7.1 The National Accounts

Almost all countries calculate a set of numbers known as the national income and product accounts. In fact, the accuracy of a country’s accounts is a remarkably reliable indicator of its state of economic development—

The national income and product accounts, or national accounts, keep track of the flows of money between different sectors of the economy.

In Canada, these numbers are calculated by Statistics Canada. The national income and product accounts, often referred to simply as the national accounts, keep track of the spending of consumers, sales of producers, business investment spending, government purchases, and a variety of other flows of money between different sectors of the economy. Let’s see how they work.

The Circular-Flow Diagram, Revisited and Expanded

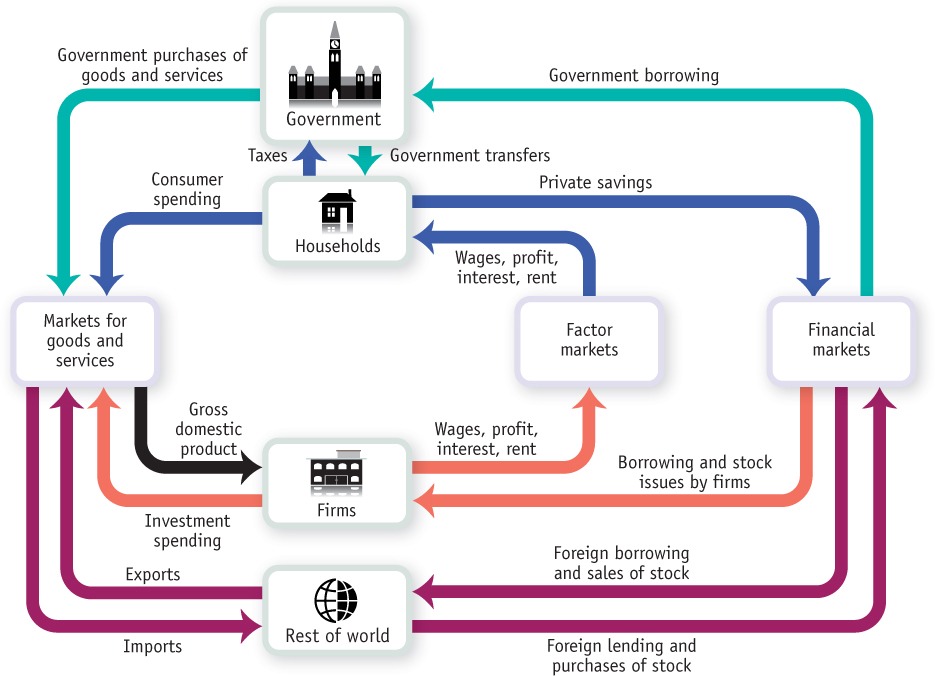

To understand the principles behind the national accounts, it helps to look at Figure 7-1, a revised and expanded circular-

Consumer spending, or consumption, is household spending on goods and services.

Figure 2-7 showed a simplified world containing only two kinds of “inhabitants,” households and firms. And it illustrated the circular flow of money between households and firms, which remains visible in Figure 7-1. In the markets for goods and services, households engage in consumer spending (or consumption), buying goods and services from domestic firms and from firms in the rest of the world. Households also own factors of production—

A stock is a share in the ownership of a company held by a shareholder.

A bond is borrowing in the form of an IOU that pays interest.

Government transfers are payments by the government to individuals for which no good or service is provided in return.

In our original, simplified circular-

Disposable income, equal to income plus government transfers minus taxes, is the total amount of household income available to spend on consumption and to save.

Private savings, equal to disposable income minus consumer spending, is disposable income that is not spent on consumption.

Second, households normally don’t spend all their disposable income on goods and services. Instead, a portion of their income is typically set aside as private savings, which goes into financial markets where individuals, banks, and other institutions buy and sell stocks and bonds as well as make loans. As Figure 7-1 shows, the financial markets also receive funds from the rest of the world and provide funds to the government, to firms, and to the rest of the world.

The banking, stock, and bond markets, which channel private savings and foreign lending into investment spending, government borrowing, and foreign borrowing, are known as the financial markets.

Before going further, we can use the box representing households to illustrate an important general feature of the circular-

Government borrowing is the total amount of funds borrowed by federal, provincial, and municipal governments in the financial markets.

