Global Perspectives

Musical Drama Worldwide

We saw earlier (page 57) that most religious traditions make substantial use of singing of one sort or another. Likewise, most traditions of drama worldwide do not consist of plain speech and little else, but instead incorporate chanting, singing, instrumental music, and dance. In this way they resemble the European opera we have studied and other kinds of Western drama, from ancient Greek tragedy and comedy to today’s megamusicals on Broadway.

Perhaps, in fact, this connection between music and drama is related at a very deep level to the connection between singing and religion. Just as the heightening of prayer in song seems to give readier access to invisible divinity, so music seems somehow compatible with the illusory, real-

Whatever the reason, from the ancient beginnings of drama down to the present day, music has been joined with acting more often than not.

Asia has developed particularly rich traditions of musical drama. These include the shadow plays of Indonesia, accompanied by gamelan music and relating stories from lengthy epic poems by means of the shadows of puppets cast on a screen (see page 199). In India, religious dance-

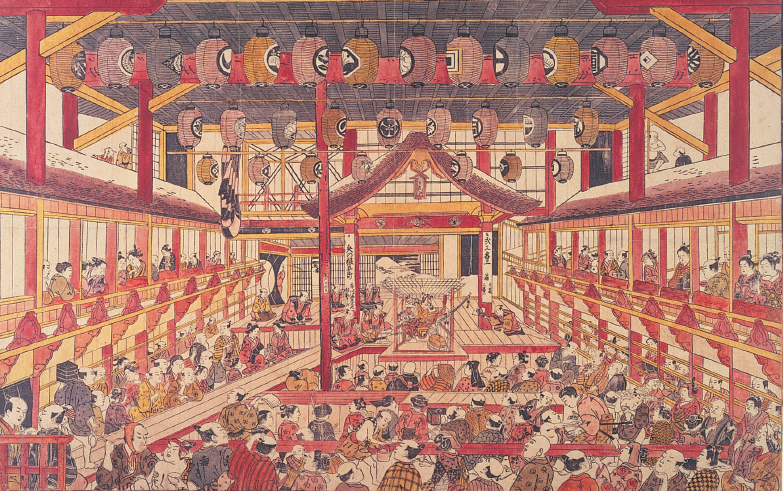

In Japan, meanwhile, several types of musical drama have arisen over the centuries. One of the most important, kabuki (kah-

Chinese Opera

What we know as Beijing opera, the most famous variety of Chinese musical drama, is in China called jingju (chéeng-

Beijing opera is a relatively recent product of a long, complex history. Some of its stylistic features were introduced to the capital by provincial theater troupes at the end of the eighteenth century, while others developed through much of the nineteenth century. Only by the late 1800s did Beijing opera assume the form we know today, and even that form has more recently undergone striking changes, especially during the Communist period of the last sixty-

Voice Types in Beijing Opera In European opera, different voice types have been habitually associated with specific character types. In Romantic opera, tenors usually play young, vital, and amorous characters (for example, the Duke in Verdi’s Rigoletto), and sopranos play their female counterparts (Gilda). Low male voices, baritone and bass, can variously have comic, evil, or fatherly associations (Rigoletto).

Such conventional connections of voice and character type are highly developed in Beijing opera, too — but the voice types are different. Young men of romantic, dreamy inclination sing in a high register and usually in falsetto. Older, bearded men, trusted and loyal advisers of one sort or another, sing in the high baritone range. Warriors sing with a forced, throaty voice; in addition they must be skilled acrobats in order to enact lively, athletic battle scenes.

Two other special male roles are the male comic, who speaks more than he sings, and the jing, or face-

The female roles in Beijing opera were, until the Communist era, almost always sung by male impersonators. They include a mature, virtuous woman, sung in a refined, delicate falsetto (when women sing these roles today, they imitate that male falsetto). A younger woman, lively and flirtatious, is sung in a suggestive, innuendo-

The Orchestra The small orchestra of Beijing opera consists of a group of drums, gongs, and cymbals, a few wind instruments, and a group of bowed and plucked stringed instruments. These are all played by a handful of versatile musicians who switch from one instrument to another during the performance.

The percussion group is associated especially with martial music, accompanying battle scenes. But it also fulfills many other roles: It can introduce scenes, provide special sound effects, use conventional drum patterns to announce the entrances and social status of different characters, and play along with the frequent songs. The most important function of the stringed instruments is to introduce and accompany the songs.

Beijing Opera Songs In a way that is somewhat akin to the Western contrast of recitative and aria, Beijing opera shows a wide range of vocal styles, from full-

The Prince Who Changed into a Cat

Our recording presents the beginning of a scene from The Prince Who Changed into a Cat, one of the most famous of Beijing operas. The story concerns an Empress who is banished from Beijing through the machinations of one of the Emperor’s other wives. (Her newborn son, the Prince of the title, is stolen from his cradle and replaced by a cat.) The present scene takes place many years later, when a wise and just Prime Minister meets the Empress and determines to restore her to her rightful position.

First the percussion plays, and then stringed instruments, along with a wooden clapper, introduce an aria sung by the Prime Minister (0:25). There are only three stringed instruments: a high-

Finally, the singer enters (0:41). He sings the same melody as the stringed instruments, though he pauses frequently while they continue uninterrupted. This heterophonic texture is typical of Beijing opera arias. The Prime Minister is a bearded old-