3 | Expressionism

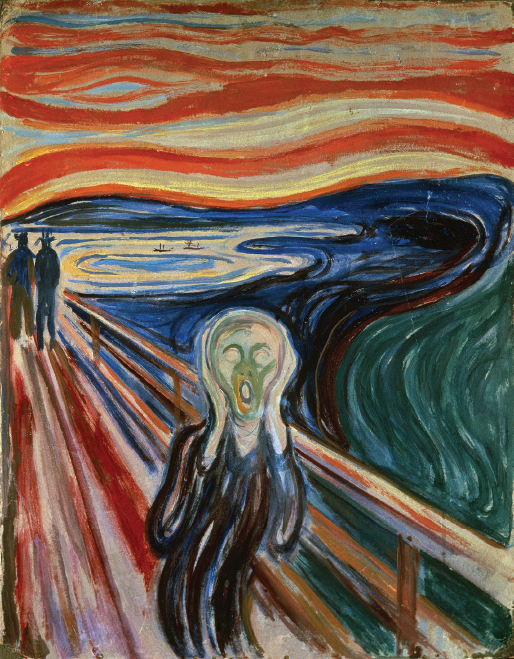

Even as Stravinsky was rejecting Romantic sentiment, in Austria and Germany composers pressed forward with music that was increasingly emotional and complex. As though intent on taking Romantic fervor to its ultimate conclusion, they found themselves exploiting extreme states, extending all the way to hysteria, nightmare, even insanity. This movement, known as expressionism, shares its name with important parallel movements in art and literature (see page 308).

These years before World War I also saw the publication of the first works of Sigmund Freud, with their new analysis of the power of unconscious drives, the significance of dreams, and the central role of sexuality. Psychoanalytic theory had a clear impact on German expressionism; a vivid example is Erwartung (Anticipation), a monologue for soprano and orchestra written by Arnold Schoenberg in 1909. In it, a woman comes to meet her lover in a dark wood and spills out all her terrors, shrieking as she stumbles upon a dead body she believes to be his. One cannot tell whether Erwartung represents an actual scene of hysteria, an allegory, or a Freudian dream fantasy.

Schoenberg was the leading expressionist in music. He pioneered in the “emancipation of dissonance” and the breakdown of tonality, and shortly after World War I he developed the revolutionary technique of serialism (see page 327). Even before the war, Schoenberg attracted two brilliant Viennese students who were only about ten years his junior and who shared almost equally in his innovations. Schoenberg, Anton Webern, and Alban Berg are often referred to as the Second Viennese School, by analogy with the earlier Viennese trio of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven.