1.3 15Taxes

WHAT YOU WILL LEARN

The effects of taxes on supply and demand

The effects of taxes on supply and demand

How taxes affect total surplus and can create deadweight loss

How taxes affect total surplus and can create deadweight loss

Taxes are necessary: all governments need money to function. Without taxes, governments could not provide the services we want, from national defense to public parks. But taxes have a cost that normally exceeds the money actually paid to the government. That’s because taxes distort incentives to engage in mutually beneficial transactions.

Making tax policy isn’t easy—

One principle used for guiding tax policy is efficiency: taxes should be designed to distort incentives as little as possible. But efficiency is not the only concern when designing tax rates. It’s also important that a tax be seen as fair. Tax policy always involves striking a balance between the pursuit of efficiency and the pursuit of perceived fairness.

In this module, we will look at how taxes affect efficiency and fairness.

Equity, Efficiency, and Taxes

It’s easy to get carried away with the idea that markets are always good and that economic policies that interfere with efficiency are bad. But that would be misguided because there is another factor to consider: society cares about equity, or what’s “fair.” There is often a trade-

In fact, the debate about equity and efficiency is at the core of most debates about taxation. Proponents of taxes that redistribute income from the rich to the poor often argue for the fairness of such redistributive taxes. Opponents of taxation often argue that phasing out certain taxes would make the economy more efficient.

A progressive tax rises more than in proportion to income.

A regressive tax rises less than in proportion to income.

A proportional tax rises in proportion to income.

Because taxes are ultimately paid out of income, economists classify taxes according to how they vary with the income of individuals. A tax that rises more than in proportion to income, so that high-

The Effects of Taxes on Total Surplus

An excise tax is a tax on sales of a particular good or service.

To understand the economics of taxes, it’s helpful to look at a simple type of tax known as an excise tax—a tax charged on each unit of a good or service that is sold. Most tax revenue in the United States comes from other kinds of taxes, but excise taxes are common. For example, there are excise taxes on gasoline, cigarettes, and foreign-

The Effect of an Excise Tax on Quantities and Prices

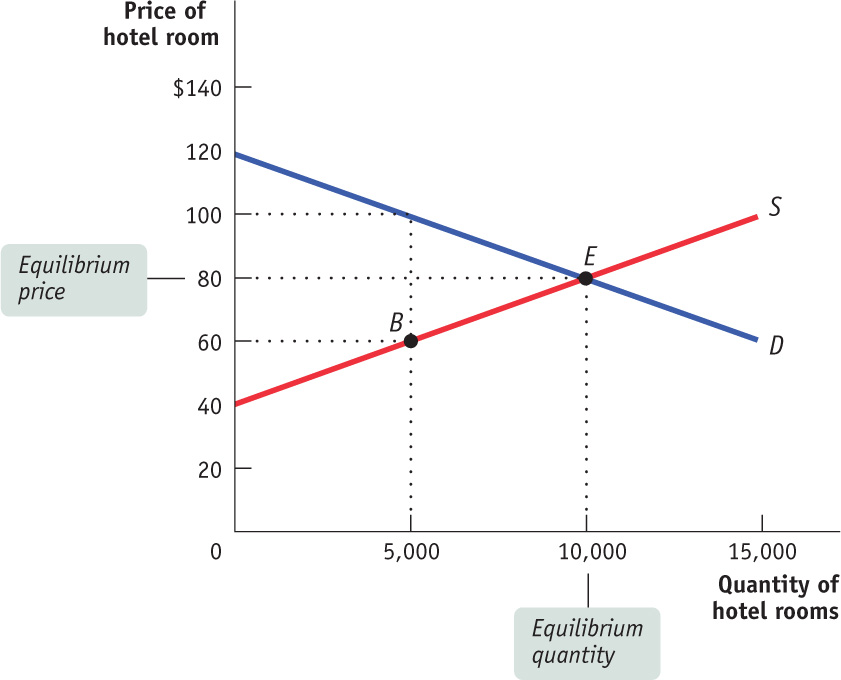

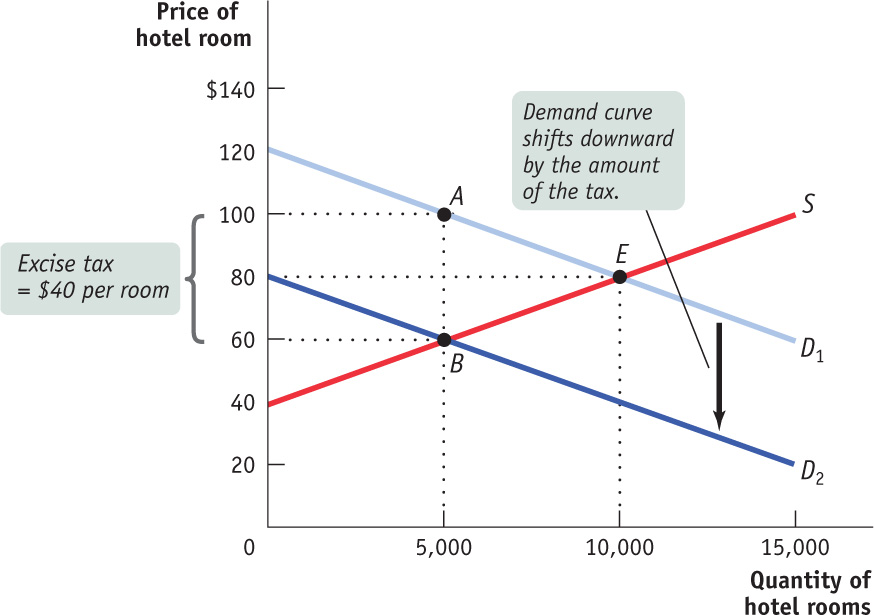

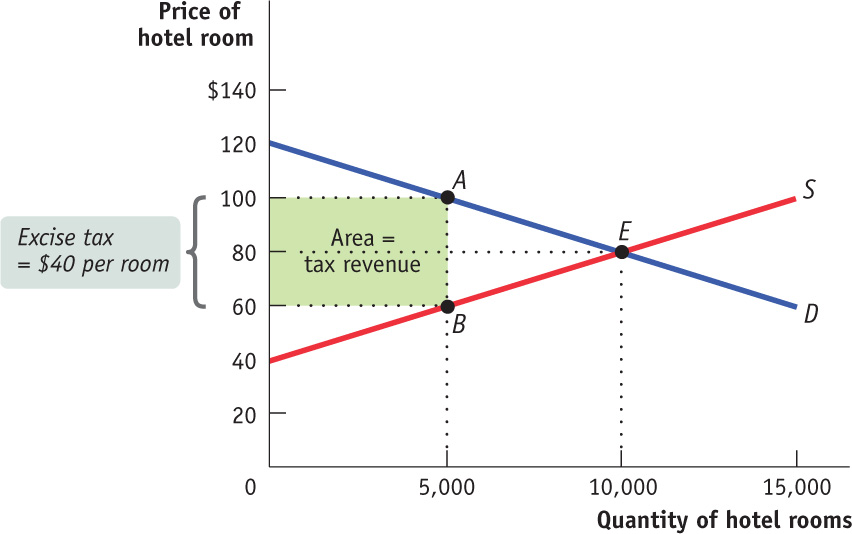

Suppose that the supply and demand for hotel rooms in the city of Potterville are as shown in Figure 15-1. We’ll make the simplifying assumption that all hotel rooms are the same. In the absence of taxes, the equilibrium price of a room is $80 per night and the equilibrium quantity of hotel rooms rented is 10,000 per night.

FIGURE15-1The Supply and Demand for Hotel Rooms in Potterville

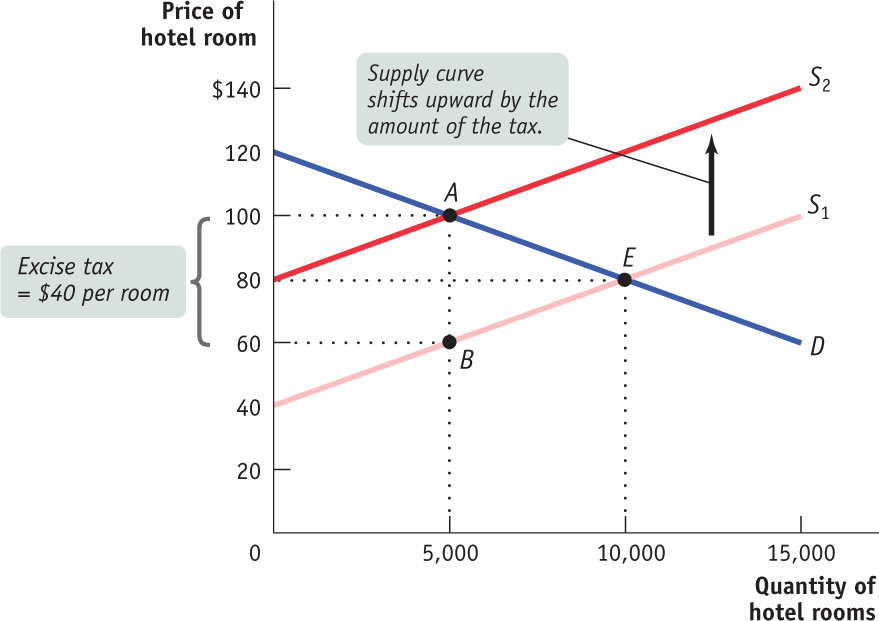

Now suppose that Potterville’s government imposes an excise tax of $40 per night on hotel rooms—

