Deflation

Before World War II, deflation—a falling aggregate price level—

Why is deflation a problem? And why is it hard to end?

Debt Deflation

Deflation, like inflation, produces both winners and losers—

In a famous analysis at the beginning of the Great Depression, Irving Fisher (who first analyzed the Fisher effect of expected inflation on interest rates, described in Chapter 25) claimed that the effects of deflation on borrowers and lenders can worsen an economic slump. Deflation, in effect, takes real resources away from borrowers and redistributes them to lenders.

Debt deflation is the reduction in aggregate demand arising from the increase in the real burden of outstanding debt caused by deflation.

Fisher argued that borrowers, who lose from deflation, are typically short of cash and will be forced to cut their spending sharply when their debt burden rises. Lenders, however, are unlikely to increase spending sharply when the values of the loans they own rise. The overall effect, said Fisher, is that deflation reduces aggregate demand, deepening an economic slump, which, in a vicious circle, may lead to further deflation. The effect of deflation in reducing aggregate demand, known as debt deflation, probably played a significant role in the Great Depression.

Effects of Expected Deflation

Like expected inflation, expected deflation affects the nominal interest rate. Look back at Figure 25-7, which demonstrated how expected inflation affects the equilibrium interest rate. In Figure 25-7, the equilibrium nominal interest rate is 4% if the expected inflation rate is 0%. Clearly, if the expected inflation rate is −3%—if the public expects deflation at 3% per year—

There is a zero bound on the nominal interest rate: it cannot go below zero.

But what would happen if the expected rate of inflation is −5%? Would the nominal interest rate fall to −1%, in which lenders are paying borrowers 1% on their debt? No. Nobody would lend money at a negative nominal rate of interest, because they could do better by simply holding cash. This illustrates what economists call the zero bound on the nominal interest rate: it cannot go below zero.

This zero bound can limit the effectiveness of monetary policy. Suppose the economy is depressed, with output below potential output and the unemployment rate above the natural rate. Normally the central bank can respond by cutting interest rates so as to increase aggregate demand. If the nominal interest rate is already zero, however, the central bank cannot push it down any further. Banks refuse to lend and consumers and firms refuse to spend because, with a negative inflation rate and a 0% nominal interest rate, holding cash yields a positive real return: with falling prices, a given amount of cash buys more over time. Any further increases in the monetary base will either be held in bank vaults or held as cash by individuals and firms, without being spent.

The economy is in a liquidity trap when conventional monetary policy is ineffective, because nominal interest rates are up against the zero bound.

