Many prokaryotes form complex communities

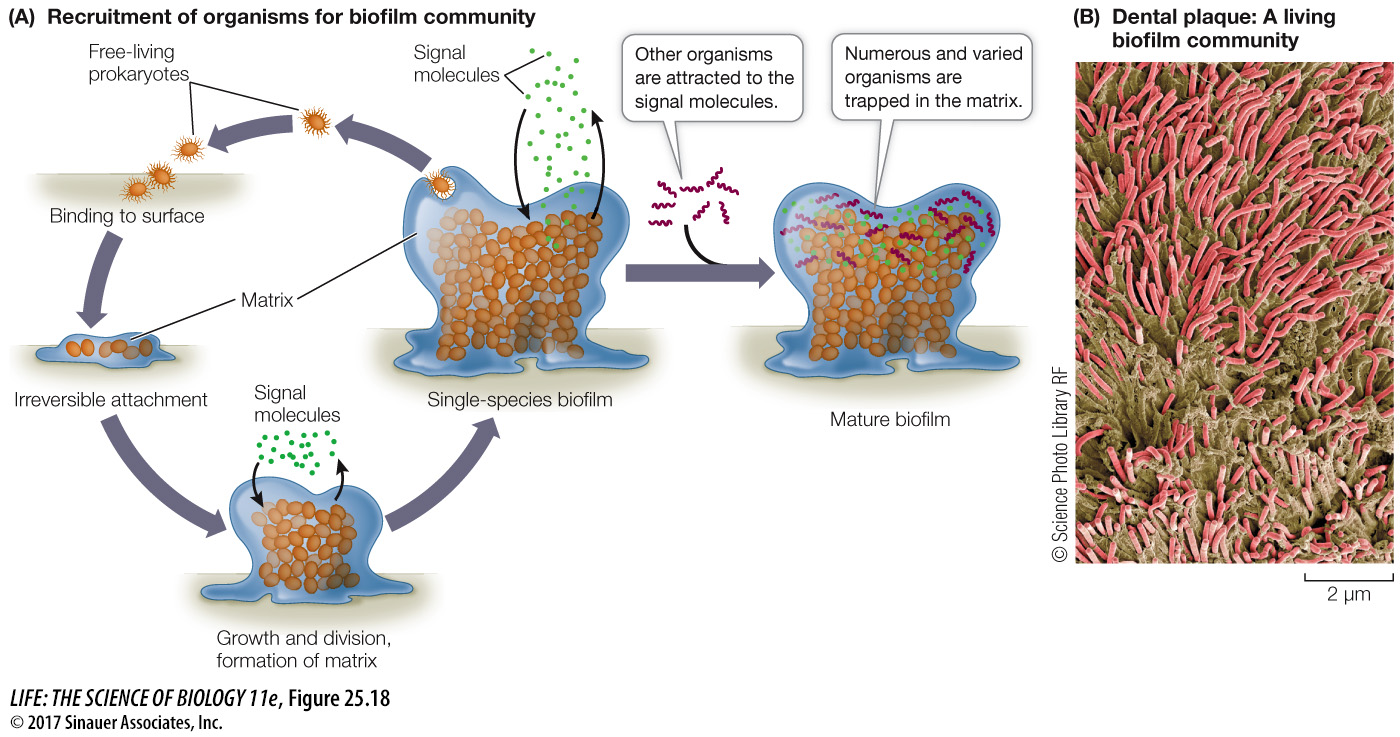

Some microbial communities form layers in sediments, and others form clumps a meter or more in diameter. Many microbial communities tend to form dense biofilms. Upon contacting a solid surface, the cells bind to that surface and secrete a sticky, gel-like polysaccharide matrix that traps other cells (Figure 25.18). Once a biofilm forms, the cells become more difficult to kill.