What does this imply about the supply curve for hotel rooms in Potterville? To answer this question, we must compare the incentives of hotel owners pre-

From Figure 15-1 we know that pre-

The upward shift of the supply curve caused by the tax is shown in Figure 15-2, where S1 is the pre-

FIGURE15-2An Excise Tax Imposed on Hotel Owners

Let’s check this again. How do we know that 5,000 rooms will be supplied at a price of $100? Because the price net of tax is $60, and according to the original supply curve, 5,000 rooms will be supplied at a price of $60, as shown by point B in Figure 15-2.

An excise tax drives a wedge between the price paid by consumers and the price received by producers. As a result of this wedge, consumers pay more and producers receive less.

In our example, consumers—

Like a quota on sales, discussed in Module 14, this tax leads to inefficiency by distorting incentives and creating missed opportunities for mutually beneficial transactions.

It’s important to recognize that as we’ve described it, Potterville’s hotel tax is a tax on the hotel owners, not their guests—

What would happen if the city levied a tax on consumers instead of producers? That is, suppose that instead of requiring hotel owners to pay $40 a night for each room they rent, the city required hotel guests to pay $40 for each night they stayed in a hotel. The answer is shown in Figure 15-3. If a hotel guest must pay a tax of $40 per night, then the price for a room paid by that guest must be reduced by $40 in order for the quantity of hotel rooms demanded post-

FIGURE15-3An Excise Tax Imposed on Hotel Guests

At every quantity demanded, the demand price—

If you compare Figures 15-2 and 15-3, you will notice that the effects of the tax are the same even though different curves are shifted. In each case, consumers pay $100 per unit (including the tax, if it is their responsibility), producers receive $60 per unit (after paying the tax, if it is their responsibility), and 5,000 hotel rooms are bought and sold. In fact, it doesn’t matter who officially pays the tax—

Tax incidence is the distribution of the tax burden.

This example illustrates a general principle of tax incidence, a measure of who really pays a tax: the burden of a tax cannot be determined by looking at who writes the check to the government. In this particular case, a $40 tax on hotel rooms brings about a $20 increase in the price paid by consumers and a $20 decrease in the price received by producers. Regardless of whether the tax is levied on consumers or producers, the incidence of the tax is the same. As we will see next, the burden of a tax depends on the price elasticities of supply and demand.

Price Elasticities and Tax Incidence

We’ve just learned that the incidence of an excise tax doesn’t depend on who officially pays it. In the example shown in Figures 15-

What determines how the burden of an excise tax is allocated between consumers and producers? The answer depends on the shapes of the supply and the demand curves. More specifically, the incidence of an excise tax depends on the price elasticity of supply and the price elasticity of demand. We can see this by looking first at a case in which consumers pay most of an excise tax, and then at a case in which producers pay most of the tax.

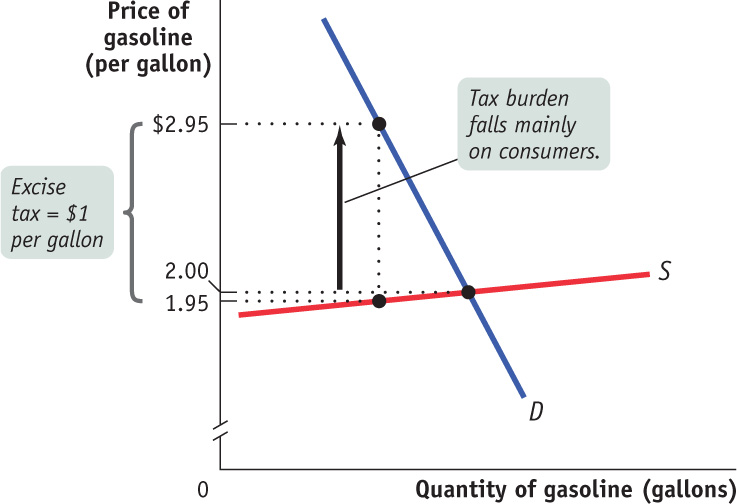

When an Excise Tax is Paid Mainly By ConsumersFigure 15-4 shows an excise tax that falls mainly on consumers: an excise tax on gasoline, which we set at $1 per gallon. (There really is a federal excise tax on gasoline, though it is actually only about $0.18 per gallon in the United States. In addition, states impose excise taxes between $0.08 and $0.37 per gallon.) According to Figure 15-4, in the absence of the tax, gasoline would sell for $2 per gallon.

