refusing to release them until Gadhafi had been overthrown.

Why do so many countries turn to private companies like De La Rue and its main rival, the German firm Giesecke and Devrient, to print their currencies? The short answer is that printing money isn’t as easy as it sounds: producing high-quality banknotes that are hard to counterfeit requires highly specialized equipment and expertise. Some nations, like China, Japan, and the United States, can easily afford to do this for themselves: U.S. currency is printed by the Bureau of Engraving and Printing, a division of the U.S. Treasury Department, on special paper produced by a private supplier. But many countries, even those with rich, advanced economies, feel they do better by turning to experts like De La Rue, which can include high-tech features like security threads and holography to fight counterfeiters.

Canada’s banknotes are produced by two private printers located in Ottawa. The Canadian Bank Note Company, a Canadian company, and BA International Inc., a division of Giesecke and Devrient, print all Canadian banknotes for the Bank of Canada. The Bank of Canada designs all the art and security features of the notes. To help prevent counterfeiting, Canada’s banknotes are now printed on polymer sheets using technology developed by Australia’s central bank.

Recently, De La Rue had problems with quality control: a scandal erupted in 2010, when it emerged that one of its plants had been producing defective security paper and that employees had covered up the problems. Nonetheless, many countries will surely continue relying on expert private firms to produce their currency.

QUESTIONS FOR THOUGHT

How can a government obtain revenue by printing money when someone else actually prints the money?

How can a government obtain revenue by printing money when someone else actually prints the money?

Why, exactly, would Gadhafi have resorted to the printing press in early 2011?

Why, exactly, would Gadhafi have resorted to the printing press in early 2011?

Were there risks to the Libyan economy in releasing those dinars to the new government?

Were there risks to the Libyan economy in releasing those dinars to the new government?