9.4 Success, Disappointment, and Failure

As we’ve seen, rates of long-

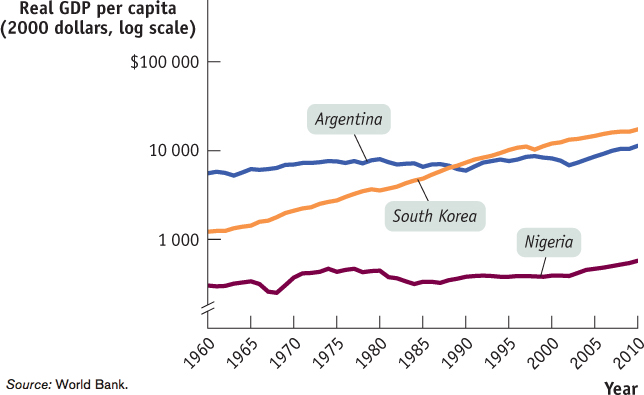

Figure 9-11 shows trends since 1960 in real GDP per capita in 2000 dollars for three countries: Argentina, Nigeria, and South Korea. (As in Figure 9-1, the vertical axis is drawn in logarithmic scale.) We have chosen these countries because each is a particularly striking example of what has happened in its region. South Korea’s amazing rise is part of a broad “economic miracle” in East Asia. Argentina’s slow progress, interrupted by repeated setbacks, is more or less typical of the disappointing growth that has characterized Latin America. And Nigeria’s unhappy story until very recently—

Source: World Bank.

East Asia’s Miracle

In 1960 South Korea was a very poor country. In fact, in 1960 its real GDP per capita was lower than that of India today. But, as you can see from Figure 9-11, beginning in the early 1960s South Korea began an extremely rapid economic ascent: real GDP per capita grew about 7% per year for more than 30 years. Today South Korea, though still somewhat poorer than Canada or the United States, looks very much like an economically advanced country.

South Korea’s economic growth is unprecedented in history: it took the country only 35 years to achieve growth that required centuries elsewhere. Yet South Korea is only part of a broader phenomenon, often referred to as the East Asian economic miracle. High growth rates first appeared in South Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Singapore but then spread across the region, most notably to China. Since 1975, the whole region has increased real GDP per capita by 6% per year, more than three times Canada’s historical rate of growth.

How have the Asian countries achieved such high growth rates? The answer is that all of the sources of productivity growth have been firing on all cylinders. Very high savings rates, the percentage of GDP that is saved nationally in any given year, have allowed the countries to significantly increase the amount of physical capital per worker. Very good basic education has permitted a rapid improvement in human capital. And these countries have experienced substantial technological progress.

Why didn’t any economy achieve this kind of growth in the past? Most economic analysts think that East Asia’s growth spurt was possible because of its relative backwardness. That is, by the time that East Asian economies began to move into the modern world, they could benefit from adopting the technological advances that had been generated in technologically advanced countries such as Canada.

In 1900, Canada could not have moved quickly to a modern level of productivity because much of the technology that powers the modern economy, from jet planes to computers, hadn’t been invented yet. In 1970, South Korea probably still had lower productivity than Canada had in 1900, but it could rapidly upgrade its productivity by adopting technology that had been developed in Canada, the United States, Europe, and Japan over the previous century. This was aided by a huge investment in human capital through widespread schooling.

According to the convergence hypothesis, international differences in real GDP per capita tend to narrow over time.

The East Asian experience demonstrates that economic growth can be especially fast in countries that are playing catch-

Even before we get to that evidence, however, we can say right away that starting with a relatively low level of real GDP per capita is no guarantee of rapid growth, as the examples of Latin America and Africa both demonstrate.

Latin America’s Disappointment

In 1900, Latin America was not considered an economically backward region. Natural resources, including both minerals and cultivatable land, were abundant. Some countries, notably Argentina, attracted millions of immigrants from Europe in search of a better life. Measures of real GDP per capita in Argentina, Uruguay, and southern Brazil were comparable to those in economically advanced countries.

Since about 1920, however, growth in Latin America has been disappointing. As Figure 9-11 shows in the case of Argentina, growth has been disappointing for many decades, until 2000 when it finally began to increase. The fact that South Korea is now much richer than Argentina would have seemed inconceivable a few generations ago.

Why did Latin America stagnate? Comparisons with East Asian success stories suggest several factors. The rates of savings and investment spending in Latin America have been much lower than in East Asia, partly as a result of irresponsible government policy that has eroded savings through high inflation, bank failures, and other disruptions. Education—

In the 1980s, many economists came to believe that Latin America was suffering from excessive government intervention in markets. They recommended opening the economies to imports, selling off government-

Africa’s Troubles and Promise

Africa south of the Sahara is home to about 780 million people, more than 22 times the population of Canada. On average, they are very poor, nowhere close to Canada’s living standards 100 or even 200 years ago. And economic progress has been both slow and uneven, as the example of Nigeria, the most populous nation in the region, suggests. In fact, real GDP per capita in sub-

This is a very disheartening story. What explains it?

Several factors are probably crucial. Perhaps first and foremost is the problem of political instability. In the years since 1975, large parts of Africa have experienced savage civil wars (often with outside powers backing rival sides) that have killed millions of people and made productive investment spending impossible. The threat of war and general anarchy has also inhibited other important preconditions for growth, such as education and provision of necessary infrastructure.

Property rights are also a major problem. The lack of legal safeguards means that property owners are often subject to extortion because of government corruption, making them averse to owning property or improving it. This is especially damaging in a country that is very poor.