Now let’s look at the other types of inhabitants we’ve added to the circular-

Government purchases of goods and services are total expenditures on goods and services by federal, provincial, and municipal governments.

The rest of the world participates in the Canadian economy in three ways:

Some of the goods and services produced in Canada are sold to residents of other countries. For example, Canada is the world’s largest exporter of durum, a type of wheat that is an important ingredient in making pasta. It is also a major exporter of other products such as canola and softwood lumber. Goods and services sold to other countries are known as exports. Export sales lead to a flow of funds from the rest of the world into Canada to pay for them.

Some of the goods and services purchased by residents of Canada are produced abroad. For example, many consumer goods are now made in China. Goods and services purchased from residents of other countries are known as imports. Import purchases lead to a flow of funds out of Canada to pay for them.

Foreigners can participate in Canadian financial markets by making trans-

actions. Foreign lending— lending by foreigners to borrowers in Canada, and purchases by foreigners of domestic assets, such as shares of stock in Canadian companies— generates a flow of funds into Canada from the rest of the world. Conversely, foreign borrowing— borrowing by foreigners from Canadian lenders and purchases by Canadians of foreign assets, such as stock in foreign companies— leads to a flow of funds out of Canada to the rest of the world.

Finally, let’s go back to the markets for goods and services. In Chapter 2 we focused only on purchases of goods and services by households. We now see that there are other types of spending on goods and services, including government purchases, investment spending by firms, imports, and exports.

Inventories are stocks of goods and raw materials held to facilitate business operations.

Notice that firms also buy goods and services in our expanded economy. For example, an automobile company that is building a new factory will buy investment goods—

Investment spending, or investment, is spending on productive physical capital—

You might ask why changes to inventories are included in investment spending—

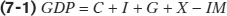

Suppose we add up consumer spending on goods and services, investment spending, government purchases of goods and services, and the value of exports, and then subtract the value of imports. This gives us a measure of the overall market value of the goods and services the economy produces. That measure has a name: it’s a country’s gross domestic product. But before we can formally define gross domestic product, or GDP, we have to examine an important distinction between classes of goods and services: the difference between final goods and services versus intermediate goods and services.

Gross Domestic Product

Final goods and services are goods and services sold to the final, or end, user.

A consumer’s purchase of a new car from a dealer is one example of a sale of final goods and services: goods and services sold to the final, or end, user. But an automobile manufacturer’s purchase of steel from a steel foundry or glass from a glassmaker is an example of purchasing intermediate goods and services: goods and services that are inputs for production of other goods and services. In the case of intermediate goods and services, the purchaser—

Intermediate goods and services are goods and services—

Gross domestic product, or GDP, is the total value of all final goods and services produced in an economy during a given period, usually a year. In 2011, the GDP in Canada was $1721 billion, or about $49 902 per person. If you are an economist trying to construct a country’s national accounts, one way to calculate GDP is to calculate it directly: survey firms and add up the total value of their production of final goods and services. We’ll explain in detail in the next section why intermediate goods, and some other types of goods as well, are not included in the calculation of GDP.

Gross domestic product, or GDP, is the total value of all final goods and services produced in the economy during a given year.

But adding up the total value of final goods and services produced isn’t the only way of calculating GDP. There is another way, based on total spending on final goods and services. Since GDP is equal to the total value of final goods and services produced in the economy, it must also equal the flow of funds received by firms from sales in the goods and services market.

Aggregate expenditure, the sum of consumer spending, investment spending, government purchases of goods and services, and exports minus imports, is the total spending on domestically produced final goods and services in the economy.

If you look again at the circular-

And there is yet a third way of calculating GDP, based on total income earned by factors of production (inputs) in the economy. Firms, and the factors of production that they employ, are owned by households. So firms must ultimately pay out what they earn to households. The flow from firms to the factor markets is the factor income paid out by firms to households in the form of wages, profit, interest, and rent. Again, by accounting rules, the value of the flow of factor income from firms to households must be equal to the flow of money into firms from the markets for goods and services. And this last value, we know, is the total value of production in the economy—

Calculating GDP

We’ve just explained that there are in fact three methods for calculating GDP:

The Value-

Added Approach: Add the total value of all final goods and services produced domestically. The Expenditure Approach: Add the spending on all domestically produced goods and services.

The Income Approach: Add the income earned by labour and capital from the domestic production of goods and services.

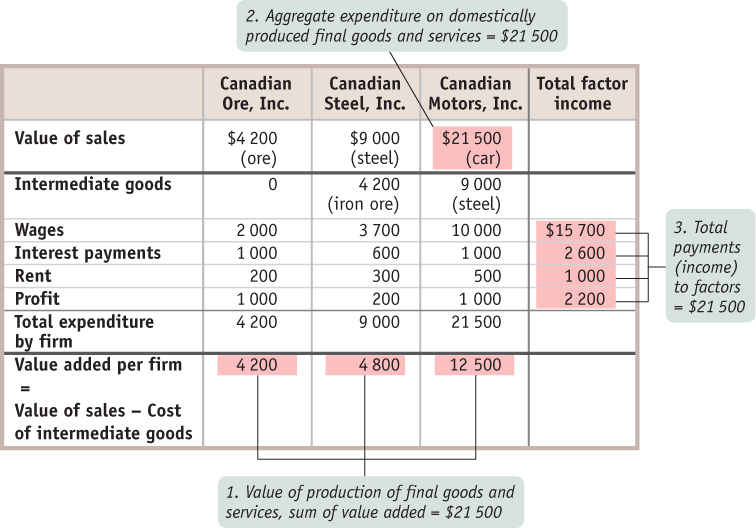

Government statisticians use all three methods. To illustrate how these three methods work, we will consider a hypothetical economy, shown in Figure 7-2. This economy consists of three firms—

The Value-

To understand why only final goods and services are included in GDP, look at the simplified economy described in Figure 7-2. Should we measure the GDP of this economy by adding up the total sales of the iron ore producer, the steel producer, and the auto producer? If we did, we would in effect be counting the value of the steel twice—

The value added of a producer is the value of its sales minus the value of its purchases of intermediate goods and services.

So counting the full value of each producer’s sales would cause us to count the same items several times and artificially inflate the calculation of GDP. For example, in Figure 7-2, the total value of all sales, intermediate and final, is $34700: $21500 from the sale of the car, plus $9000 from the sale of the steel, plus $4200 from the sale of the iron ore. Yet we know that GDP is only $21500. The way we avoid double-

That is, at each stage of the production process we subtract the cost of inputs—

In Canada, the value added of goods-

The “Our Imputed Lives” box below discusses the important assumptions the government makes to estimate the value added of households.

The Expenditure Approach: Measuring GDP as Spending on Domestically Produced Final Goods and Services Another way to calculate GDP is by adding up aggregate expenditure on domestically produced final goods and services. That is, GDP can be measured by the flow of funds into firms. Like the method that estimates GDP as the value of domestic production of final goods and services, this measurement must be carried out in a way that avoids double-

OUR IMPUTED LIVES

An old line says that when a person marries the household cook, GDP falls. And it’s true: when someone provides services for pay, those services are counted as a part of GDP. But the services family members provide to each other are not. Some economists have produced alternative measures that try to “impute” the value of household work—

GDP estimates do, however, include an imputation for the value of “owner-

If you think about it, this makes a lot of sense. In a home-

As we’ve already pointed out, the national accounts do include investment spending by firms as a part of final spending. That is, an auto company’s purchase of steel to make a car isn’t considered a part of final spending, but the company’s purchase of new machinery for its factory is considered a part of final spending. What’s the difference? Steel is an input that is used up in production; machinery will last for a number of years. Since purchases of capital goods that will last for a considerable time aren’t closely tied to current production, the national accounts consider such purchases a form of final sales.

In later chapters, we will make use of the proposition that GDP is equal to aggregate expenditure on domestically produced goods and services by final buyers. We will also develop models of how final buyers decide how much to spend. With that in mind, we’ll now examine the types of spending that make up GDP.