FIGURE15-4An Excise Tax Paid Mainly by Consumers

Two key assumptions are reflected in the shapes of the supply and demand curves in Figure 15-4. First, the price elasticity of demand for gasoline is assumed to be very low, so the demand curve is relatively steep. Recall that a low price elasticity of demand means that the quantity demanded changes little in response to a change in price. Second, the price elasticity of supply of gasoline is assumed to be very high, so the supply curve is relatively flat. A high price elasticity of supply means that the quantity supplied changes a lot in response to a change in price.

We have just learned that an excise tax drives a wedge, equal to the size of the tax, between the price paid by consumers and the price received by producers. This wedge drives the price paid by consumers up and the price received by producers down. But as we can see from Figure 15-4, in this case those two effects are very unequal in size. The price received by producers falls only slightly, from $2.00 to $1.95, but the price paid by consumers rises by a lot, from $2.00 to $2.95. This means that consumers bear the greater share of the tax burden.

This example illustrates another general principle of taxation: When the price elasticity of demand is low and the price elasticity of supply is high, the burden of an excise tax falls mainly on consumers. Why? A low price elasticity of demand means that consumers have few substitutes and, therefore, little alternative to buying higher-

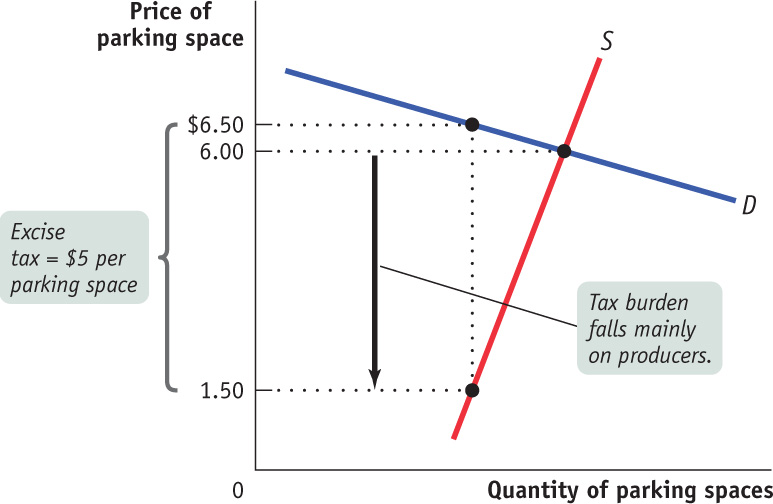

When an Excise Tax is Paid Mainly By ProducersFigure 15-5 shows an example of an excise tax paid mainly by producers, a $5.00 per day tax on downtown parking in a small city. In the absence of the tax, the market equilibrium price of parking is $6.00 per day.

FIGURE15-5An Excise Tax Paid Mainly by Producers

We’ve assumed in this case that the price elasticity of supply is very low because the lots used for parking have very few alternative uses. This makes the supply curve for parking spaces relatively steep. The price elasticity of demand, however, is assumed to be high: consumers can easily switch from the downtown spaces to other parking spaces a few minutes’ walk from downtown, spaces that are not subject to the tax. This makes the demand curve relatively flat.

The tax drives a wedge between the price paid by consumers and the price received by producers. In this example, however, the tax causes the price paid by consumers to rise only slightly, from $6.00 to $6.50, but the price received by producers falls a lot, from $6.00 to $1.50. In the end, a consumer bears only $0.50 of the $5 tax burden, with a producer bearing the remaining $4.50.

Again, this example illustrates a general principle: When the price elasticity of demand is high and the price elasticity of supply is low, the burden of an excise tax falls mainly on producers. A real-

Putting It All TogetherWe’ve just seen that when the price elasticity of supply is high and the price elasticity of demand is low, an excise tax falls mainly on consumers. And when the price elasticity of supply is low and the price elasticity of demand is high, an excise tax falls mainly on producers. This leads us to the general rule: When the price elasticity of demand is higher than the price elasticity of supply, an excise tax falls mainly on producers. When the price elasticity of supply is higher than the price elasticity of demand, an excise tax falls mainly on consumers.

