Trends 1980–2000: Punk, Rap, and Post-Rock

Despite — or perhaps because of — this commercialization, rock survived. There were strong new currents countering commercialization and corporate control. Indeed the last decades of the twentieth century brought something of a rejuvenation. Three trends in particular can be pointed to:

- The youthful disaffection that set in by the end of the 1960s, as the idealistic counterculture began to sense its impotence, hardened in the next decade. Its most influential expression was the nihilistic alienation of punk rock. In New York City and Britain, groups like the Patti Smith Group (“Gloria”), the Ramones (“Blitzkrieg Bop”), and the Sex Pistols (“Anarchy in the UK”) reacted against the commercial flashiness of much rock with what we might call an anti-

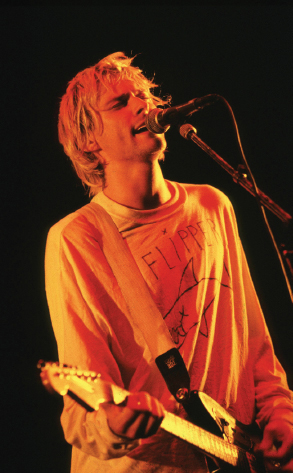

aesthetic: All expression was possible, including no expression. All musical expertise was acceptable, including none. (Some of the punks were fully aware that in this move they were following the lead of avant- garde modernists like John Cage; see page 367.) The punk approach gave strong impetus to a kind of populist movement in rock, encouraging the formation of countless “garage bands” and the 1990s’ indie rock, distributed on small, independent labels. Some punk singers also pioneered an alienated, flat vocal delivery that contrasts both with the impassioned singing of earlier rock and with the streetwise cool of rap. In these features punk looked forward to the unpolished, moving, but somehow distant style of grunge rock, led by Kurt Cobain (until his death in 1994) and his band Nirvana.

Kurt Cobain. Gie Knaeps/LFI/Photoshot.

Kurt Cobain. Gie Knaeps/LFI/Photoshot. - First emerging about the same time as punk, hip-

hop or rap has compiled a substantial history as a primary black rhetorical and musical mode. Early on, its influence was transmitted, with stunning postmodern quickness, around the globe. Already by 2000 rap had become a strong current in world pop-music traditions, its influence heard in the vocal delivery of countless rock and pop groups. The early 1990s marked rap’s moment of highest notoriety in the American mass media. One strain of rap — the violent, misogynist variety known as gangsta rap — figured centrally in the public debate, which was marked not only by justifiable distaste at the vision of these rappers but also by unmistakable racist undertones. However, the debate tended to miss two important points: First, while rap originated as a pointed expression of black urban concerns, it was marketed successfully to affluent whites, especially suburban teens. Second, the clamor against gangsta rap ignored the wider expressive vistas of rap as a whole. Already in 1980 rap was broad enough to embrace the hip-

hop dance numbers of the Sugarhill Gang (“Rapper’s Delight”) and the trenchant social commentary of Grandmaster Flash (“The Message”). By the 1990s, rap could range from the black empowerment messages of Public Enemy (“Don’t Believe the Hype”) to Queen Latifah’s assertions of women’s dignity and strength (“Latifah’s Had It Up 2 Here”). - Around 1990 a new, experimental rock movement began to take shape; soon it was dubbed post-

rock. Early post-rock groups (for example, Slint; “Good Morning Captain”) emerged from the indie rock movement. They typically employed rock instrumentation and technology in a style that features hypnotically repeated gestures (especially bass ostinatos), juxtaposition of contrasting plateaus of sound, slow transitions and buildups, free improvisation, and emphasis of instruments rather than voice. (When a voice is present, it often doesn’t so much sing as recite fragments of poetry in front of the instrumental backdrop.) This thumbnail sketch alone is enough to reveal post- rock’s relation to two other musical movements we have encountered: minimalism (see page 369) and fusion jazz (see page 396).

And just as classic jazz appeared by the 1970s, so today we have classic rock; and the same question might again arise: Can creative freshness survive the prepackaged recycling of rock styles and gestures?

But perhaps, in the end, this is the wrong way to think of rock in the twenty-