Hector Berlioz, Fantastic Symphony: Episodes in the Life of an Artist (1830)

Clearly Berlioz had a gift for public relations, for the program of his Fantastic Symphony was not a familiar play or novel, but an autobiographical fantasy of the most lurid sort. Here was music that encouraged listeners to think it had been written under the influence of opium, the drug of choice among the Romantics, which shocked society at large. What is more, half of Paris knew that Berlioz was madly in love (from afar) with an Irish actress, Harriet Smithson, who had taken the city by storm with her Shakespearean roles.

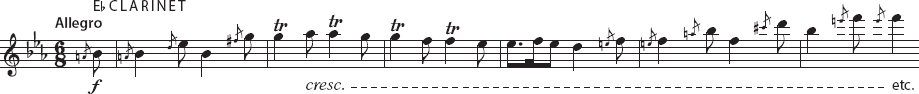

Audiences have never been quite sure how seriously to take it all, but they continue to be bowled over by the sheer audacity of the whole conception and the rambunctious way it is realized. Then there are the young Berlioz’s effects of tone color. He demanded an orchestra of unprecedented size (see page 231!), which he used in the most original and imaginative ways. Also highly original was the notion of having a single theme recur in all the movements as a representation of the musician’s beloved — his idée fixe or obsession, the Shakespearean Smithson. Here is the idée fixe theme as it first appears:

Berlioz’s expressive terms translate as follows:

Canto espressivo = expressive song

dolce = sweetly

poco = somewhat

poco a poco = bit by bit

animato = animated

ritenuto = slowed down (ritardando)

a tempo = back to the original tempo

This typically Romantic melody takes its yearning quality from its slow struggle to move higher and higher in pitch; from measure 5 on, each phrase peaks a bit above the preceding phrase until the melody reaches its climax at measure 15. Near the end, measure 19 provides a positive shudder of emotion. Notice how many dynamic, rubato, and other marks Berlioz has supplied, trying to ensure just the right expressive quality from moment to moment.

To illustrate the drastic mood swings described in his program, Berlioz subjects the idée fixe to thematic transformation (see page 232) for all its other appearances in the opium dream. The last movement, for example, has a grotesque parody of the theme. Its new jerky rhythm and squeaky orchestration (using the small E-

From Berlioz’s Program: Movement 1

First he recalls the soul-

First Movement: Reveries, Passions (Largo — Allegro agitato e appassionato assai) We first hear a short, quiet run-

This fast section follows sonata form, but only very loosely. The idée fixe is the main theme, and a second theme is simply a derivative of the first. Some of the finest strokes in this movement run counter to Classical principles — for example, the arresting up-

Near the end, beginning a very long coda, the idée fixe returns loudly at a faster tempo — the first of its many transformations. At the very end, slower music depicts the program’s “religious consolations.”

Movement 2

He encounters his beloved at a ball, in the midst of a noisy, brilliant party.

Second Movement: A Ball (Allegro non troppo) A symphony needs the simplicity and easy swing of a dance movement, and this ballroom episode of the opium dream conveniently provides one. The dance in question is not a minuet or a scherzo, but a waltz, the most popular ballroom dance of the nineteenth century. The idée fixe, transformed into a lilting triple meter, first appears in the position of the trio (B in the A B A form) and then returns hauntingly in a coda.

Movement 3

He hears two shepherds piping in dialogue. The pastoral duet, the location, the light rustling of trees stirred gently by the wind, some newly conceived grounds for hope — all this gives him a feeling of unaccustomed calm. But she appears again . . . what if she is deceiving him?

Third Movement: Scene in the Country (Adagio) Invoking nature to reflect human emotions was a favorite Romantic procedure. The “pastoral duet” is played by an English horn and an offstage oboe (boy and girl, perhaps?). At the end, the English horn returns to the accompaniment of distant thunder sounds, played on four differently tuned timpani. Significantly, the oboe can no longer be heard.

In this movement the idée fixe returns in a new, strangely agitated transformation. It is interrupted by angry sounds swelling to a climax, reflecting the anxieties chronicled in the program.

Movement 4

He dreams he has killed his beloved, that he is condemned to death and led to execution. A march accompanies the procession, now gloomy and wild, now brilliant and grand. Finally the idée fixe appears for a moment, to be cut off by the fall of the ax.

