Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Symphony No. 40 in G Minor, K. 550* (1788)

Mozart’s Symphony in G Minor is one of the most famous and admired of all his works. The opening movement, with its sharp contrasts and clear demarcations, makes an arresting introduction to sonata form.

Not many Classical compositions convey as dark and uneasy a mood as does this symphony. (Not many Classical symphonies are in the minor mode.) It suggests some kind of muted struggle against inescapable constraints. Mozart’s themes alone would not have created this effect; expressive as they are in themselves, they only attain their full effect in their setting. Mozart needed sonata form to manage these expressive themes — in a sense, to give them something to struggle against.

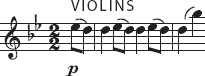

We have already cited the first movement’s opening texture — melody with a strictly homophonic accompaniment — as characteristic of the Viennese Classical style (see page 158). So also are the delicate dynamic changes toward the end of the theme and the loud repeated cadences that terminate it. The unique nervous energy of this theme, a blend of refinement and subdued agitation, stamps the first movement unforgettably.

Exposition The first theme is played twice. The second playing already begins the modulation to the exposition’s second key, and a forceful bridge passage completes this process, after which the music comes to an abrupt stop. Such stops will come again and again in this movement.

The second theme, in the major mode, is divided up, measure by measure or phrase by phrase, between the strings and the woodwinds:

Then it is repeated with the role of the instruments reversed, the strings taking the notes originally played by the winds, and vice versa. These instrumental alterations contribute something absolutely essential to the character of the theme, and show Mozart’s fine ear for tone color, or timbre.

The second appearance of the second theme does not come to a cadence, but runs into a series of new ideas that make up the rest of the second group. All of them are brief and leave little impression on the rest of the movement, so it is best not to consider these ideas actual themes. One of these ideas repeats the motive of the first theme.

A short cadence theme, forte, and a very insistent series of repeated cadences bring the exposition to a complete stop. (We still hear the rhythm of theme 1.) After one dramatic chord, wrenching us back from major to the original minor key, the whole exposition is repeated.

Development Two more dramatic chords — different chords — and then the development section starts quietly. The first theme is accompanied as before. It modulates (changes key) at once, and seems to be losing itself in grief, until the rest of the orchestra bursts in with a furious contrapuntal treatment of that tender, nervous melody.

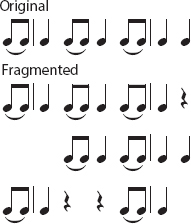

The music seems to exhaust itself. It comes to another stop. But in the following piano passage, the modulations continue, with orchestral echoes based on smaller and smaller portions of the first theme. Breaking up a theme in this way is called fragmentation.

Passion breaks out anew in another forte passage; but the modulations have finally ceased. The fragmentation reaches its final stage. At last the harmony seems to be waiting or preparing for something, rather than shifting all the time. This passage is the retransition.

Recapitulation After its fragmentation in the development section, the first theme somehow conveys new pathos when it returns in its original form, and in the original tonic key. The bassoon has a beautiful new descending line.

And pathos deepens when the second theme and all the other ideas in the second group — originally heard in a major-

Coda In a very short coda, Mozart refers one last time to the first theme. It sounds utterly disheartened, and then battered by the usual repeated cadences.

* Mozart’s works are identified by K numbers, after the chronological catalog of his works compiled by Ludwig von Köchel. The first edition (1862) listed 626 works composed by Mozart in his short lifetime; later editions add many more that have come to light since then.