Johann Sebastian Bach, Brandenburg Concerto No. 5, for Flute, Violin, Harpsichord, and Orchestra (before 1721)

“I Shall

1. set the boys a shining example of an honest, retiring manner of life, serve the School industriously, and instruct the boys conscientiously

2. Bring the music in both the principal Churches of this town [Leipzig] into a good state, to the best of my ability

3. Show to the Honorable and Most Wise Town Council all proper respect and obedience.”

Bach’s contract at Leipzig, 1723 — the first three of fourteen stipulations

A concerto grosso is a concerto for a group of several solo instruments (rather than just a single one) and orchestra. In 1721 Johann Sebastian Bach sent a beautiful manuscript containing six of these works to the margrave of Brandenburg, a minor nobleman with a paper title — the duchy of Brandenburg had recently been merged into the kingdom of Prussia, Europe’s fastest-

To impress the margrave, presumably, Bach sent pieces with six different combinations of instruments, combinations that in some cases were never used before or after. Taken as a group, the Brandenburg Concertos present an unsurpassed anthology of dazzling tone colors and imaginative treatments of the concerto contrast between soloists and orchestra.

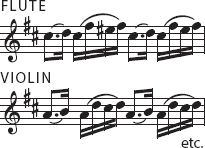

Brandenburg Concerto No. 5 features as its solo group a flute, violin, and harpsichord. The orchestra is the basic Baroque string orchestra (see page 108). The harpsichordist of the solo group doubles as the player of the orchestra’s continuo chords, and the solo violin leads the orchestra during the ritornellos.

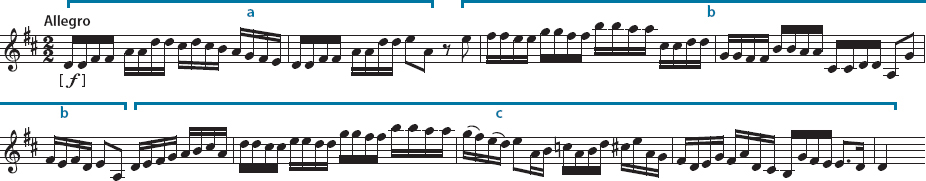

First Movement (Allegro) In ritornello form, the first movement of Brandenburg Concerto No. 5 opens with a loud, bright, solid-

Once the ritornello ends with a solid cadence, the three solo instruments enter with rapid imitative polyphony. They dominate the rest of the movement. They introduce new motives and new patterns of figuration, take over some motives from the ritornello, and toss all these musical ideas back and forth between them. Every so often, the orchestra breaks in again, always with clear fragments of the ritornello, in various keys. All this makes an effect very, very different from Vivaldi’s Violin Concerto in G and Spring concerto, not only because of the sheer length of the movement but also because of the richness of the counterpoint and the harmony.

During a particularly striking solo section in the minor mode (the first section printed in blue in Listening Chart 5), the soloists abandon their motivic style and play music with even richer harmonies and intriguing, special textures. After this, you may be able to hear that all the remaining solos are closely related to solos heard before the minor-

An improvised or improvisatory solo passage of this kind within a larger piece is called a cadenza. Cadenzas are a feature of concertos in all eras; the biggest cadenza always comes near the end of the first movement, as in Brandenburg Concerto No. 5.

In this cadenza, the harpsichord breaks out of the regular eighth-

Finally the whole ritornello is played, exactly as at the beginning; after nine minutes of rich and complex music, we hear it again as a complete and solid entity, not in fragments.

Second Movement (Affettuoso) After the forceful first movement, a change is needed: something quieter, slower, and more emotional (affettuoso means just that, emotional). As often in concertos, this slow movement is in the minor mode, contrasting with the first and last, which are in the major.

Baroque composers had a simple way of reducing volume: They could omit many or even all of the orchestra instruments. So here Bach employs only the three solo instruments — flute, violin, and harpsichord — plus the orchestra cello playing the continuo bass.

Third Movement (Allegro) The full orchestra returns in the last movement, which, however, begins with a lengthy passage for the three soloists in imitative, or fugal style (see the next section of this chapter). The lively compound meter with its triple component — one two three four five six — provides a welcome contrast to the duple meter of the two earlier movements.