So elasticity—

WHO PAYS THE FICA?

Anyone who works for an employer receives a paycheck that itemizes not only the wages paid but also the money deducted from the paycheck for various taxes. For most people, one of the big deductions is FICA, also known as the payroll tax. FICA, which stands for the Federal Insurance Contributions Act, pays for the Social Security and Medicare systems, federal social insurance programs that provide income and medical care to retired and disabled Americans.

In 2013, most American workers paid 7.65% of their earnings in FICA. (During 2011–

How should we think about FICA? Is it really shared equally by workers and employers? We can use our previous analysis to answer that question, because FICA is like an excise tax—

But we already know that the incidence of a tax does not really depend on who actually makes out the check. Almost all economists agree that FICA is a tax actually paid by workers, not by their employers. The reason for this conclusion lies in a comparison of the price elasticities of the supply of labor by households and the demand for labor by firms.

Evidence indicates that the price elasticity of demand for labor is quite high, at least 3. That is, an increase in average wages of 1% would lead to at least a 3% decline in the number of hours of work demanded by employers. Labor economists believe, however, that the price elasticity of supply of labor is very low. The reason is that although a fall in the wage rate reduces the incentive to work more hours, it also makes people poorer and less able to afford leisure time. The strength of this second effect is shown in the data: the number of hours people are willing to work falls very little—

Our general rule of tax incidence says that when the price elasticity of demand is much higher than the price elasticity of supply, the burden of an excise tax falls mainly on the suppliers. So the FICA falls mainly on the suppliers of labor, that is, workers—

This conclusion tells us something important about the American tax system: the FICA, rather than the much-

The Benefits and Costs of Taxation

When a government is considering whether to impose a tax or how to design a tax system, it has to weigh the benefits of a tax against its costs. We may not think of a tax as something that provides benefits, but governments need money to provide things people want, such as streets, schools, national defense, and health care for those unable to afford it. The benefit of a tax is the revenue it raises for the government to pay for these services. Unfortunately, this benefit comes at a cost—

The Revenue from an Excise Tax

How much revenue does the government collect from an excise tax? In our hotel tax example, the revenue is equal to the area of the shaded rectangle in Figure 15-6.

FIGURE15-6The Revenue from an Excise Tax

To see why this area represents the revenue collected by a $40 tax on hotel rooms, notice that the height of the rectangle is $40, equal to the tax per room. It is also, as we’ve seen, the size of the wedge that the tax drives between the supply price (the price received by producers) and the demand price (the price paid by consumers). Meanwhile, the width of the rectangle is 5,000 rooms, equal to the equilibrium quantity of rooms given the $40 tax. With that information, we can make the following calculations.

The tax revenue collected is:

Tax revenue = $40 per room × 5,000 rooms = $200,000

The area of the shaded rectangle is:

Area = Height × Width = $40 per room × 5,000 rooms = $200,000

or

Tax revenue = Area of shaded rectangle

This is a general principle: The revenue collected by an excise tax is equal to the area of a rectangle with the height of the tax wedge between the supply price and the demand price and the width of the quantity sold under the tax.

The Costs of Taxation

What is the cost of a tax? You might be inclined to answer that it is the amount of money taxpayers pay to the government—

No—

If these two sets of people were allowed to trade with each other without the tax, they would engage in mutually beneficial transactions—

So an excise tax imposes costs over and above the tax revenue collected in the form of inefficiency, which occurs because the tax discourages mutually beneficial transactions. The cost to society of this kind of inefficiency—