Fourth Movement: March to the Scaffold (Allegretto non troppo) This movement has two main themes: a long downward scale (“gloomy and wild”) and an exciting military march (“brilliant and grand”), orchestrated more like a football band than a symphony orchestra. Later the scale theme appears divided up in its orchestration between plucked and bowed strings, woodwinds, brass, and percussion — a memorable instance of Berlioz’s novel imagination for tone color. The scale theme also appears in a truly shattering inverted form (that is, moving up instead of down).

Berlioz had written this march or something like it several years earlier. As he revised it to go into the Fantastic Symphony, he added a coda that uses the idée fixe and therefore only makes sense in terms of the symphony’s program. The final fall of the ax is illustrated musically by the sound of a guillotine chop and a military snare-

Fifth Movement: Dream of a Witches’ Sabbath (Larghetto — Allegro) Adding a fifth movement to the traditional four of the Classical symphony was a typical Berlioz innovation (although it can be traced back to the Beethoven he so admired). Now the element of parody is added to the astonishing orchestral effects pioneered earlier in the symphony. First we hear the unearthly sounds of the nighttime locale of the witches’ orgy. Their swishing broomsticks are heard, and distant, echoing horn calls summon them. Mutes are used in the brass instruments — perhaps the first time mutes were ever used in a poetic way.

Movement 5

He finds himself at a Witches’ Sabbath. . . . Unearthly sounds, groans, shrieks of laughter, distant cries echoed by other cries. The beloved’s melody is heard, but it has lost its character of nobility and timidity. It is she who comes to the Sabbath! At her arrival, a roar of joy. She joins in the devilish orgies. A funeral knell; burlesque of the Dies irae.

As Berlioz remarks, the “noble and timid” idée fixe sounds thoroughly vulgar in its last transformation, played in a fast jig rhythm by the shrill E-

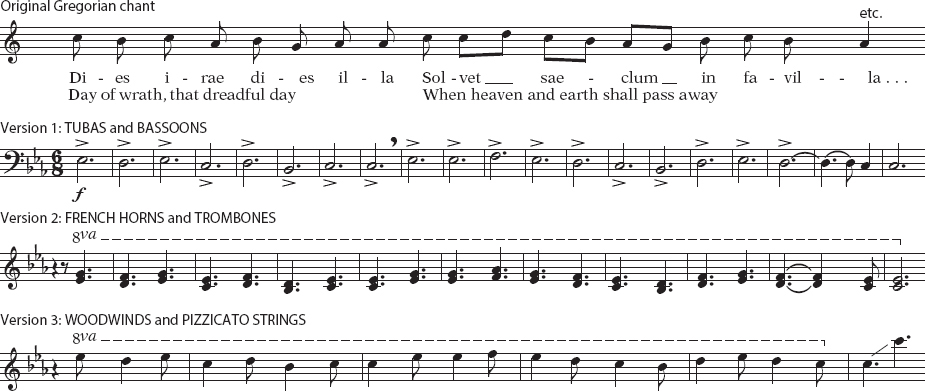

As the merriment is brought to an end by the tolling of funeral bells, Berlioz prepares his most sensational stroke of all — a burlesque of one of the most solemn and famous of Gregorian chants, the Dies irae (Day of Wrath). This chant is the centerpiece of Masses for the Dead, or Requiem Masses; in Catholic France, any audience would have recognized the Dies irae instantly. Three segments of it are used; each is stated first in low brasses, then faster in higher brasses, then, faster still and in the vulgar spirit of the transformed idée fixe, in woodwinds and plucked strings. It makes for a blasphemous, shocking picture of the witches’ black Mass.

The final section of the movement is the “Witches’ Round Dance.” Berlioz wrote a free fugue — a traditional form in a nontraditional context; he uses counterpoint to give a feeling of tumult and orgiastic confusion. The subject is an excited one:

The climax of the fugue (and of the symphony) comes when the round dance theme is heard together with the Dies irae, played by the trumpets. Berlioz wanted to drive home the point that it is the witches, represented by the theme of their round dance, who are parodying the church melody. The idée fixe seems at last to be forgotten.

But in real life Berlioz did not forget; he married Smithson and both of them lived to regret it.