Texture: Basso Continuo

Some early Baroque music is homophonic and some is polyphonic, but both textures are enriched by a feature unique to the period, the basso continuo.

In Baroque music the bass line is performed by bass voices (as in Renaissance music) or low instruments such as cellos or bassoons. But the bass part in Baroque music is also played by an organ, harpsichord, or other chord instrument. This instrument not only reinforces the bass line but also adds chords continuously to go with it. The basso continuo, as it was called, meaning “continuous bass,” has the double effect of clarifying the harmony and making the texture bind or jell. Baroque music players today usually call it simply the continuo.

One can see how the continuo responds to the growing reliance of Baroque music on harmony (already clear from Gabrieli’s motet). Originally, the continuo was simply the bass line of the polyphony reinforced by chords; but later the continuo with its chords was mapped out first, and the polyphony above adjusted to it. Baroque polyphony, in other words, has systematic harmonic underpinnings.

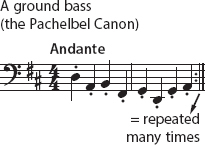

This fact is dramatized by a musical form that is characteristically Baroque, the ground bass. This is music constructed from the bottom up. In ground-

Baroque ground-

Another name for the ground bass comes from Italian musicians of the Baroque: basso ostinato, meaning “persistent” or “obstinate” bass. By extension, the term ostinato is also used to refer to any short musical gesture repeated over and over again, in the bass or anywhere else, especially one used as a building block for a piece of music. Ostinatos are found in most of the world’s musical traditions (see page 94).