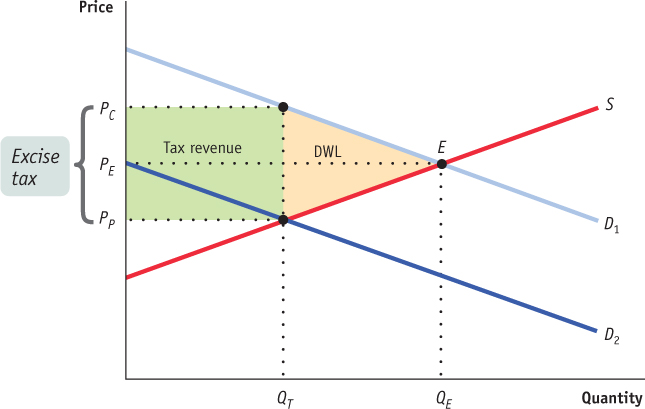

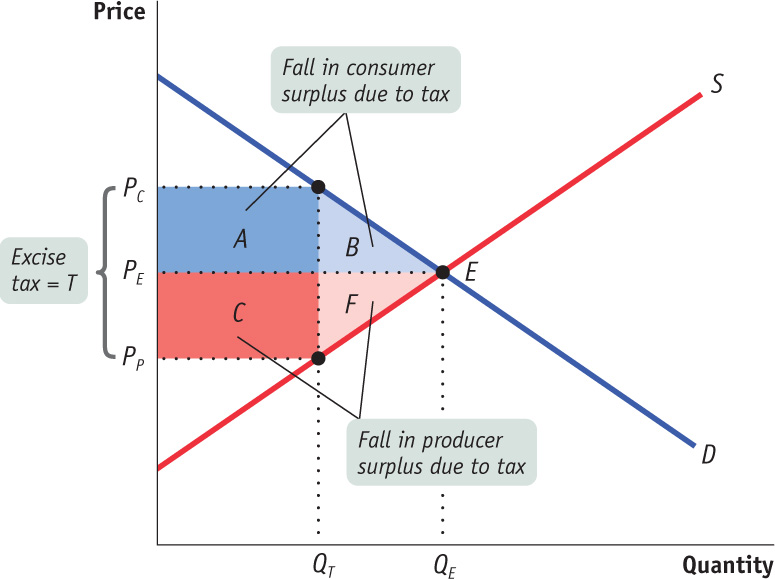

To measure the deadweight loss from a tax, we turn to the concepts of producer and consumer surplus. Figure 15-7 shows the effects of an excise tax on consumer and producer surplus. In the absence of the tax, the equilibrium is at E and the equilibrium price and quantity are PE and QE, respectively. An excise tax drives a wedge equal to the amount of the tax between the price received by producers and the price paid by consumers, reducing the quantity sold. In this case, with a tax of T dollars per unit, the quantity sold falls to QT. The price paid by consumers rises to PC, the demand price of the reduced quantity, QT, and the price received by producers falls to PP, the supply price of that quantity. The difference between these prices, PC − PP, is equal to the excise tax, T.

FIGURE15-7A Tax Reduces Consumer and Producer Surplus

Using the concepts of producer and consumer surplus, we can show exactly how much surplus producers and consumers lose as a result of the tax. We learned previously that a fall in the price of a good generates a gain in consumer surplus that is equal to the sum of the areas of a rectangle and a triangle. Similarly, a price increase causes a loss to consumers that is represented by the sum of the areas of a rectangle and a triangle. So it’s not surprising that in the case of an excise tax, the rise in the price paid by consumers causes a loss equal to the sum of the areas of a rectangle and a triangle: the dark blue rectangle labeled A and the area of the light blue triangle labeled B in Figure 15-7.

Meanwhile, the fall in the price received by producers leads to a fall in producer surplus. This, too, is equal to the sum of the areas of a rectangle and a triangle. The loss in producer surplus is the sum of the areas of the dark red rectangle labeled C and the light red triangle labeled F in Figure 15-7.

Of course, although consumers and producers are hurt by the tax, the government gains revenue. The revenue the government collects is equal to the tax per unit sold, T, multiplied by the quantity sold, QT. This revenue is equal to the area of a rectangle QT wide and T high. And we already have that rectangle in the figure: it is the sum of rectangles A and C. So the government gains part of what consumers and producers lose from an excise tax.

But a portion of the loss to producers and consumers from the tax is not offset by a gain to the government—