A situation in which conventional monetary policy to fight a slump—

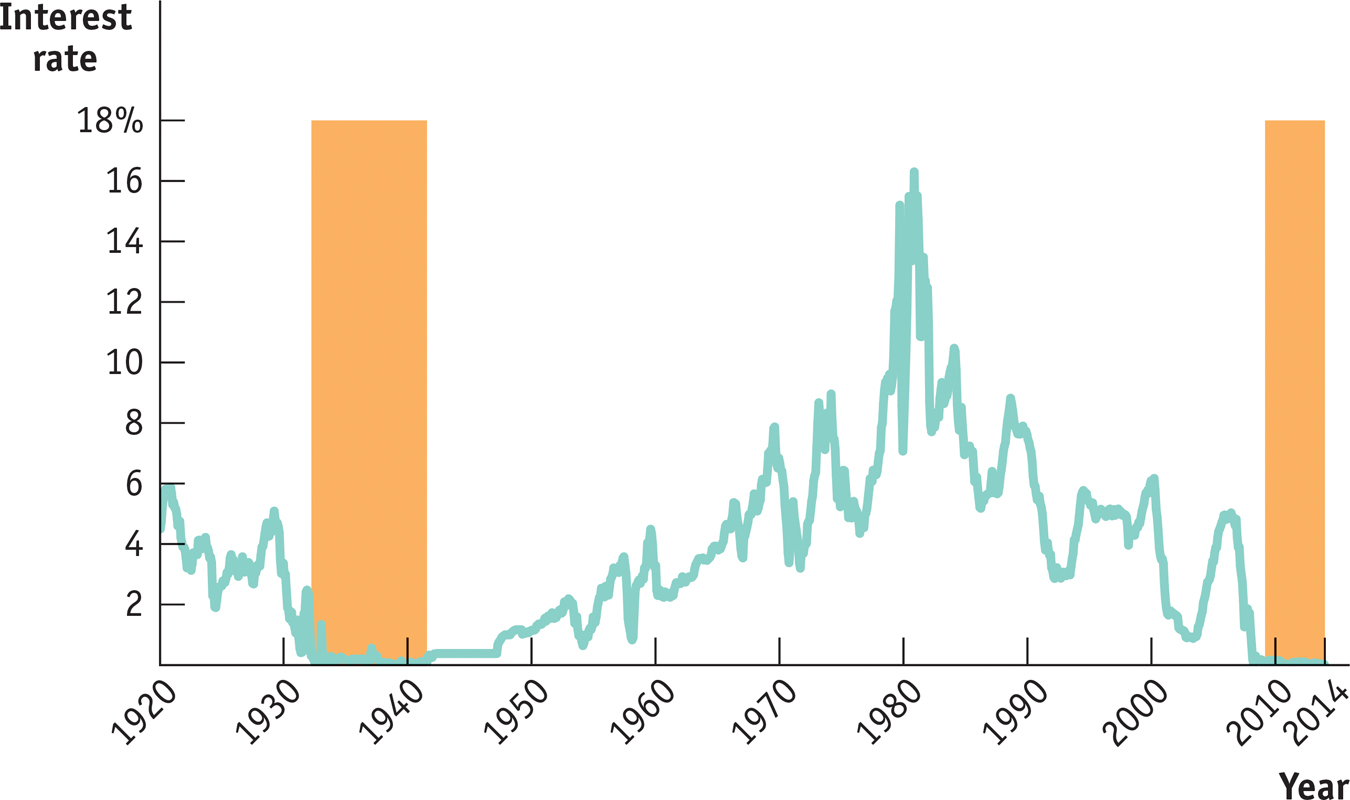

31-14

The Zero Bound in U.S. History

However, the recent history of the Japanese economy, shown in Figure 31-15, provides a modern illustration of the problem of deflation and the liquidity trap. Japan experienced a huge boom in the prices of both stocks and real estate in the late 1980s, then saw both bubbles burst. The result was a prolonged period of economic stagnation, the so-

