Double-Exposition Form

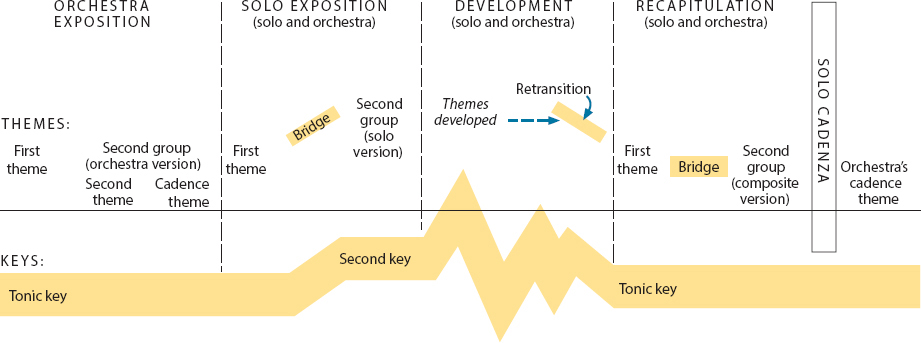

For the first movements of concertos, Mozart developed a special form to capitalize on the contest that is basic to the genre. Though the diagram for double-exposition form may look rather cluttered, it is in fact simply an extended variant of sonata form. Compare the sonata-form diagram on page 165:

“These piano concertos are a happy medium between too easy and too difficult; they are very brilliant, pleasing to the ear, and natural, without being simple-minded. There are passages here and there which only connoisseurs will be able to appreciate, but less learned listeners will like them too, without knowing why.”

Letter from Mozart to his father, 1782

In sonata form, the exposition presenting all the basic material is repeated. In the concerto, instead, each of the competing forces presents the musical themes in its own somewhat different version. The two times through the exposition of a symphony, in other words, are here apportioned between the orchestra (first time) and the soloist (second time). But the two statements of the concerto exposition differ not merely in the instruments that play them. Unlike the exposition in a symphony, in a concerto the orchestra exposition does not modulate. The change of key (which counts for so much in sonata-form composition) is saved until the solo exposition. The listener senses that the orchestra can’t modulate and the soloist can — evidence of the soloist’s superior range and mobility. This is demonstrated spectacularly by the soloist playing scales, arpeggios, and other brilliant material, making the solo exposition longer than the orchestral one.

The recapitulation in double-exposition form amounts to a composite of the orchestral and solo versions of the exposition. Typically the orchestra’s cadence theme, which has been crowded out of the solo exposition to make room for virtuoso activity, returns at the end to make a very satisfactory final cadence.* Shortly before the end, there is a big, formal pause for the soloist’s cadenza (see page 124). The soloist would improvise at this point — to show his or her skill and flair by working out new thematic developments on the spot, and also by carrying off brilliant feats of virtuosity.