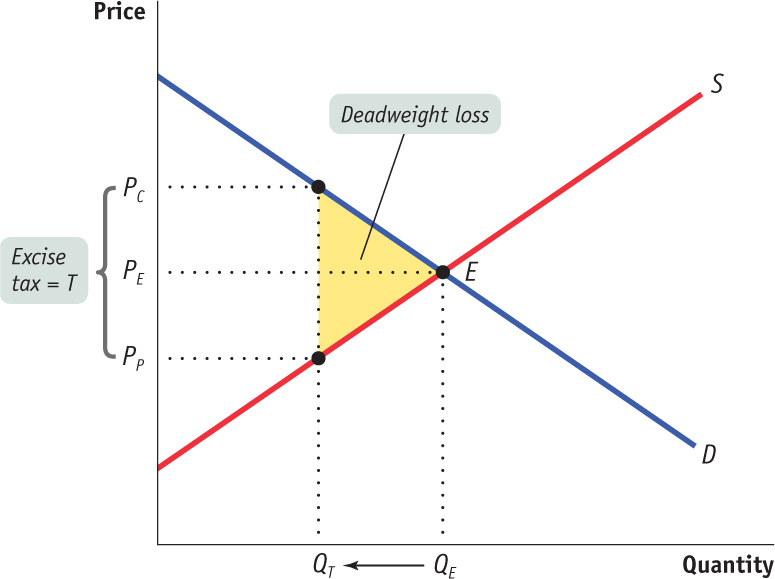

Figure 15-8 is a version of Figure 15-7 that leaves out rectangles A (the surplus shifted from consumers to the government) and C (the surplus shifted from producers to the government) and shows only the deadweight loss, drawn here as a triangle shaded yellow. The base of that triangle is equal to the tax wedge, T; the height of the triangle is equal to the reduction in the quantity transacted due to the tax, QE − QT. Clearly, the larger the tax wedge and the larger the reduction in the quantity transacted, the greater the inefficiency from the tax.

FIGURE15-8The Deadweight Loss of a Tax

But also note an important, contrasting point: if the excise tax somehow didn’t reduce the quantity bought and sold in this market—

Using a triangle to measure deadweight loss is a technique used in many economic applications. For example, triangles are used to measure the deadweight loss produced by types of taxes other than excise taxes. They are also used to measure the deadweight loss produced by monopoly, another kind of market distortion. And deadweight-

The administrative costs of a tax are the resources used by government to collect the tax, and by taxpayers to pay (or to evade) it, over and above the amount collected.

In considering the total amount of inefficiency caused by a tax, we must also take into account something not shown in Figure 15-8: the resources actually used by the government to collect the tax, and by taxpayers to pay it, over and above the amount of the tax. These lost resources are called the administrative costs of the tax. The most familiar administrative cost of the U.S. tax system is the time individuals spend filling out their income tax forms or the money they spend on accountants to prepare their tax forms for them. (The latter is considered an inefficiency from the point of view of society because accountants could instead be performing other, non-

Included in the administrative costs that taxpayers incur are resources used to evade the tax, both legally and illegally. The costs of operating the Internal Revenue Service, the arm of the federal government tasked with collecting the federal income tax, are actually quite small in comparison to the administrative costs paid by taxpayers. The total inefficiency caused by a tax is the sum of its deadweight loss and its administrative costs.

A lump-

Some extreme forms of taxation, such as the poll tax instituted by the government of British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher in 1989, are notably unfair but very efficient. A poll tax is an example of a lump-

Under the old system, the highest local taxes were paid by the people with the most expensive houses. Because these people tended to be wealthy, they were also best able to bear the burden. But the old system definitely distorted incentives to engage in mutually beneficial transactions and created deadweight loss. People who were considering home improvements knew that such improvements, by making their property more valuable, would increase their tax bills. The result, surely, was that some home improvements that would have taken place without the tax did not take place because of it.

In contrast, a lump-

15

Solutions appear at the back of the book.

Check Your Understanding

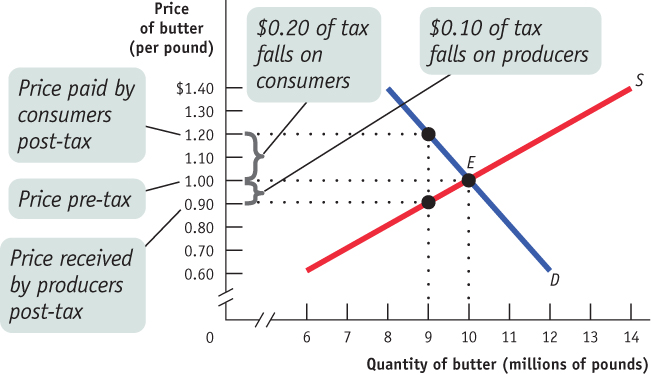

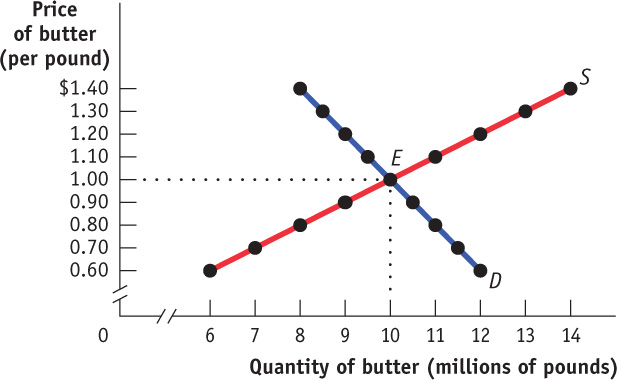

1. Consider the market for butter, shown in the accompanying figure. The government imposes an excise tax of $0.30 per pound of butter. What is the price paid by consumers post-