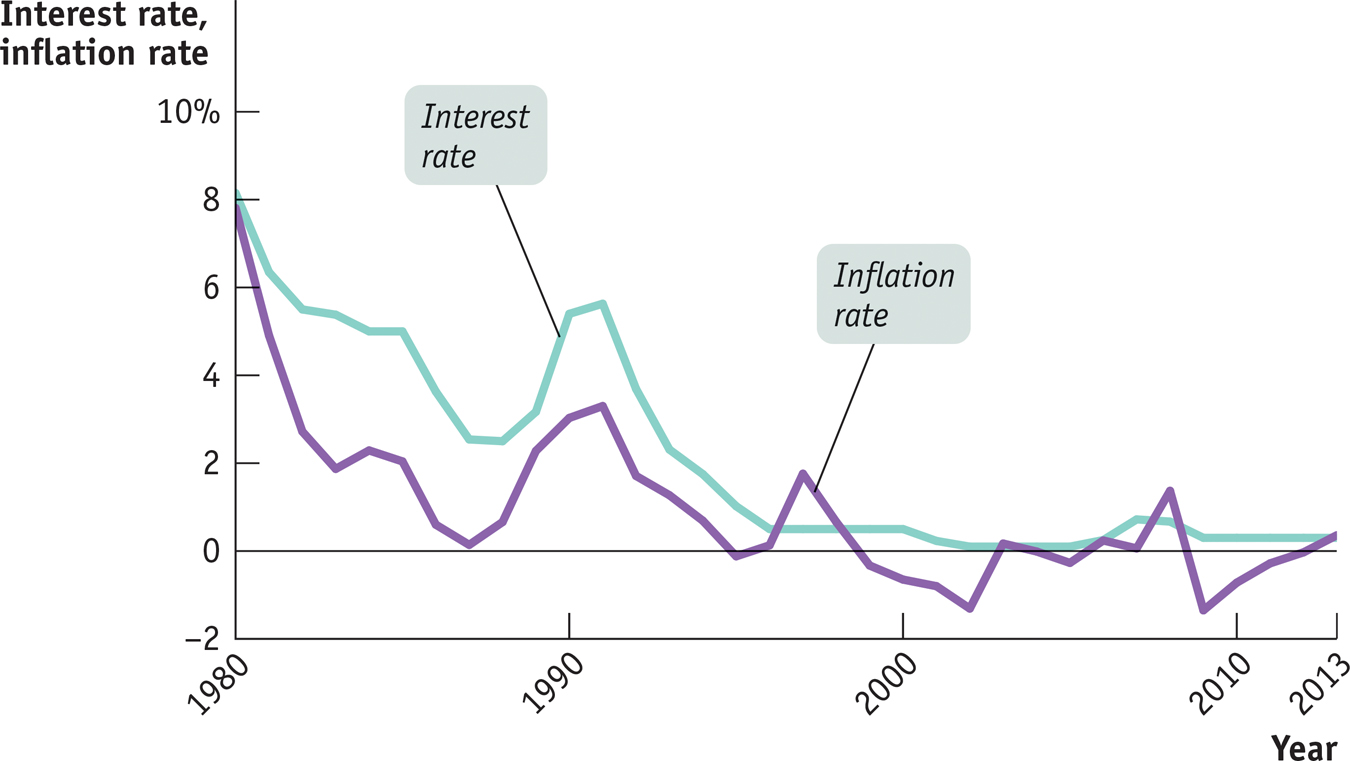

31-15

Japan’s Lost Decades

In an effort to fight the weakness of the economy, the Bank of Japan—

In the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, the world’s most important central banks—

!worldview! ECONOMICS in Action: Is Europe Turning Japanese?

Is Europe Turning Japanese?

In the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, officials at the Federal Reserve were deeply worried about the possibility of “Japanification”—that is, they worried that, like Japan since the 1990s, the United States might find itself stuck in a deflationary trap. To avoid this possibility, they took some extraordinary measures, notably the large-

