3 | Music as Expression

In parts of Josquin’s Pange lingua Mass, as we have just seen, the music does not merely enhance the liturgy in a general way, but seems to address specific phrases of the Mass text and the sentiments behind them. Music can be said to “illustrate” certain words and to “express” certain feelings. The exploration of music’s power to express human feelings was a precious contribution by musicians to the Renaissance “discovery of the world and of man.”

Renaissance composers derived inspiration for their exploration of music’s expressive powers from reports of the music of ancient Greece, just as artists, architects, and writers of the time were also looking to ancient Greece and Rome for inspiration. Philosophers such as Plato had testified that music was capable of arousing emotions in a very powerful way. In the Bible, when Saul is troubled by an evil spirit, David cures him by playing on his harp; there are similar stories in Greek myth and Greek history.

How modern music could recapture its ancient powers was much discussed by music theorists after the time of Josquin. They realized that both music and words could express emotions, and they sought to match up the means by which they did so. Composers shared this expressive aim of matching words and music; in fact, devotion to the ideal of musical expression, by way of a text, was one of the main guiding ideas for musicians of the later Renaissance. This led to two important new developments in the music of the time:

- First, composers wanted the words of their compositions to be clearly heard. They strove for accurate declamation— that is, they made sure that words were sung to rhythms and melodies that approximated normal speech.

This may seem elementary and obvious, but it is simply not true of most medieval polyphony (or of many plainchants). The Renaissance was the first era when words were set to music naturally, clearly, and vividly.

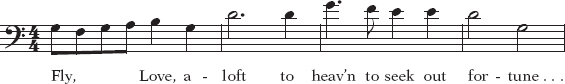

- Second, composers began matching their music to the meaning of the words that were being set. The phrase word painting is used for this musical illustration of the text. Words such as fly and glitter were set to rapid notes, up and heaven to high ones, and so on:

Sigh was typically set by a motive including a rest, as though the singers have been interrupted by sighing. Grief, cruel, torment, harsh, and exclamations such as alas — words found all the time in the language of Renaissance love poetry — prompted composers to write dissonant or distorted harmony. First used extensively in the sixteenth century, word painting has remained an important expressive resource of vocal music. For examples from the Baroque period, when it was especially important, see pages 86, 88, 143, and 147.