Modest Musorgsky, Pictures at an Exhibition (1874)

The title of this interesting work refers to a memorial exhibit of pictures by a friend of Musorgsky’s who had recently died, the Russian painter Viktor Hartmann. Like Musorgsky, Hartmann cared deeply about getting Russian themes into his work. Pictures at an Exhibition was originally written for piano solo, as a series of piano miniatures joined in a set, like Robert Schumann’s Carnaval (see page 244). In 1922 the set was orchestrated by the French composer Maurice Ravel, and this is the form in which it is usually heard.

Promenade [1] To provide some overall thread or unity to a set of ten different musical pieces, Musorgsky hit upon a plan that is as simple and effective as it is ingenious. The first number, “Promenade,” does not refer to a picture, but depicts the composer strolling around the picture gallery. The same music returns several times in free variations, to show the promenader’s changes of mood as he contemplates Hartmann’s varied works.

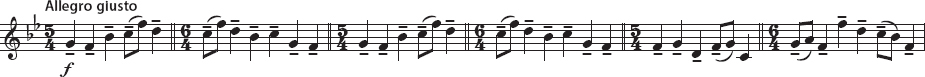

The Promenade theme recalls a Russian folk song:

Ravel orchestrated this forceful theme first for brass instruments, later for woodwinds and strings. Quintuple meter (5/4: measures 1, 3, and 5) is a distinct rarity, and having this meter alternate with 6/4 (measures 2, 4, and 6) rarer still. The metrical oddity, in respect to usual classical procedures, gives the impression of folk music — and perhaps also of walking back and forth without any particular destination, as one does in a gallery.

Gnomus “Gnomus” is a drawing of a Russian folk-

The lurching rhythms and dissonance of “Gnomus” and the 5/4 meter of “Promenade” are among the features of Musorgsky’s music that break with the norms of mainstream European art music, in a self-

Promenade [2] Quieter now, the promenade music suggests that the spectator is musing as he moves along . . . and we can exercise our stroller’s prerogative and skip past a number of Hartmann’s pictures, which are not nationalistic in a Russian sense. Some refer to other peoples, and Musorgsky follows suit, writing music we would call exotic: “Bydlo,” which is the name of a Polish cattle-

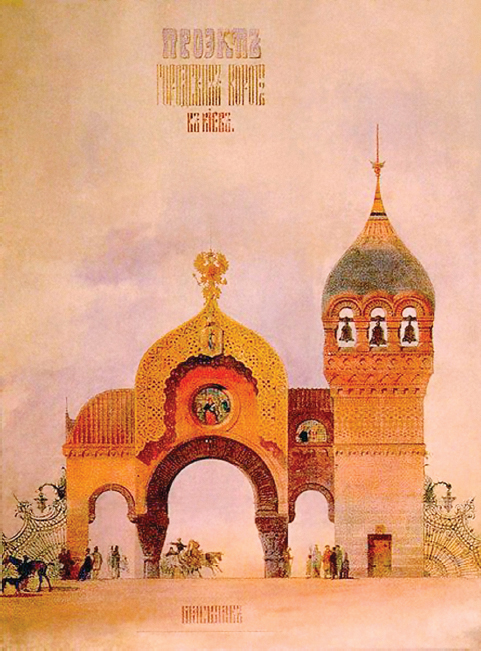

The Great Gate at Kiev The last and longest number is also the climactic one. It illustrates — or, rather, spins a fantasy inspired by — a fabulous architectural design by Hartmann that was never executed.

Musorgsky summons up in the imagination a solemn procession with crashing cymbals, clanging bells, and chanting Russian priests. The Promenade theme is now at last incorporated into one of the musical pictures; the promenader himself has become a part of it and joins the parade. In addition, two real Russian melodies appear:

The ending is very grandiose, for grandiosity forms an integral part of the national self-