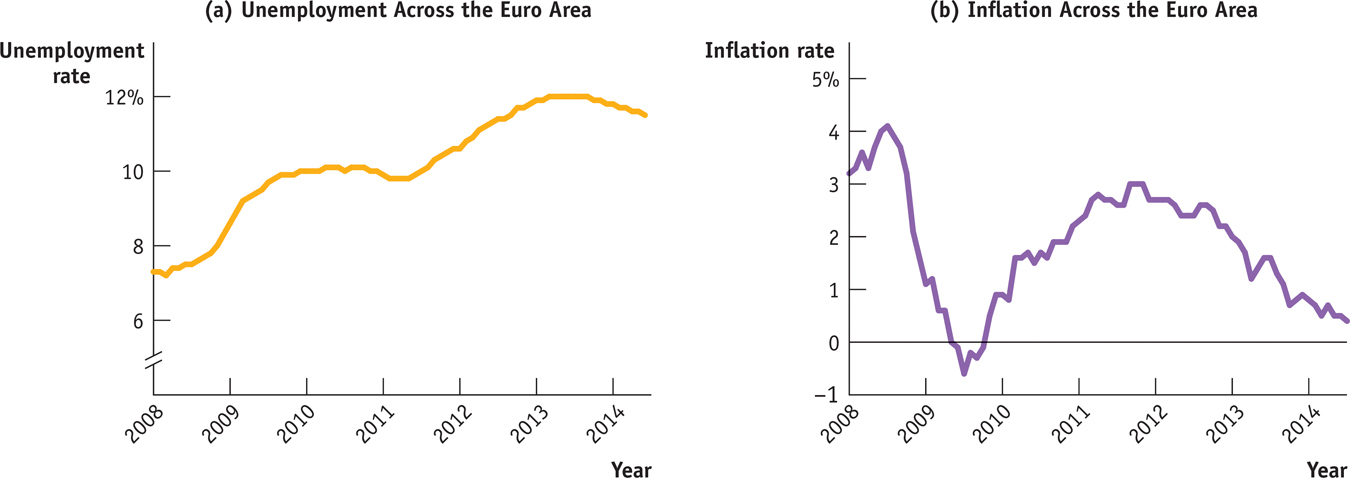

31-16

Trouble in Europe, 2008–

But Europe was a different story. Where the U.S. recovery from the recession of 2007–

And like the Bank of Japan a number of years earlier, the European Central Bank was finding it hard to devise an effective answer to the slide toward deflation. In June 2014, it took the extraordinary step of reducing one of its key policy, rates, the interest rate it pays on deposits of private banks, to minus 0.1 percent—

Quick Review

Unexpected deflation helps lenders and hurts borrowers. This can lead to debt deflation, which has a contractionary effect on aggregate demand.

Deflation makes it more likely that interest rates will end up against the zero bound. When this happens, the economy is in a liquidity trap, and monetary policy is ineffective.

31-4

Question 16.8

Why won’t anyone lend money at a negative nominal rate of interest? How can this pose problems for monetary policy?

If the nominal interest rate is negative, an individual is better off simply holding cash, which has a 0% nominal rate of return. If the options facing an individual are to lend and receive a negative nominal interest rate or to hold cash and receive a 0% nominal interest rate, the individual will hold cash. Such a scenario creates the possibility of a liquidity trap, in which monetary policy is ineffective because the nominal interest rate cannot fall below zero. Once the nominal interest rate falls to zero, further increases in the money supply will lead firms and individuals to simply hold the additional cash.

Solution appears at back of book.

Licenses to Print Money

People sometimes talk about profitable companies as having a “license to print money.” Well, the British firm De La Rue actually does. In 1930, De La Rue, printer of items such as postage stamps, expanded into the money-

De La Rue’s business received some unexpected attention in 2011 when Muammar Gaddafi, the dictator who had ruled Libya from 1969 until 2011, was fighting to suppress a fierce popular uprising. To finance his efforts, he turned to seignorage, ordering around $1.5 billion worth of Libyan dinars printed. But Libyan banknotes weren’t printed in Libya; they were printed in Britain at one of De La Rue’s facilities. The British government, an enemy of the Gaddafi regime, seized the new banknotes before they could be flown to Libya, refusing to release them until Gaddafi had been overthrown.

Why do so many countries turn to private companies like De La Rue and its main rivals, the German firm Giesecke & Devrient and the French firm Oberthur, to print their currencies? The short answer is that printing money isn’t as easy as it sounds—

Actually, De La Rue has had its own problems with quality control: a scandal erupted in 2010, when it emerged that one of its plants had been producing defective security paper and that employees had covered up the problems. Nonetheless, many countries will surely continue relying on expert private firms to produce their currencies.

QUESTIONS FOR THOUGHT

Question 16.9

How can a government obtain revenue by printing money when someone else actually prints the money?

How can a government obtain revenue by printing money when someone else actually prints the money?Question 16.10

Why, exactly, would Gaddafi have resorted to the printing press in early 2011?

Why, exactly, would Gaddafi have resorted to the printing press in early 2011?Question 16.11

Were there risks to the Libyan economy in releasing those dinars to the new government?

Were there risks to the Libyan economy in releasing those dinars to the new government?