Look again at the markets for goods and services in Figure 7-1, and you will see that one component of sales by firms is consumer spending. Let’s denote consumer spending with the symbol C. Figure 7-1 also shows three other components of sales: sales of investment goods to other businesses, or investment spending, which we will denote by I; government purchases of goods and services, which we will denote by G; and sales to foreigners—

GDP: WHAT’S IN AND WHAT’S OUT

It’s easy to confuse what is included and what is excluded from GDP. So let’s stop here for a moment and make sure the distinction is clear. The most likely source of confusion is the difference between investment spending and spending on intermediate goods and services. Investment spending—

Why the difference? Recall from Chapter 2 that we made a distinction between resources that are used up and those that are not used up in production. An input, like steel, is used up in production. An investment good, like a metal-

Spending on changes to inventories is considered a part of investment spending, so it is also included in GDP. Why? Because, like a machine, additional inventory is an investment in future sales. And in a future period when a good is released for sale from inventories, its value is subtracted from the value of inventories and so from GDP.

Used goods are not included in GDP because, as with intermediate inputs, to include them would be to double-

Also, financial assets such as stocks and bonds are not included in GDP because they don’t represent either the production or the sale of final goods and services. Rather, a bond represents a promise to repay with interest, and a stock represents a proof of ownership. And for obvious reasons, foreign-

Since GDP includes mainly market transactions only, it usually does not include transactions that do not go through commercial markets. These transactions include household production such as homemade meals, homegrown vegetables, and some child care services; illegal transactions such as drug dealings; transactions in the underground economy such as home renovation or auto repair work that is concealed from the government, so as to avoid paying any related taxes; volunteer work; and environmental damage, such as pollution, caused by production or consumption because its value cannot be determined.

Here is a summary of what’s included and not included in GDP:

Included

Domestically produced final goods and services, including capital goods, new construction of structures, and changes to inventories

Not Included

Intermediate goods and services

Inputs, such as pre-

existing productive physical capital Used goods

Financial assets like stocks and bonds

Foreign-

produced goods and services Household production

Volunteer work

Underground economy transactions and illegal activities

Harm done to the environment during the production or consumption of goods

In reality, not all of this final spending goes toward domestically produced goods and services. We must take account of spending on imports, which we will denote by IM. Income spent on imports is income not spent on domestic goods and services—

We’ll be seeing a lot of Equation 7-1 in later chapters.

Factor incomes are incomes earned by factors of production, which include wages, interest, rent dividends, and profits.

The Income Approach: Measuring GDP as Income Earned from Production of Goods and Services A final way to calculate GDP is to add two sources of income: factor incomes and non-

Non-factor payments are the difference between the prices paid for final goods and services and the amount received by factors of production, which include net indirect taxes and capital depreciation.

Non-factor payments consist of the income earned by the federal government as a result of the production of goods and services. They are the difference between the prices for which final products are sold in the market and the amount actually received (and kept) by the factors of production before income taxes are removed. One example is net indirect taxes, which are indirect taxes, such as provincial and federal sales taxes, less any subsidies paid to purchasers. Another example is capital depreciation, which is the removal of productive physical capital from the capital stock as it wears out or becomes obsolete; such depreciation can be claimed as an income tax deduction.

Figure 7-2 shows how this calculation works for our simplified economy. The shaded column at the far right shows the total wages, interest, and rent paid by all these firms as well as their total profit. Summing up all of these yields total factor income of $21500—again, equal to GDP.

Here, we’ll focus on the expenditure approach and the income approach in calculating GDP. It’s important to keep in mind, however, that all the money spent on domestically produced goods and services generates income for someone in the economy because one person’s spending is another person’s income—

The Components of GDP Now that we know how GDP is calculated in principle, let’s see what it looks like in practice.

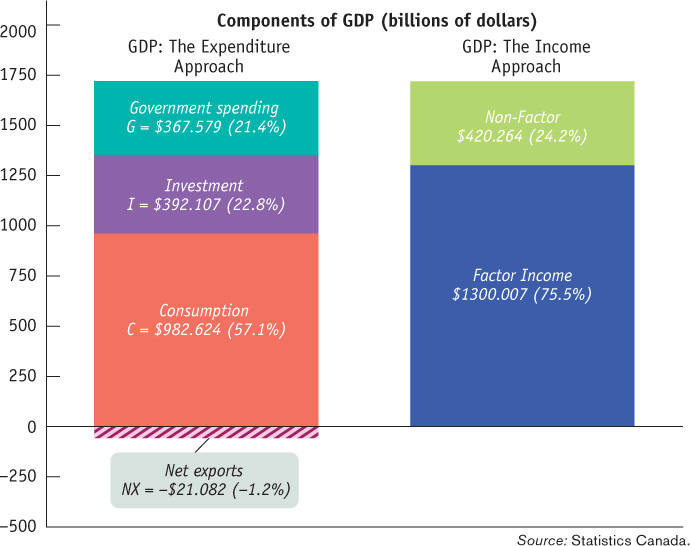

Figure 7-3 shows the last two methods of calculating GDP side by side. The height of each bar above the horizontal axis represents the GDP of the Canadian economy in 2011: $1721 billion. Each bar is divided to show the breakdown of that total in terms of where the value was added, how the money was spent, and where the income was generated.

Net exports are the difference between the value of exports and the value of imports.

The left bar in Figure 7-3 corresponds to the second method of calculating GDP, showing the breakdown by the four types of aggregate expenditure. The total length of the bar on the left is longer than the bar on the right, a difference of $21 billion (which, as you can see, is the amount by which the left bar extends below the horizontal axis). That’s because the total length of the left bar represents total spending in the economy, spending on both domestically produced and foreign-

The bar on the right shows Canada’s GDP calculated according to the income approach. About 76% of Canada’s GDP in 2011, or about $1300 billion, consisted of factor incomes. Of that amount, the labour force earned $889.5 billion, the firms’ owners made $366.7 billion, and the owners of capital made $73.8 billion. The remainder of the 2011 GDP, about 24%, or $420.3 billion, comprised non-

MORE ON NATIONAL INCOME

What is GNP? This term refers to the total factor income earned by residents of a country. It excludes the factor income earned by foreigners, like profits paid to foreign investors who own Canadian stocks and payments to foreigners who work temporarily in Canada. It includes the factor income earned abroad by Canadians, like the profits of the European operations of Blackberry that accrue to Blackberry’s Canadian shareholders, and the wages of Canadians who work abroad temporarily. The relationship between GDP and GNP is: GNP = GDP + (factor income earned abroad by Canadians − factor income earned by foreigners in Canada).

In 2011, Canadian GDP was about 1.9% higher than its GNP, mainly because of foreign companies operating in Canada.

Statistics Canada releases Canada’s national income data monthly. But occasionally Statistics Canada will revise these data months afterward. Why? It is because whenever Statistics Canada releases data, there is a trade-

What GDP Tells Us

Now we’ve seen the various ways that gross domestic product is calculated. But what does the measurement of GDP tell us?

The most important use of GDP is as a measure of the size of the economy, providing us a scale against which to measure the economic performance of other years or to compare the economic performance of other countries. For example, suppose you want to compare the economies of different nations. A natural approach is to compare their GDPs. In 2011, as we’ve seen, Canada’s GDP was quite large: $1721 billion. But China’s GDP was $7126 billion, the U.S. had the biggest national economy at $14 928 billion, and the European Union’s GDP was $16 488 billion. (All figures in Canadian dollars.) This comparison tells us that China, although it has the world’s second-

Still, one must be careful when using GDP numbers, especially when making comparisons over time. That’s because part of the increase in the value of GDP over time represents increases in the prices of goods and services rather than an increase in output. For example, from 1992 to 2011, Canada’s GDP increased in size about 2.5 times, from $700 billion to $1721 billion. But the Canadian economy did not really increase by 2.5 times over that period. To measure actual changes in aggregate output, we need a modified version of GDP that is adjusted for price changes, known as real GDP. We’ll see next how real GDP is calculated.

CREATING THE NATIONAL ACCOUNTS

The national accounts, like modern macroeconomics, owe their creation to the Great Depression. Before the Depression, many countries had collected some limited data regarding their economic activities. For example, Canada released its first publication dealing with output for selected industries in 1926. Likewise, U.S. government agencies had collected data on that country’s economic activities for years. But when the Depression arrived in the 1930s, this information was far from complete; nor was there any systematic way to combine and interpret it. Consequently, as the U.S. economy plunged ever lower during the Depression, lack of adequate economic theories and lack of information hampered American policy-

To solve this problem, in 1937, the U.S. Department of Commerce commissioned economist Simon Kuznets to develop a set of national income accounts so there would be a proper, systematic way to collect data on economic activities. Accordingly, Kuznets presented the first version of these accounts to the U.S. Congress in 1937 and in a research report titled National Income, 1929–35.

