Primary Cilia Are Sensory Organelles on Interphase Cells

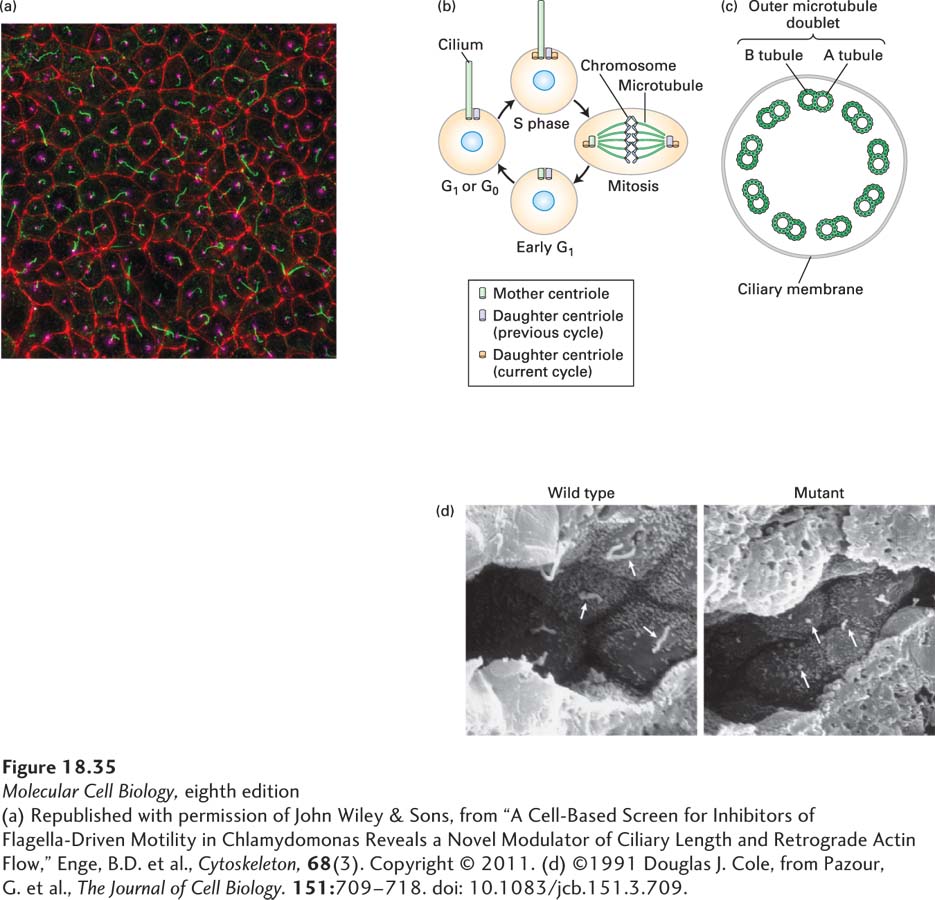

Many vertebrate cells bear a solitary nonmotile cilium known as the primary cilium. The primary cilium is a stable structure that is resistant to drugs such as colchicine that disassemble most microtubules; after colchicine treatment, the only remaining microtubules are found in the centrioles and the primary cilium (see Figure 18-12). Moreover, the tubulin in the primary cilium is highly acetylated, so using antibodies that specifically recognize acetylated α-tubulin readily identifies the single primary cilium on each interphase cell (Figure 18-35a).

Terminally differentiated cells and dividing cells in interphase contain primary cilia. In the latter case, the presence of the primary cilium is tied to the duplication cycle of the centrioles (discussed in Section 18.6), with the older, “mother” centriole functioning as the basal body for the assembly of the primary cilium (Figure 18-35b).

Page 848

The primary cilium is nonmotile because it lacks the central pair of microtubules and the dynein arms that are found in other cilia and in flagella (Figure 18-35c). Recent work has led to the discovery that the primary cilium is instead a sensory organelle, acting as the cell’s “antenna” by detecting extracellular signals. For example, the sense of smell is due to binding of odorants by receptors located in the primary cilia of olfactory sensory neurons in the nose (see Chapter 22). In another example, the rod and cone cells of the eye have a primary cilium with a greatly expanded tip to accommodate the proteins involved in photoreception. The retinal protein opsin moves through the primary cilium at about 2000 molecules per minute, transported by kinesin-

The primary cilium has a diffusion barrier at its base so that only the appropriate proteins can enter it: globular proteins of 10 kDa have ready access, but proteins above 40 kDa are excluded. Remarkably, transport through this barrier has similarities to transport into the nucleus through nuclear pores, and indeed, these two forms of transport have some components in common. Recall that import though nuclear pores requires a gradient of the Ran GTPase and involves binding of cargo proteins to importins (see Section 13.6). Transport of at least some proteins, such as kinesin-