2. The accompanying table shows five consumers’ willingness to pay for one can of diet soda each as well as five producers’ costs of selling one can of diet soda each. Each consumer buys at most one can of soda; each producer sells at most one can of soda. The government asks your advice about the effects of an excise tax of $0.40 per can of diet soda. Assume that there are no administrative costs from the tax.

| Consumer | Willingness to Pay | Producer | Cost |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ana | $0.70 | Zhang | $0.10 |

| Bernice | 0.60 | Yves | 0.20 |

| Chizuko | 0.50 | Xavier | 0.30 |

| Dagmar | 0.40 | Walter | 0.40 |

| Ella | 0.30 | Vern | 0.50 |

-

a. Without the excise tax, what is the equilibrium price and the equilibrium quantity of soda?

Without the excise tax, Zhang, Yves, Xavier, and Walter sell, and Ana, Bernice, Chizuko, and Dagmar buy one can of soda each, at $0.40 per can. So the quantity bought and sold is 4. -

b. The excise tax raises the price paid by consumers post-

tax to $0.60 and lowers the price received by producers post- tax to $0.20. With the excise tax, what is the quantity of soda sold? With the excise tax, Zhang and Yves sell, and Ana and Bernice buy one can of soda each. So the quantity sold is 2. -

c. Without the excise tax, how much individual consumer surplus does each of the consumers gain? How much individual consumer surplus does each consumer gain with the tax? How much total consumer surplus is lost as a result of the tax?

Without the excise tax, Ana’s individual consumer surplus is $0.70 − $0.40 = $0.30, Bernice’s is $0.60 − $0.40 = $0.20, Chizuko’s is $0.50 − $0.40 = $0.10, and Dagmar’s is $0.40 −$0.40 = $0.00. Total consumer surplus is $0.30 + $0.20 + $0.10 + $0.00 = $0.60. With the tax, Ana’s individual consumer surplus is $0.70 − $0.60 = $0.10 and Bernice’s is $0.60 − $0.60 = $0.00. Total consumer surplus post-tax is $0.10 + $0.00 = $0.10. So the total consumer surplus lost because of the tax is $0.60 − $0.10 = $0.50. -

d. Without the excise tax, how much individual producer surplus does each of the producers gain? How much individual producer surplus does each producer gain with the tax? How much total producer surplus is lost as a result of the tax?

Without the excise tax, Zhang’s individual producer surplus is $0.40 − $0.10 = $0.30, Yves’s is $0.40 − $0.20 = $0.20, Xavier’s is $0.40 − $0.30 = $0.10, and Walter’s is $0.40 − $0.40 = $0.00. Total producer surplus is $0.30 + $0.20 + $0.10 + $0.00 = $0.60. With the tax, Zhang’s individual producer surplus is $0.20 − $0.10 = $0.10 and Yves’s is $0.20 − $0.20 = $0.00. Total producer surplus post-tax is $0.10 + $0.00 = $0.10. So the total producer surplus lost because of the tax is $0.60 − $0.10 = $0.50. -

e. How much government revenue does the excise tax create?

With the tax, two cans of soda are sold, so the government tax revenue from this excise tax is 2 × $0.40 = $0.80. -

f. What is the deadweight loss from the imposition of this excise tax?

Total surplus without the tax is $0.60 + $0.60 = $1.20. With the tax, total surplus is $0.10 + $0.10 = $0.20, and government tax revenue is $0.80. So deadweight loss from this excise tax is $1.20 − ($0.20 + $0.80) = $0.20.

Multiple-

Question

1. An excise tax imposed on sellers in a market will result in which of the following?

I. an upward shift of the supply curve

II. a downward shift of the demand curve

III. deadweight loss

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

| E. |

Question

2. An excise tax will be paid mainly by producers when

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

| E. |

Critical-

Draw a correctly labeled graph of a competitive market in equilibrium. Use your graph to illustrate the effect of an excise tax imposed on consumers. Indicate each of the following on your graph:

- a. the equilibrium price and quantity without the tax, labeled PE and QE

- b. the quantity sold in the market post-

tax, labeled QT - c. the price paid by consumers post-

tax, labeled PC - d. the price received by producers post-

tax, labeled PP - e. the tax revenue generated by the tax, labeled “Tax revenue”

- f. the deadweight loss resulting from the tax, labeled “DWL”

- g. the wedge created by the tax between PC and PP, labeled “Excise tax”