Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–1791), Piano Concerto No. 23 in A, K. 488 (1786)

This favorite Mozart concerto proceeds from one of his most gentle and songful first movements to a second movement that is almost tragic, followed by an exuberant, sunny finale. The first movement might almost have been intended as a demonstration piece for double-

No fewer than four themes in this movement could be described as gentle and songful — though always alert. For a work of this character, Mozart uses a reduced orchestra, keeping the mellow clarinets but omitting the sharper-

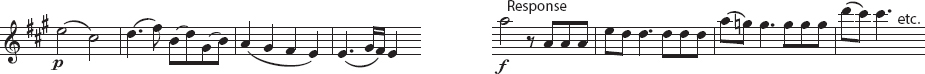

Orchestra Exposition Theme 1, played piano by the strings and repeated by the woodwinds, is answered by a vigorous forte response in the full orchestra.

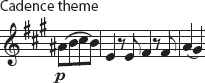

This response idea returns many times, balancing the quiet themes, and often leading to something new — here, theme 2, another quiet melody, full of feeling. An agitated passage interrupts, suddenly emotional, touching on two different minor keys, but only briefly. This whole section remains in the major tonic key, without any actual modulation. The cadence theme that ends the section maintains the gentle mood.

Solo Exposition The solo exposition expands on and illuminates the orchestra exposition, with the piano taking over some of it, while also adding fast-

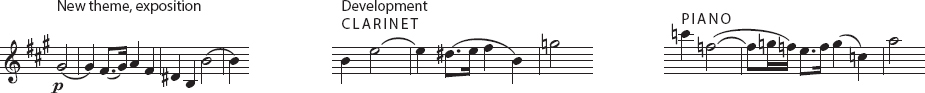

Showy cadences of this kind are a regular feature of Classical concertos; the orchestra always answers with loud music of its own, like a cheer. Here it is the orchestra’s response passage again. But this time it stops in midcourse, as though the orchestra has suddenly remembered something intimate and a little serious. A new theme (yet another quiet, gentle melody, this time with a thoughtful character) appears out of nowhere:

After the orchestra plays the new theme, the solo repeats it in an elaborated version, and we slip into the development section.

Development The basic idea behind concertos, the contest between orchestra and soloist, is brought out wonderfully here. Mozart sets up a rapid-

The new theme turns unexpectedly anxious in the retransition (see the music in the margin, to the right). Finally, with a brief cadenza, the piano pulls out of the dialogue and steers the way to the recapitulation.

Recapitulation At the start of the movement, the songful first theme was claimed in turn by the orchestra and the solo in their respective expositions. In the recapitulation, a composite of the two expositions, they share it.

Otherwise, the recapitulation resembles the solo exposition, though the bridge is altered so that the whole remains in the tonic key. There is a beautiful extension at the end, and when the response passage comes again, it leads to a heavy stop, with a fermata — the standard way for the orchestra to bow out, after preparing for the soloist’s grand re-

The solo’s showy cadence at the end of the cadenza is cheered along once again by the orchestra’s response passage, which we have heard so many times before. This time it leads to something we have not heard many times — only once, nine minutes back: the quiet cadence theme of the orchestra exposition. Do you remember it? It makes a perfect ending for the whole movement, with an extra twist: a little flare-