This report lead to the development of national income accounting in the U.S., a policy that has proven so beneficial for economic analysis and policy-

Since then, Statistics Canada1 has collected and published data related to our national accounts regularly. Nowadays, these detailed statistics are given in Canada’s System of National Accounts (CSNA), which Statistics Canada describes as “a set of statistical statements, or accounts, each one providing an aggregated portrait of economic activity during a given period.”2 The data used to compile the national accounts are taken from many sources including customs records, income tax returns, government public accounts, surveys conducted by government agencies, statistics collected by departments at all levels of governments, and so on. Once the data are collected, compiled, and tabulated, they are integrated into the CSNA framework for analysis. These data are used extensively. For example, the federal government and the Bank of Canada use them to formulate policies and to assess the country’s economic performance. The federal government also uses the data to set the payments it makes to each province under the equalization plan. Under this plan, the federal government makes payments to less wealthy, or “have-

The CSNA includes numerous related items, such as the Monthly Retail Trade Survey (MRTS). Retail sales are an important component of gross domestic product, which is a key indicator of consumer purchasing patterns in Canada. This information is valuable to many organizations. Federal and provincial governments use it to gain an understanding of the overall economy and to design tax and spending policies. The Bank of Canada uses it to decide on monetary policy. For example, high retail sales could suggest to the federal government that its economic stimulus programs have been successful and could suggest to the Bank of Canada that it should consider raising interest rates. A business can use this information to compare its own sales performance against the industry standard. Investors may use it to decide whether to invest in a certain industry or not.

Quick Review

A country’s national income and product accounts, or national accounts, track flows of money among economic sectors.

Factor incomes are incomes earned by factors of production, which include wages, interest, rent dividends, and profits. Non-factor payments are the difference between the prices paid for final goods and services and the amount received by factors of production, which include net indirect taxes and capital depreciation.

Households receive factor income in the form of wages, profit from ownership of stocks, interest paid on bonds, and rent. They also receive government transfers.

Households allocate disposable income between consumer spending and private savings—funds that flow into the financial markets, financing investment spending and any government borrowing.

Government purchases of goods and services are total expenditures by all levels of government on goods and services.

Gross domestic product, or GDP, can be calculated in three different ways: add up the value added by all firms; add up all spending on domestically produced final goods and services, an amount equal to aggregate expenditure; or add up income earned from production of goods and services. Intermediate goods and services are not included in the calculation of GDP, while changes in inventories and net exports are.

Check Your Understanding 7-1

CHECK YOUR UNDERSTANDING 7-1

Explain why the three methods of calculating GDP produce the same estimate of GDP.

Let’s start by considering the relationship between the total value added of all domestically produced final goods and services and aggregate spending on domestically produced final goods and services. These two quantities are equal because every final good and service produced in the economy is either purchased by someone or added to inventories. And additions to inventories are counted as spending by firms. Next, consider the relationship between aggregate spending on domestically produced final goods and services and total factor income. These two quantities are equal because all spending that is channelled to firms to pay for purchases of domestically produced final goods and services is revenue for firms. Those revenues must be paid out by firms to their factors of production in the form of wages, profit, interest, and rent. Taken together, this means that all three methods of calculating GDP are equivalent.

What are the various sectors to which firms make sales? What are the various ways in which households are linked with other sectors of the economy?

Firms make sales to other firms, households, the government, and the rest of the world. Households are linked to firms through the sale of factors of production to firms, through purchases from firms of final goods and services, and through lending funds to firms in the financial markets. Households are linked to the government through their payment of taxes, their receipt of transfers, and their lending of funds to the government via the financial markets. Finally, households are linked to the rest of the world through their purchases of imports and transactions with foreigners in financial markets.

Consider Figure 7-2 and suppose you mistakenly believed that total value added was $30500, the sum of the sales price of a car and a car’s worth of steel. What items would you be counting twice?

You would be counting the value of the steel twice—