George Frideric Handel, Julius Caesar (1724)

As a young man, Handel wrote a few German operas for the Hamburg opera company (most of the music is lost) and a few Italian operas for theaters in Florence and Venice. In his maturity he wrote as many as forty Italian operas for London, where he helped start a fad for imported Italian opera. Probably the most famous of them is Julius Caesar (Giulio Cesare in Egitto), one of a trio of Handel masterpieces written in the years 1724–

Background Like most opera seria of the late Baroque era, Julius Caesar draws on Roman history. Cleopatra, the famous queen of Egypt, applied her formidable charms to Julius Caesar and then, after Caesar’s assassination, also to his successor Mark Antony. Shakespeare deals with the second of these famous affairs in his play Antony and Cleopatra; Handel tackles the first.

Handel’s librettist added a great deal of nonhistorical plot material. History tells that Pompey — who comes into the story because he waged war on Caesar and lost and fled to Egypt — was murdered by one of his soldiers, but in the opera the murderer is Cleopatra’s brother Ptolemy. Pompey’s widow, Cornelia, is thrown into Ptolemy’s harem and has to resist his advances (among others’). Her son Sextus rattles around the opera swearing vengeance on Ptolemy and finally kills him. The historical Cleopatra poisoned Ptolemy, but her character in the opera is whitewashed, and she gets to sing some of the most ravishing, seductive music while disguised as her own maid. All this gives a taste of the typical complications in an opera seria plot.

Although the role of Sextus, for mezzo-

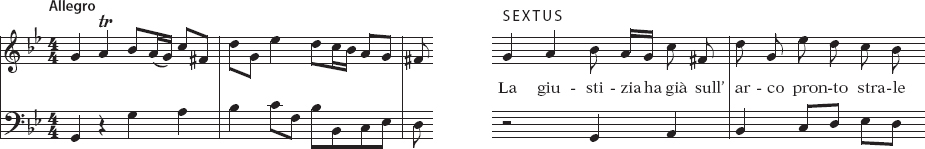

Aria, “La giustizia” Sextus promises revenge on Ptolemy, not for the first time, in the aria “La giustizia” (Justice). This aria is preceded — or, rather, set up — by a recitative (as usual). Since it makes more sense to study recitative when the words are in English, we leave that discussion until we get to Handel’s Messiah.

The aria starts with a ritornello played by the string orchestra, like the opening section of a concerto movement (see page 116). It establishes the mood right away:

The “affect” Handel means to convey by this strenuous, vigorous music is anger, and Sextus starts up with the same music. We will hear this ritornello three more times, once in a shortened form, prior to the second A section.

Apart from this shortened ritornello, “La giustizia” is in strict A B A (da capo) form. In the A section Handel goes through the words three times, with the orchestra interjecting to allow the singer to catch her breath. (These short spacers are not marked in the Listen box.) Notice how the music tends to explode angrily on certain key words, principally by the use of coloratura (fast scales and turns), as on “ven-

There is a flamboyant effect typical of the Baroque near the end of A, where Sextus dramatically comes to a stop. After a breathless pause, he moves on to make a very forceful final cadence. Revenge is nigh!

The aria’s B section introduces new words and some new keys for contrast; both features are typical in da capo arias. Otherwise it is brief and seems rather subdued — the strings drop out, leaving only the continuo as accompaniment. What the audience is waiting for is the repeat of A, where we can forget about Sextus and get to admire a display of vocal virtuosity. Lorraine Hunt Lieberson, the singer on our recording, adds brilliant improvised flourishes to the high notes on “pu-

Vocal cadenzas at the time were short, because they were supposed to be sung in a single breath — thus showing off virtuoso breath control as well as vocal technique and inventiveness.

LISTEN

Handel, Julius Caesar, Aria “La giustizia”

| For a note on Italian pronunciation, see page 85: “La joostidzia (ah) jah sool arco.” | ||||

| 0:00 | A | RITORNELLO | ||

| 0:16 | St. 1: first time | La giustizia ha già sull’ arco | Justice now has in its bow | |

| Pronto strale alla vendetta | The arrow primed for vengeance | |||

| Per punire un traditor | To castigate a traitor! | |||

| 0:50 | St. 1: second time | La giustizia . . . etc. | ||

| 1:10 | St. 1: third time | La giustizia . . . etc. | ||

| 1:31 | RITORNELLO | |||

| 1:47 | B | St. 2: | Quanto è tarda la saetta | The later the arrow is shot, |

| Tanto più crudele aspetta | The crueler is the pain suffered | |||

| La sua pena un empio cor. | By a dastardly heart! | |||

| 2:15 | A | RITORNELLO (abbreviated) | ||

| 2:22 | La giustizia . . . etc. | Justice . . . etc. | ||