While many economists see political instability and government corruption as the leading causes of underdevelopment in Africa, some—

Sachs, along with economists from the World Health Organization, has highlighted the importance of health problems in Africa. In poor countries, worker productivity is often severely hampered by malnutrition and disease. In particular, tropical diseases such as malaria can only be controlled with an effective public health infrastructure, something that is lacking in much of Africa. At the time of writing, economists are studying certain regions of Africa to determine whether modest amounts of aid given directly to residents for the purposes of increasing crop yields, reducing malaria, and increasing school attendance can produce self-

Although the example of African countries represents a warning that long-

ARE ECONOMIES CONVERGING?

In the 1950s, the United States was the richest country in the world: much of Europe and Canada seemed quaint and backward to American visitors, and Japan seemed very poor. Today, Toronto, Paris, and Tokyo look like cities as rich as New York. Although Americans still enjoy a higher level of real GDP per capita, the differences in the standards of living among the United States, Canada, Europe, and Japan are relatively small.

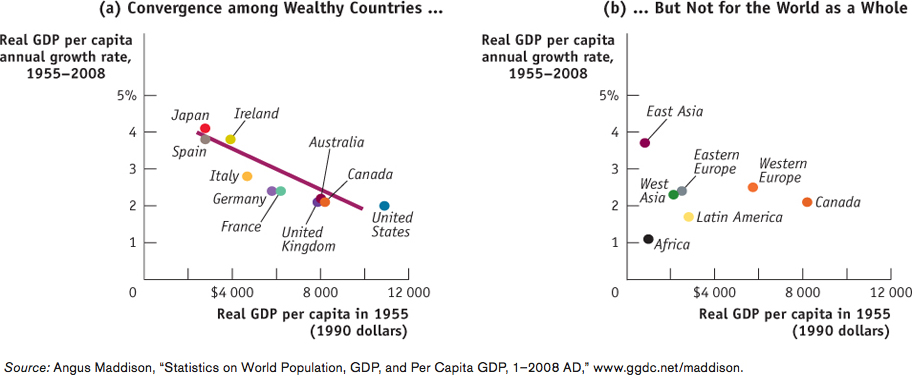

Many economists have argued that this convergence in living standards is normal; the convergence hypothesis says that relatively poor countries should have higher rates of growth of real GDP per capita than relatively rich countries. And if we look at today’s relatively well-

Source: Angus Maddison, “Statistics on World Population, GDP, and Per Capita GDP, 1–2008 AD,” www.ggdc.net/

But economists who looked at similar data realized that these results depend on the countries selected. If you look at successful economies that have a high standard of living today, you find that real GDP per capita has converged. But looking across the world as a whole, including countries that remain poor, there is little evidence of convergence. Figure 9-12b illustrates this point using data for regions rather than individual countries (other than Canada). In 1955, East Asia and Africa were both very poor regions. Over the next 53 years, the East Asian regional economy grew quickly, as the convergence hypothesis would have predicted, but the African regional economy grew very slowly. In 1955, Western Europe had substantially higher real GDP per capita than Latin America. But, contrary to the convergence hypothesis, the Western European regional economy grew more quickly over the next 53 years, widening the gap between the regions.

So is the convergence hypothesis all wrong? No: economists still believe that countries with relatively low real GDP per capita tend to have higher rates of growth than countries with relatively high real GDP per capita, other things equal. But other things—

Because other factors differ, such as protection of property rights and political stability, however, there is no clear tendency toward convergence in the world economy as a whole. Western Europe, North America, and parts of Asia are becoming more similar in real GDP per capita, but the gap between these regions and the rest of the world is growing.

Quick Review

East Asia’s spectacular growth was generated by high savings and investment spending rates, emphasis on education, and adoption of technological advances from other countries.

Poor education, political instability, and irresponsible government policies are major factors in the slow growth of Latin America.

In sub-

Saharan Africa, severe instability, war, and poor infrastructure— particularly affecting public health— resulted in a catastrophic failure of growth. But economic performance in recent years has been much better than in preceding years. The convergence hypothesis seems to hold only when other things that affect economic growth—

such as education, infrastructure, property rights, and so on— are held equal.

Check Your Understanding 9-4

CHECK YOUR UNDERSTANDING 9-4

Some economists think the high rates of growth of productivity achieved by many Asian economies cannot be sustained. Why might they be right? What would have to happen for them to be wrong?

The conditional version of the convergence hypothesis says that countries grow faster, other things equal, when they start from relatively low GDP per capita. From this we can infer that they grow more slowly, other things equal, when their real GDP per capita is relatively higher. This points to lower future Asian growth. However, other things might not be equal: if Asian economies continue investing in human capital, if savings rates continue to be high, if governments invest in infrastructure, and so on, growth might continue at an accelerated pace.

Consider Figure 9-12b. Based on the data there, which regions support the convergence hypothesis? Which do not? Explain.

The regions of East Asia, Western Europe, Canada, and the United States support the convergence hypothesis because a comparison among them shows that the growth rate of real GDP per capita falls as real GDP per capita rises. Eastern Europe, West Asia, Latin America, and Africa do not support the hypothesis because they all have much lower real GDP per capita than the United States but have either approximately the same growth rate (West Asia and Eastern Europe) or a lower growth rate (Africa and Latin America).

Some economists think the best way to help African countries is for wealthier countries to provide more funds for basic infrastructure. Others think this policy will have no long-

run effect unless African countries have the financial and political means to maintain this infrastructure. What policies would you suggest?

The evidence suggests that both sets of factors matter: better infrastructure is important for growth, but so is political and financial stability. Policies should try to address both areas.