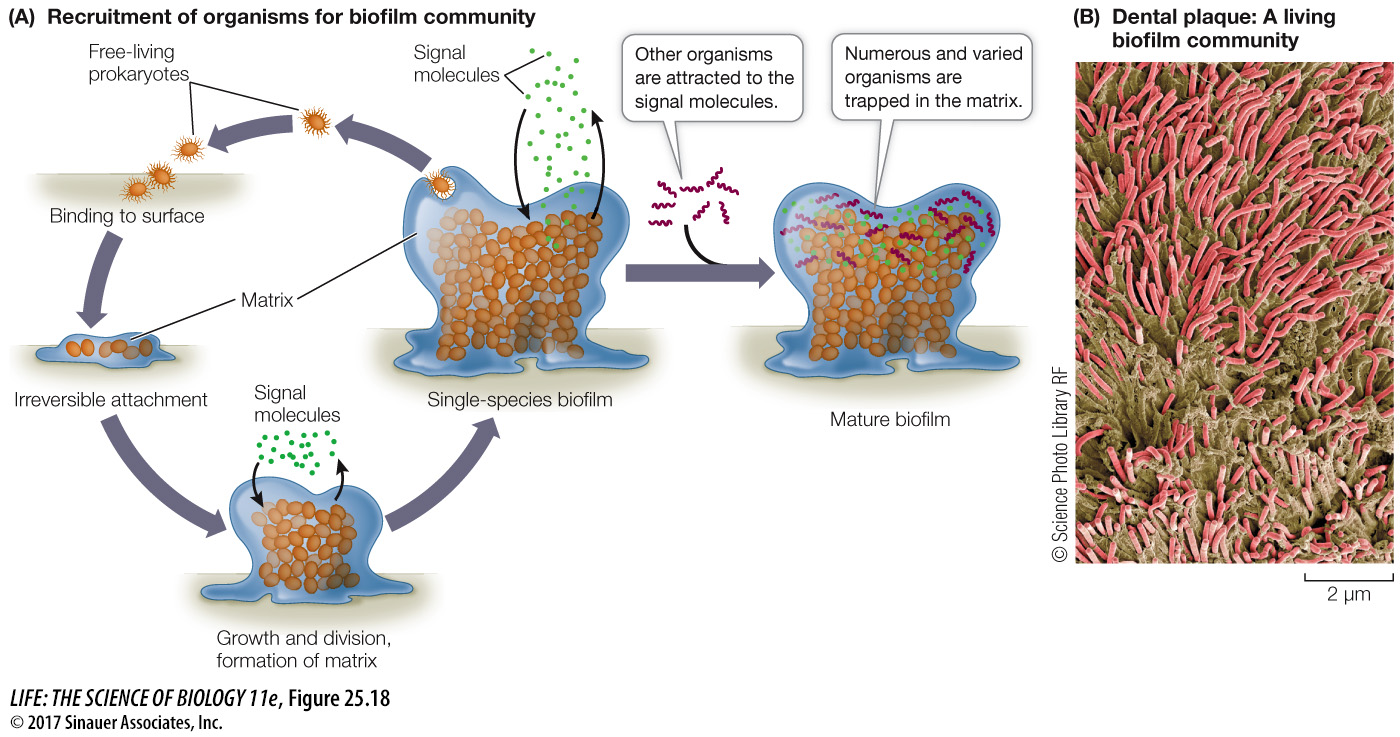

Figure 25.18 Forming a Biofilm (A) Free-living prokaryotes readily attach themselves to surfaces and form films that are stabilized and protected by a surrounding matrix. Once the population is large enough, the developing biofilm can send out chemical signals that attract other microorganisms. (B) Scanning electron micrography reveals a biofilm of dental plaque. The bacteria (red) are embedded in a matrix consisting of proteins from both bacterial secretions and saliva.

Biofilms are found in many places, and in some of those places they cause problems for humans. The material on our teeth that we call dental plaque is a biofilm. Pathogenic bacteria are difficult for the immune system—and modern medicine—to combat once they form a biofilm, which may be impermeable to antibiotics. Worse, some drugs stimulate the bacteria in a biofilm to lay down more matrix, making the film even more impermeable. Biofilms may form on just about any available surface, including contact lenses and artificial joint replacements. They foul metal pipes and cause corrosion, a major problem in steam-driven electricity generation plants. Fossil stromatolites—large, rocky structures made up of alternating layers of fossilized biofilm and calcium carbonate—are among the oldest remnants of life on Earth (see Figure 24.9B).

Some biologists are studying the chemical signals that prokaryotes use to communicate with one another and that trigger density-linked activities such as biofilm formation. We saw one example of this type of communication—called quorum sensing—in the chapter-opening discussion of bioluminescent Vibrio. How does quorum sensing work? As demonstrated in Investigating Life: How Do Bacteria Communicate with One Another?, individual Vibrio bacteria can excrete a signal that is detected by other individuals, and this signal then functions to turn on the genes that produce luciferase—an enzyme that produces bioluminescence when it is active.